Chicago's first National Park System unit showcases the rich history of a model town that shaped the nation.

The Pullman neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side is a small community that changed the country. This Labor Day, the doors of the factory at the heart of this beautiful model town will reopen to the public as a new visitor center, the cornerstone of Pullman National Monument.

Pullman National Historical Park

Few sites preserve the history of American industry, labor and urban planning as well as Pullman, America’s first model industrial town.

See more ›Pullman is central to understanding industry, labor and civil rights in America and the tense conflicts that led to the creation of Labor Day and the first African American union. As part of this grand opening, visitors can learn about some of the everyday workers whose names are largely unknown and who organized alongside famous national figures to have a significant impact on our country’s history.

Jennie Curtis and E.D. Nixon are two of these lesser-known heroes who were part of the struggle for human rights — and the reason we still celebrate Labor Day.

In 1894, Jennie Curtis was a 23-year-old seamstress in debt to industrial titan George Pullman. Pullman had created an empire building and servicing train cars that felt like hotels on wheels. Curtis sewed the luxurious drapes, pillows, tablecloths and other refinements that filled these cars. She worked in the Pullman Car Company’s sprawling factory and lived in the beautifully designed but tightly controlled model town of Pullman. Curtis and Pullman were both gifted and willful, but on opposite ends of a powerhouse company that had changed the way Americans moved around the country.

Curtis had been earning $2.25 a day, but after the economic panic of 1893, her wages were cut to 80 cents a day. Her father, also a Pullman employee, had died and left her with a $60 debt to the company. Her already tight wages were garnished, and she had to navigate verbal abuse from her supervisor and the bank.

Despite being an impoverished young adult, Curtis was not without influence. She was a gifted speaker and the president of the Girls Local Union 269, which had 125 members. Her struggles were also not unique. In response to the economic downturn, Pullman had prioritized his shareholders over his workers, cut wages without dropping rent, and dug in his heels as his workers’ frustrations grew. When Pullman dismissed requests for arbitration, the exasperated workers decided to walk off the job. Their strike was relatively small, but it came shortly before a national American Railway Union (ARU) convention hosted in Chicago. At the ARU convention, members considered whether to throw their national weight behind the Pullman workers.

Curtis was one of the most electrifying speakers at the convention. She connected the struggles of her fellow Pullman workers with the injustices faced by so many in the room and argued that “it will go on, brothers, forever unless you, the American Railway Union, stop it; end it; crush it out. And so I say, come along with us, for decent conditions everywhere!” That afternoon, she was one of 12 union leaders who entered the Pullman administration offices and asked bluntly, “Will you arbitrate?” Again, management refused to even acknowledge their grievances.

The ARU did come along, though. Eight days later, with Pullman’s heels still firmly planted, 125,000 workers on 29 railways refused to move trains that included Pullman cars. Train travel throughout much of the country ground to a halt.

“Pullman by Train,” a 2019 NPCA video about Pullman National Monument.

The strike came at a heavy price. Despite the best efforts of ARU President Eugene Debs to maintain calm, workers, law enforcement and rail management went toe-to-toe over who controlled the railways around the country, leading to significant violence. When angry strike supporters set fire to a railcar full of U.S. mail, President Grover Cleveland and his attorney general, who had previously worked for railway owners, used the incident to criminalize efforts by the union leaders and sent federal troops to Chicago to crush the strike. In the end, Curtis and the other Pullman workers were allowed to return to work only if they signed documents refusing future union membership.

Crushing the strike deeply undercut Pullman’s reputation as a visionary and threatened political support for Cleveland. The president was the leader of the Democratic party, which had strong labor support. Just as Cleveland was coming down hard on the side of management, he signed legislation that would make Labor Day a national holiday. It was a symbolic victory that attempted to smooth over the heavy blow to unions and temper the backlash from voters who were sympathetic to the Pullman strikers.

Curtis later gave testimony about the conditions that caused the strike and is still remembered for her key role with the union.

Long after the Pullman strike and first official Labor Day in 1894, Pullman porters, African American workers excluded from the early unions, continued to influence the national fight for civil rights.

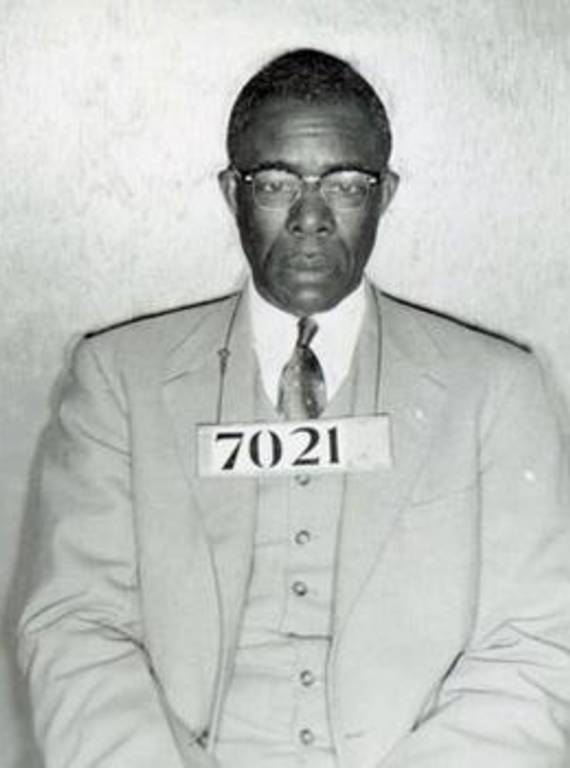

A 1955 arrest photo of Edward D. Nixon from his participation in the Montgomery bus boycotts. Though he lacked formal schooling, Nixon worked for decades as a Pullman porter and became an influential civil rights leader.

WikimediaWhen Rosa Parks was arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a Montgomery Bus on December 1, 1955, the man who bailed her out of jail was E.D. Nixon. The next morning, it was Nixon who called a young pastor named Martin Luther King Jr. and asked him to lead a boycott of the city bus system. Nixon had little to no formal education but had served as a Pullman porter and union member for three decades.

Pullman porters such as Nixon were the do-everything staff who serviced the Pullman train cars. His career gave him a path to the middle class and broad exposure to America as the trains crisscrossed the country. As Nixon later told author and historian Studs Terkel, when a Porter “walked into a barber shop … everybody listened because they knowed the porter had been everywhere and they never been anywhere themselves.”

But porters also endured brutal 100-hour workweeks and carried bags, served drinks, shined shoes, dealt with unruly children, prepared beds, diplomatically dealt with hangovers and indiscretions, and everything in between. Without tips, the porters’ pay would not have been enough to survive on, and racism was ever-present — in interactions with passengers, threats from Jim Crow America, and the basic caste system that divided passengers and servers.

Jennie Curtis had been able to join the railway union in part because Eugene Debs had made a strong pitch for women to have a role. Debs had made a similar pitch for African American involvement, but members voted 112-110 against the measure — part of a long track record of white unions excluding Black workers.

The porters galvanized and formed their own union in 1925. The union was led by A. Philip Randolph who would go on to lead the March on Washington in 1963 and introduce King before his famous “I Have a Dream” speech. The early years of organizing were rough as they faced very real threats and had few allies — but they endured and won. Twelve years to the day after the porters formed their union, they signed their first contract with the Pullman Car Company.

This organizing experience, and the expectation that victory was possible, empowered porters such as Nixon to play influential roles the early years of the civil rights movement. Porters donated their union halls for meetings, carried Black newspapers to the South, promoted anti-lynching campaigns, helped plot the Freedom Rides of 1961 and more.

Nixon was also a force in his community. He had been president of the Montgomery and Alabama branches of the NAACP and the first African American in the 20th century to run for office in Montgomery. His prominence and courage made him both a hero and a target — his home in Montgomery the first to be bombed during the civil rights protests of the 1960s. Ironically, if it were not for the long hours away from home that his job required, Nixon would have likely led the Montgomery bus boycott himself.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

Like so many labor and civil rights advocates who put themselves at risk in the pursuit of equity, Curtis and Nixon’s names were not included in school history books. But at Pullman, the National Park Service and partners such as the A. Philip Randolph Pullman Porter Museum and Historic Pullman Foundation capture stories like theirs and illustrate how those threads remain as relevant as ever.

This Labor Day, the grand opening of Pullman’s new visitor center will celebrate these people, both well known and little known, who shaped American history. The event will include city, state and national leaders who backed this national park site as well as the Pullman residents who organized to preserve the community and its unique history over the decades. NPCA was proud to collaborate with these partners to create this neighborhood national park and to connect people to the town and its dedicated people, past and present.

About the author

-

Mark Mesle Former Midwest Field Representative

Mark Mesle Former Midwest Field RepresentativeMark Mesle is the Midwest Field Representative in NPCA’s Chicago office. Mark works with community groups and local officials to build support for parks throughout the region.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Midwest

-

Issues