Colorado’s Fort Garland Museum in the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area reveals the converging stories of Hispanic, Native American and African American cultures in the 19th century.

A sea of silvery native shrubs and potato fields stretch across southern Colorado’s vast San Luis Valley. To the west lies the headwaters of the Rio Grande, where craggy rhyolite canyons hint of a turbulent volcanic past. To the east, the 14,000-foot peaks of the Sangre de Cristo range cradle Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. Throughout, wild horses, crumbling adobe churches and sandhill cranes dot the landscape.

The valley is home to deep-rooted culture and history, particularly at the intersection of Hispanic, Native American and African American heritage. That’s one of the reasons the region was designated as a national heritage area — the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area — in 2009.

“The valley is an interesting and unexpected convergence of people who have had to learn how to live with each other,” said Eric Carpio, director of the Fort Garland Museum and Cultural Center, which is among nearby attractions the National Park Service suggests to Great Sand Dunes visitors. “Sometimes it has resulted in remarkable collaborations, and other times with violence and trauma. But for a long time, much of its history was swept under the rug.”

So, for the last few years, Carpio and his staff have made bold and elegant moves to better share some of the valley’s complicated legacies. To fully grasp the magnitude of what they’ve done, it’s necessary to first know a bit about the valley’s history.

People have lived in the region since at least the time of the mammoths. Navajo, Ute, Apache, Kiowa and Comanche all called it home. After the Spanish arrived in 1598, the Hispanic population gradually grew to prominence. Then in 1848, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hildago ceded the San Luis Valley and much of the West from Mexico to the United States. Residents suddenly found themselves living in U.S. territory, and many lost their property when their land grants were revoked.

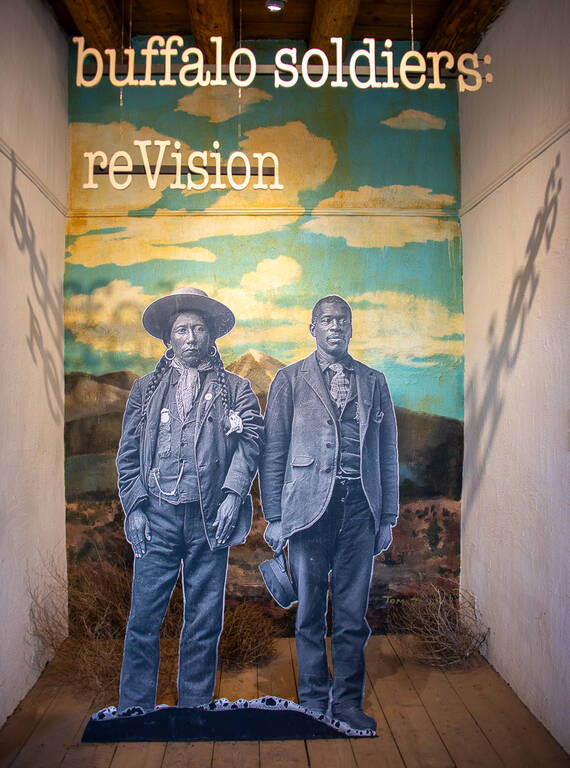

Signage for Fort Garland Museum’s “buffalo soldiers: reVision” exhibit, which runs through 2025.

©Steve AlbertsBy 1858, Fort Garland was built to protect Manifest Destiny, the philosophy that the United States had a divine mission to expand westward into what it inaccurately touted as virgin lands and create a transcontinental nation.

After the Civil War, the all-Black 9th Calvary became stationed at the fort. They were dubbed the Buffalo Soldiers by Comanches and Cheyennes — one possible reason, historians believe, was due to their physical fortitude and hair, which the Native Americans generally perceived to be curly. Tasked with protecting white settlers, the Buffalo Soldiers often had the unenviable duty of being on the front lines of Native American removal. They were well-respected by the U.S. government for their valiant and honorable service, and they often established friendships with Native Americans.

“Here in the valley, we are at the intersection of several Indigenous homelands, the northernmost edge of Spanish and Mexican settlement, and American westward expansion,” Carpio said. “Ultimately, this region was shaped by how those relationships evolved. It’s a wildly complex history which still directly impacts how people live their lives today.”

So, how did a rural, small-town museum go about unraveling such an intricate, nuanced puzzle?

The first step was dismantling the 69-year-old centerpiece of the fort-turned-museum: a life-size mannequin of Kit Carson, an American brigadier general perhaps best known for his merciless campaign against the Diné people (also known as Navajo).

The museum then began collaborating with Tribal partners and artist Chip Thomas, an African American physician who worked on the Navajo Nation for 35 years. In June 2021, the exhibit “Unsilenced: Indigenous Enslavement in Southern Colorado” officially took Carson’s place, in the very rooms of the fort that were likely his historical living quarters.

The exhibit includes two room-sized translucent cloths, each with a page from an 1865 document printed on them. The title reads “List of Indian Captives Acquired by Purchase,” and underneath are the names of enslaved people, with ages and Tribal affiliations. As Carpio points out, most of the Indigenous names have been changed to Western ones, as women and children were often baptized into the Catholic Church and prohibited from speaking their Native language. This led to generations of Native Americans who had lost all connection to their cultural traditions and Tribal heritage, including a Navajo boy who Carson kept enslaved.

Though those practices ended 150 years ago, the reverberations of that detachment are still affecting the community. “A lot of families have come forward and told us they had heard their ancestors were enslaved but doubted the story because no one ever heard about Native American enslavement,” Carpio said. “Now families have felt validated that there’s truth to the stories their parents and grandparents told.”

One visitor even found his ancestor’s name in the documents. “The emotion that’s suddenly unleashed from that, the pain and anger of their heritage stripped away, there’s a lot of history we have to unpack,” Carpio said. “That’s what we’re trying to reconcile. Sharing these powerful images hopefully starts a dialogue.”

In 2022, the museum expanded its efforts by hosting the temporary exhibit “Merciless Indian Savages,” in which Pyramid Lake Paiute artist Gregg Deal interpreted what American Democracy means in Indian Country. Then this summer, “buffalo soldiers: reVision” opened as a collection of works by eight artists. The exhibit runs through 2025.

“How did formerly enslaved peoples rationalize the subjugation of another race, and in what ways do Buffalo Soldiers connect with the lands they were helping to take away from Indigenous people?” asked Thomas, in an artist’s statement. “The land provided solace and space for contemplation, maturation and dreaming of new possibilities in a way the black soldier couldn’t consider in the Reconstruction South.”

Telling stories such as these through contemporary art is an unusual choice for a history museum, but Carpio says the approach has started a lot of meaningful dialogue. “Particularly in communities of color, artists are the knowledge keepers,” he said. “Plus, artists have a good way of not hitting you over the head with it, opening new perspectives without being condemning.”

Earlier this year, the museum earned a finalist spot in the National Medal for Museum and Library Science, and visitors often tell Carpio that it’s a more welcoming and relevant space to them now than it was before. After viewing the exhibits, one couple even asked Carpio how they could better honor the Buffalo Soldiers and Native Americans who once lived in the valley.

“That people came in and reflected on the exhibits in that way, in all of our wildest hopes and goals as a museum, that’s it,” Carpio said. “And the stories are still expanding. We have empty rooms in some of our exhibit spaces as a signal to the community there’s more to be done. The reconciliation and healing is ongoing.”

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

About the author

-

Karuna Eberl Contributor

Karuna Eberl ContributorKaruna Eberl writes about wildlife, history and adventure from the sandbars of the Florida Keys and the high country of Colorado.