A new book shares some of the fascinating history behind the young women who unknowingly helped build the first atomic bomb at what could soon become the Manhattan Project National Historical Park in Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

Editor’s note: Since NPCA posted this story, Congress officially designated the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, which includes the “Atomic City” of Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

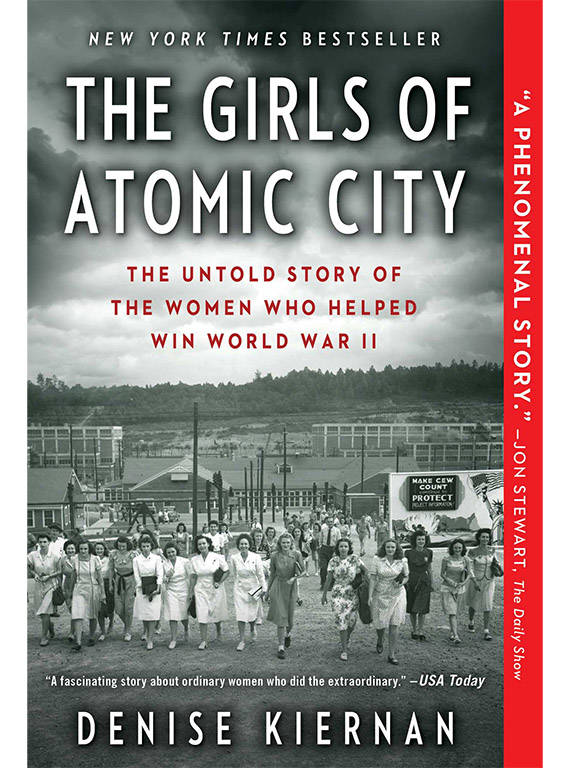

Atomic City by Denise Kiernan

If you feel out of the loop at work, you’ve got nothing on the ladies in Denise Kiernan’s new book, The Girls of Atomic City. This artfully written tale shares a new side of the mysterious history behind the making of the atomic bomb: a community of workers, primarily young women, who were unknowingly enriching uranium for the top-secret Manhattan Project.

“Atomic City” was a development in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where roughly 75,000 people worked at the height of World War II. It is also one of three sites recommended by the Park Service for inclusion in a long-awaited new national historical park that would commemorate the history of the Manhattan Project, along with sites in Los Alamos, New Mexico, and Hanford, Washington. According to Kiernan, the women at Oak Ridge were lured to this “secret city” far from their homes with promises of steady, good-paying jobs that helped the war effort—but these workers were completely unaware of the nature of the project.

I asked Denise about her book, the women she spoke with in her research, and her interest in this period in U.S. history.

Q: What inspired you to tell the story of these remarkable women?

I stumbled across a photo taken by Ed Westcott, official photographer of Oak Ridge, Tennessee, during World War II. I loved the photo, and was fascinated by the youthfulness of the women operating these enormous machines. I soon learned that those women were cubicle operators in the Y-12 plant and were working to enrich uranium for the first atomic bomb used in combat. I realized that so much of what we understand about the Manhattan Project is communicated in a very top-down manner, most often shown from the perspective of those “in the know.” I think all perspectives are valuable, especially when discussing key moments in history. I was immediately hooked and headed over to Oak Ridge to see what—and who—I could find. Luckily, many people who worked there during the war still live there today.

Q: Were these women the “Rosies” of the scientific community?

Yes and no. No, in that I did not interview anyone who did any riveting, although I did hear of and see pictures of female welders. Yes, in that the idea and legacy of a “Rosie” conjures of images of women doing what they could to help the war effort, perhaps in roles that had been, up to that point, reserved primarily for men. Not all of the women worked in scientific capacities, specifically. There were many roles available to women on the Manhattan Project: pipe inspectors, janitors, secretaries, teachers, cooks, chemists… They were a key resource in virtually every mode of employment.

Q: You share how the work force was kept completely in the dark about the nature of the work they were doing. What did they think they were working on? What motivated them to stay at their jobs if they didn’t even know what they were doing?

People’s curiosity led them to all kinds of ideas about what they might be working on. Some thought they were developing war films. Some thought they were creating a special kind of camouflage. Others, those working in a more direct scientific capacity, wondered what it might have to do with radioactivity. Many I spoke to said they didn’t know and that they didn’t care to know. All that mattered to many of the workers, male and female—and this speaks to the second part of your question—was that despite all they didn’t know, they did know that they were working on an important war project. That was enough for most people in World War II. Everyone wanted to do their part, even if doing your part meant not knowing specifically what you were doing.

Q: Is there an anecdote that struck you as particularly poignant or memorable when trying to convey what these women went through in Oak Ridge?

It’s really difficult to narrow it down to one. Everyone’s stories were so fascinating to me. In general, though, I found the women as a whole to be quite adventurous, very pioneering, in spirit. I still find it inspiring to think of an 18-year-old woman in the early 1940s going off alone, perhaps leaving her home for the first time ever, to an unknown town to do an unknown job. There are a lot of people today who would be nervous about doing something like that. I still find this particular aspect of the women’s stories remarkable.

Q: Do you think these women consider themselves patriots? Did they share mixed emotions about their roles at Oak Ridge?

All the women I interviewed were very humble and, if anything, downplayed any contribution they made during the war. To them, it was what was expected. Everyone was doing their part for the war effort, and so did they. None of them thought they should get any special recognition for that. As their role in the Manhattan Project finally became clear, these women had perhaps a larger spectrum of feelings to handle in comparison to those working outside the Manhattan Project. They were relieved, as so many were, that the war was finally over. At the same time, they were processing the knowledge that they had been a part of a world-changing and controversial moment in history.

Q: How did your experience connecting with the woman of Atomic City change your perspective on the Manhattan Project and/or women’s roles during WWII?

I have a better understanding of what a tremendous role World War II played in the lives of those who lived through it. Whether you were running scrap metal drives or working on the Manhattan Project, that war touched everyone in some way. Women played key roles in every single aspect of the war, and no matter how big or small those roles were, they all mattered. That is the primary reason I chose to focus on the experiences of young women and explore the Manhattan Project through their eyes.

Learn more about the Manhattan Project National Historical Park and the woman who was a driving force behind its creation.

About the author

-

Kati Schmidt Director, Communications, Northern Rockies, Alaska

Kati Schmidt Director, Communications, Northern Rockies, AlaskaKati Schmidt is based in Oakland, CA, and leads media outreach and communications for the Pacific, Northwest, Northern Rockies, Alaska, and Southwest regions, along with NPCA's national wildlife initiatives.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Southeast

-

Issues