Legislators and descendants of Robert E. Lee and the families he enslaved want to drop the Confederate general from the formal name of the manor house at Arlington National Cemetery.

When Stephen Hammond was in his early teens, a cousin asked him if he knew he was descended from the first family of the United States. “As a Black kid in Denver, I said to myself ‘Get outta here! No way,’” recalled Hammond, an interpretive volunteer at Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial in Virginia and a trustee for the Arlington House Foundation. The conversation sparked a lifelong curiosity — a responsibility, as he puts it — to sort through fact, fiction and folklore to learn more about his family and where they came from.

Hammond’s genealogical journey revealed a slightly different lineage than his cousin’s, but a close relationship to George and Martha Washington, nonetheless.

Hammond is a descendent of Nancy Syphax, an enslaved Black woman at Washington, D.C.,’s historic Decatur House whose brother Charles was enslaved as a house servant at nearby Arlington House Plantation. Charles Syphax previously was enslaved at Mount Vernon by Martha Washington, who died when he was about 10 years old.

After Martha Washington’s death in 1802, her grandson from her first marriage, George Washington Parke Custis, inherited land and people. He moved 57 enslaved people, including Charles Syphax, to the property that would become Arlington House Plantation.

Custis, who was white, fathered a child with an enslaved Black woman, Arianna Carter, in 1803. Their child, Maria, later served as the personal maid to her younger half-sister, Custis’ white daughter, Mary. In 1821, Maria was allowed to marry Charles Syphax in the parlor of Arlington House — the same room where Mary married Robert E. Lee in 1831.

For generations, visitors to Arlington House didn’t hear the stories of Charles and Maria Syphax and other enslaved African Americans, such as housekeeper Selina Gray, who was entrusted with the keys to Arlington House when the Lees fled during the Civil War.

During a three-year, multi-million dollar rehabilitation to the park site, however, the National Park Service connected with six enslaved African American families, restored and acquired new artifacts, and made an unexpected archaeological discovery in the slave quarters. As a result, visitors to Arlington House since its June 2021 reopening see new exhibits about the lives of African Americans on the property and are introduced to a more complete history of the 19th-century house, its people and the impacts of slavery.

A sideview of Arlington House, with graves in the foreground.

NPS“Many visitors are grateful to see the site open, and they appreciate the National Park Service’s accurate and inclusive approach,” said Charles Cuvelier, superintendent of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, which oversees Arlington House. “In general, the team receives more written inquiries asking the NPS to broaden the interpretation even more. We think this supports our efforts to tell the whole story.”

As part of this broader storytelling, Hammond and other descendants — including those of the Lee family — and current members of Congress want the national park site’s name changed and redesignated as Arlington House National Historical Site. Removing Lee’s name, they said, would make the site more inclusive and further recognize the intertwined lives of the estate’s white and Black families. A redesignation also would strengthen the site as a focal point for education, awareness and healing, they said.

Two joint resolutions calling for the name change were introduced in Congress in July 2022 by Rep. Don Beyer and Sen. Tim Kaine, both of Virginia. More than 1,250 people from across the country have signed an online petition supporting their efforts. Philanthropist David Rubenstein, who donated $12.35 million to the Park Service for the Arlington House rehabilitation, called for the name change through a Washington Post opinion piece in 2020.

Philanthropist David Rubenstein, left, with Syphax family descdendant Stephen Hammond at Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial in 2021.

Courtesy of Stephen HammondThis fall, The Washington Post published an op-ed by Hammond and Lee descendant Lee Crittenberger Hart in support of the name change, in which they wrote, “Our families realize that the name ‘The Robert E. Lee Memorial’ focuses solely on one side of those who lived at Arlington House and excludes and diminishes the lives and histories of those who were enslaved. … There are important aspects of the Arlington House history that, until recently, have been either understated or omitted from the overall interpretation at the site. It is time to include all sides of the history of Arlington House.”

NPCA strongly supports the park site’s name change and redesignation as a national historic site.

“Keeping the Lee name for this federally owned property is problematic because Robert E. Lee owned and sold enslaved people, helping to enhance his financial circumstances, and then he resigned his military commission to fight for an armed insurrectionist group,” said Alan Spears, NPCA’s senior director of cultural resources.

“Ultimately though, this effort is about creating a redesignation that will help to open the site to more accurate and just interpretation of the history of the enslaved people who labored at Arlington House and the people who owned them.”

Here are frequently asked questions about the issue.

Who built the mansion?

Arlington House was built between 1802 and 1818 by enslaved Blacks at the direction of first lady Martha Washington’s grandson, Lt. George Washington Parke Custis. He intended the home to be a memorial to his step-grandfather George Washington, where he could display his collection of memorabilia of the first U.S. president.

Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial.

Dreamstime.comThe Greek Revival structure’s design is attributed to George Hadfield, who earlier had worked on the U.S. Capitol building. Enslaved people cleared and leveled the building site, harvested the timber for Arlington House’s floors and supports, and made by hand the building’s bricks that they later covered with cement in a faux finish process to resemble marble and sandstone. They also built the mansion’s accompanying slave quarters.

How did Robert E. Lee enter the Custis family?

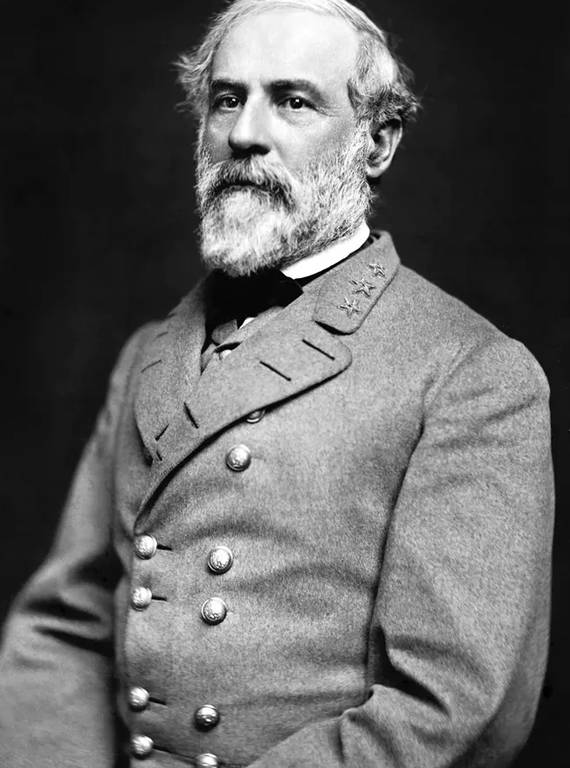

Gen. Robert E. Lee in 1864.

NPSCustis’ daughter, Mary Anna Randolph Custis, and Robert E. Lee knew one another as children. They married in the Arlington House parlor in 1831. The couple and their children resided there for 30 years, even though Lee’s U.S. Army career kept him away much of the time. When his father-in-law died in 1857, Lee was executor of the will and took over management of the property and people — a job he continued until the family fled the home at the start of the Civil War.

Is Robert E. Lee being removed from historical interpretation?

No. The inclusive site continues to tell the story of Lee and his family but in the larger context of this time in American history — including its racial hierarchy.

How many enslaved people were at Arlington House?

Nearly 100 enslaved African Americans lived and labored on the 1,100-acre estate in the 1800s before the Civil War, maintaining the house and working the corn and wheat fields. The first enslaved people arrived with Custis, who inherited them from his grandmother, Martha Washington. He inherited more enslaved people after Martha Washington’s death at Mount Vernon in 1802 and purchased more, too.

Custis’ will when he died in October 1857 indicated all slaves should be freed within five years, yet several of them attested to Custis telling them they would be freed immediately upon his death. Lee, as executor, determined the estate was in too much financial trouble to let them go. To help pay off the estate’s debts, Lee forced the enslaved people to grow additional crops and also hired some out to other plantations. He finally freed them in December 1862.

Some enslaved people were emancipated in the 1820s at the urging of Custis’s wife, who also had been tutoring them in basic reading and writing — a practice continued by her daughter Mary Lee, despite Virginia law prohibiting the education of enslaved people. A few of these emancipated families remained on the property.

An exhibit in the slave quarters at Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial.

NPSCustis sold his enslaved daughter Maria Carter Syphax and her first two children to Edward Stabler, a Quaker in Alexandria, who may have later freed her. She lived with her still-enslaved husband Charles on a 17-acre plot given to her by Custis. Others, such as William and Rosabella Burke, immigrated to Africa with their four children.

Did enslaved people leave Arlington House during the Civil War?

No. Even after the Lee family evacuated in May 1861 and U.S. Army occupied the property, many freed individuals stayed on the estate. Among them was Selina Gray, a second-generation enslaved person and personal maid to Lee’s wife.

Enslaved housekeeper Selina Gray at Arlington House, with her daughters, during the Civil War era.

NPSMary Lee entrusted Gray with the household keys as her family evacuated, giving Gray responsibility for all the family’s possessions, including the George Washington artifacts.

Gray and her husband, Thornton, lived on the estate for many years, and their daughters were instrumental in the restoration of Arlington House in the 1920s and 1930s.

A Freedman’s Village operated on the estate from 1863 to 1900, about a half-mile south of the mansion. It was intended to be a model community where the formerly enslaved could learn trades to become self-sufficient elsewhere. The population quickly swelled from 100 to several thousand, however, and most of the residents stayed in the community to work government-owned farms nearby.

Why is Arlington House located in a cemetery?

The house was the anchor of the large Arlington Plantation until the Civil War when the U.S. Army seized the home in 1861. By 1864, Union soldiers had begun burying their dead on the property as cemeteries in Washington and surrounding areas filled up.

Arlington National Cemetery

© Sandra Manske | Dreamstime.comThe U.S. government purchased the seized property in 1864, the same year Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton instructed that part of the Arlington estate be surveyed and laid out for a national cemetery. Bodies were intentionally placed near the house to make living there undesirable. At the time, this included 15,000 Civil War dead on the grounds, plus a tomb for the remains of 2,111 unknown soldiers placed in the mansion’s rose garden.

Today, more than 400,000 people are buried at Arlington National Cemetery. Among them is James Parks, who was born into slavery on the property — the only person laid to rest in Arlington Cemetery who was born on the old plantation. Parks dug military graves there after his freedom and was buried with full military honors in 1929.

When was Robert E. Lee’s name added to Arlington House?

Congress and President Calvin Coolidge designated Arlington House as a national memorial to Robert E. Lee in 1925 to honor his role in promoting peace and reunion after the Civil War. By then, Lee had earned respect from the North and South for his reconciliation efforts. Thirty years later, a joint resolution of Congress in 1955 designated the home as the Custis-Lee Mansion.

In 1972, Congress passed a law changing the name to Arlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial. Today, the park site is considered a place for study and contemplation of some of America’s most challenging — and often contradictory — history, which Lee embodied: military service, sacrifice, citizenship, duty, loyalty, slavery and freedom.

What did the rehabilitation of Arlington House between 2018 and 2021 entail?

The rehabilitation included stabilization of the home’s foundation, restoration of interior and exterior finishes, repairs to windows and doors, and improved accessibility, among other physical improvements.

The parlor of Arlington House.

NPSElectrical work, lighting, security, climate management and fire suppression systems were also improved. Some repairs were needed as a result of a 2011 earthquake.

In addition, Park Service curators worked to conserve or restore more than 1,000 historic objects and acquired 1,300 antiques or reproductions, including several artifacts associated with African American history.

An exhibit in the south slave quarters at Arlington House with Maria Syphax’s pitcher.

NPSNew research allowed the Park Service to interpret the Custis and Lee family history alongside that of more than 100 enslaved people. The north slave quarters, which previously housed the park site’s bookstore, is now exhibit space. It features a memorial wall with the names of those who built and contributed to the Arlington House plantation.

Have there been recent archaeological discoveries at the site?

Yes. In 2021, construction crews working in the mansion’s south-end slave quarters unearthed a 20th-century reconstructed brick flooring. Digging past the modern fill dirt, they found four glass bottles clustered in soil from the mid-1800s. Park archaeologists determined the spot to be a subfloor storage pit used by Selina Gray and her family, perhaps as a magical or religious shrine.

Four glass bottles found in a subfloor storage pit in the slave quarters of Arlington House in 2021, believed to be used by enslaved people as a magical or religious shrine.

NPSThe Park Service said the four bottles are thought to be part of a “spirit bundle” and may indicate West African religious connections or folk magic customs at Arlington House. The bottles were placed side by side pointing northward, as if toward freedom. The finding suggests the enslaved people at Arlington House resisted their bondage and persevered for freedom.

How is the National Park Service helping people reflect on Arlington House’s history of slavery?

In addition to the new exhibits, the park site in August began offering twice-daily ranger-led talks on topics of Black history, perspective and contemporary connections, as well as the life and legacy of Robert E. Lee and how he has been memorialized.

U.S. Army soldiers on the steps of Arlington House in 1862, during the Union occupation of the home.

Library of CongressEach program allows guests to dig deeper into the site’s stories and reflect, process and share perspectives with each other.

The park’s leadership also redesigned an interpretive volunteer program, of which Stephen Hammond is a member. Volunteer docents connect with visitors, share stories and help people process the site’s hard questions and topics.

Can the Park Service change the Arlington House name?

No. The Park Service does not have the authority to change the name of the park site to Arlington National Historical Site, as family members and lawmakers are proposing. Congress established the current name and, therefore, is the only entity with authority to change it again.

Take a virtual tour of Arlington House

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

About the author

-

Linda Coutant Staff Writer

Linda Coutant Staff WriterAs staff writer on the Communications team, Linda Coutant manages the Park Advocate blog and coordinates the monthly Park Notes e-newsletter distributed to NPCA’s members and supporters.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Mid-Atlantic

-

Issues