Spring 2024

The Women Behind the Brotherhood

The little-known story of the wives and maids who helped propel the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to a groundbreaking agreement with the Pullman Company.

Rosina Corrothers-Tucker had spent days getting the runaround from white men in supervisory positions with the Pullman Company, and she was fed up.

It was sometime in the late 1920s, and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was on an all-court press to be recognized as a labor union by the railcar company, then the nation’s leading employer of Black workers. Corrothers-Tucker had married a Pullman porter and was so active in the Brotherhood’s efforts that when her husband was prohibited from going out on his normal train run, someone at the railyard suggested she might be to blame.

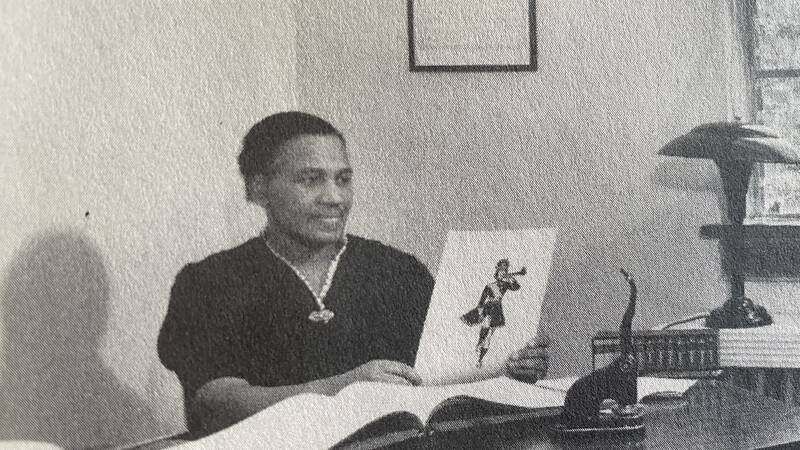

Rosina Corrothers-Tucker, pictured in her office, during her time as secretary-treasurer of the International Ladies’ Auxiliary.

COURTESY OF MELINDA CHATEAUVERTCorrothers-Tucker, described as a “firecracker” by historian Melinda Chateauvert, immediately contested Pullman’s retaliation. After being stonewalled repeatedly by a superintendent, she marched straight to his boss. “I want to tell you that nobody has anything to do with what I do!” she said, pounding on a desk in Washington, D.C.’s Union Station. “You hired my husband. You didn’t hire me!” Then, she lobbed an ultimatum: “You take care of this matter, or else I’ll be back!”

Recalling this outburst in her autobiography, she remarked: “He was so surprised he didn’t know what to do. … You know, for a black woman to speak up to a white man like that in the 1920s was extraordinary.” The executive must have thought there was a “powerful somebody” supporting her, she said, for her husband got his run back.

New Cultural Trail Proposal Will Connect More People to the Pullman Story, Its Imprint on American History

“The Pullman Cultural Trail offers opportunities to mix art and history in innovative ways that bring Pullman stories to life. This place continues to inspire all and NPCA is committed…

See more ›Corrothers-Tucker is just one woman of many who helped propel the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to success. She and other porters’ wives, along with Pullman maids, held annual conventions, conducted door-to-door canvassing, fundraised, ran local chapters and hosted dinners for visiting Brotherhood leaders. In 1935, after a decade of effort, the men — and women — prevailed: The Brotherhood became the first Black-led union to have its charter approved by the American Federation of Labor. Two years later, the workers signed an agreement with Pullman, solidifying their rights to higher pay and shorter hours.

Today, the Brotherhood’s labor rights saga is memorialized by the National A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum (founded by a woman), the Pullman National Historical Park in Chicago (currently run by women), and by countless books and videos. But finding stories about the female vanguards who smoothed the men’s path proves more difficult. Sarah Buchmeier, a park ranger and educator at the Pullman park until last August, often challenged school groups to seek out women within the park’s interpretive displays. “We don’t have much,” she said, “and when you do find women, they aren’t necessarily named.” Buchmeier attributed their absence to the park’s focus on Pullman’s 19th-century history, when women “didn’t have as big a role in the company.” Efforts are underway to better highlight the women of the Brotherhood via a new building for the museum and a potential cultural trail for the park. But the paucity of relevant historical information — which Chateauvert said is indicative of the marginalization of the activities of women, especially Black women, in the written record — remains an obstacle to greater representation in future exhibits. Even the academics who focus on the matriarchs of the Brotherhood have been able to cobble together only mere glimpses of these formidable allies.

“Their contributions have long been overshadowed by their male counterparts in the Brotherhood’s proud mythology,” wrote labor rights author Kim Kelly in her 2022 book “Fight Like Hell: The Untold Story of American Labor.” “But the truth is that the union could not have launched — or notched half of the victories it won — without their fervent support and untold hours of unpaid labor.”

TRAILBLAZERS

The roots of the Brotherhood’s struggle extend back to industrialist George Pullman and his vision for luxury rail travel. In the late 1860s, Pullman began developing kitted-out sleeper cars replete with brocade, elaborate moldings and the at-will command of porters, many of them formerly enslaved men. (As late as 1951, the primary requirement for a porter was that he be Black.) Later, select trains expanded their service to include maids, billed as “handmaidens” to the female passengers. These positions were open only to Black women until 1925 when the company began hiring a few Asian women to discourage unionizing efforts. During its heyday, nearly 30 years after Pullman’s death, the company ran 9,800 cars and employed more than 20,000 African American workers, including some 12,000 porters and perhaps 200 maids, as well as car cleaners, laundresses, busboys and railyard workers.

While working for the company afforded a certain cachet — Kelly called porters “paragons of Black manhood” — and granted employees relatively unmatched mobility, many porters felt that the perks didn’t compensate for the servile tasks or minimal pay. “People told me that it was a dog’s job,” said Milton P. Webster, longtime Brotherhood vice president and former porter, in a 1942 address to a gathering of union supporters. “Well, it wasn’t altogether a dog’s job, but it was a whole lot worse than I expected it to be.” Black train attendants made less money than white employees and were allowed less sleep, had to pay for their own uniforms and supplies, and were expected to kowtow to customers, even when harassed, denigrated or accused of theft. Many maids found their working conditions particularly isolating. Not only were they frequently the sole female on the crew, but they were also prohibited from mixing with male staff, according to Chateauvert. Maids could even be dismissed for starting a family, as Miriam Thaggert discovered while poring through company records for her book, “Riding Jane Crow: African American Women on the American Railroad.” One of the employee cards she found noted simply: “Physically unfit – pregnant.”

Frances Albrier, a nurse and Pullman maid, aided the union efforts.

SMITHSONIAN NATIONAL MUSEUM OF AFRICAN AMERICAN HISTORY AND CULTURE, FRANCES ALBRIER COLLECTIONTo improve the workers’ lot, Webster and a handful of other porters enlisted the help of Black labor organizer A. Philip Randolph and established the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters & Maids in 1925. (This was not the company’s first taste of collective organizing: In 1894, employees backed by the all-white American Railway Union initiated a strike that crippled the country’s railroads, prompting the federal government to wade in.) The Brotherhood sought, chiefly, reduced hours — commensurate with those of the company’s white conductors — and a living wage independent of tips. Despite the group’s initially inclusive choice of name, the maids did not prepare a separate list of grievances. This oversight could be because porters wildly outnumbered maids. Or perhaps, as historian Theodore Kornweibel Jr. contends, the omission stems from the fact that the Brotherhood “did not see women as a fundamental and permanent part of the labor force.”

Nevertheless, maids, such as Frances Albrier, joined the union and encouraged their coworkers to do the same. Female union membership continued in the face of Pullman retaliation, such as outright sacking or the loss of one’s pension, and well after “& Maids” was dropped from the Brotherhood’s name in 1929. Balancing their organizing with societal expectations proved difficult, however, as the maids operated under what Kelly called a “double bind of racism and sexism.” Chateauvert, in her book “Marching Together: Women of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters,” wrote that most maids, in a choice between being viewed as a “man” for working or as a “lady” dependent on a man, “compromised by paying their union dues and remaining silent.”

The porters’ female relatives, unburdened by such constraints, stepped into the void. Because they didn’t spend weeks at a time on the rails, they offered stability and permanence to the movement and were able to counter the rampant Pullman-as-blameless-benefactor narrative disseminated by both workers and executives of the South Chicago company. Perhaps most critically, these women didn’t report to Pullman. “Any overt involvement by anyone employed by the Pullman Company was suicide,” wrote Corrothers-Tucker. “So, it devolved upon the wives of the porters to do most of the organizational work.” She estimated that she visited 300-some porters’ homes in the D.C. area to answer questions, disseminate materials and drum up support. The local chapter convened at her house, with the blinds drawn and her husband, Berthea, none the wiser. (He may not have been the only porter in the dark. Corrothers-Tucker wrote about wives who signed their husbands up for the union and paid the dues themselves.)

Why We Celebrate Labor Day: Two of the Little-Known Heroes of Pullman

Chicago’s first National Park System unit showcases the rich history of a model town that shaped the nation.

See more ›Often, the women’s efforts were funneled through economic councils and, later, dozens of local ladies’ auxiliaries, groups designed to simultaneously bolster the Brotherhood and conform to socially accepted gender roles. While the women were not always united in their vision — some hewed to the laser-focused aim of achieving a contract with Pullman, while others lobbied to expand the groups’ scope, tackling issues from food insecurity to education — they remained devoted to Brotherhood success and proved to be fierce fundraisers. When the Brotherhood’s New York City chapter was yet again evicted for failure to pay rent, one wife circled the neighborhood, returning with $75 so the men could find a new place. Salon owner Lucille Randolph, a well-known Harlem socialite, introduced her husband, the Brotherhood’s president, to a bourgeois world of affluence and political connections. She also bankrolled his labor organizing efforts for nearly a decade, even doling out for his radical newspaper, “Messenger,” which extolled the importance of Brotherhood membership.

The road to recognition by the American Federation of Labor was decidedly uphill. The Brotherhood had to elude company spies, rebuild after an aborted strike, defeat a Pullman-backed union, overcome pushback from within the Black community and survive Depression-era furloughs. It took the intercession of a federal mediator in 1937 for Pullman to finally sign a negotiated contract. The document retained porters’ seniority rights, ensured a pay raise for both porters and maids, stipulated a 240-hour work month (the industry standard), and ensured the right to due process with respect to passenger-reported grievances. The union victory came at the expense of maids’ seniority rights, however. Essentially, “they sold out the maids,” Chateauvert said.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Chateauvert befriended Corrothers-Tucker in 1984, when the activist was over 100 years old and still navigating the stairs in the house she’d lived in since before the the days of the Brotherhood. After inheriting decades’ worth of union papers when Corrothers-Tucker died, Chateauvert scoured the files at the New York Public Library, Illinois Labor History Society and elsewhere to piece together an image of the women of the movement. Still, she found mere “breadcrumbs,” she said. “I searched high and low, and every place I could find. … I think there’s all sorts of stuff that was never actually recorded or is unknown. And I think that’s the sad part.”

Chateauvert would love to fill in those missing pieces, to flesh out the unsung lives of Pullman maids and porter wives. “Sometimes you wish, as a historian, you could be a fiction writer,” she said.

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.