Winter 2023

Case Reopened

A major school desegregation victory in Colorado was all but forgotten. A century later, it’s getting its due.

Gonzalo Guzmán was conducting research on the experience of Latino students in Wyoming when he came across a mention in a 1914 newspaper of “Mexican” parents protesting discrimination in Alamosa, Colorado. “It wasn’t even a full sentence,” Guzmán said. A historian and assistant professor of education at Macalester College in Saint Paul, Minnesota, Guzmán was curious, so he searched Colorado newspaper archives and found that the protest eventually led to a legal victory by Francisco Maestas and other parents in a desegregation case. He also contacted Rubén Donato, an educational historian at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Surely, Donato, a pioneer in the field of Latino education history, would have heard of the Maestas case. It turned out he hadn’t.

“As an academic I was shocked that nobody had done a study on it,” Donato said.

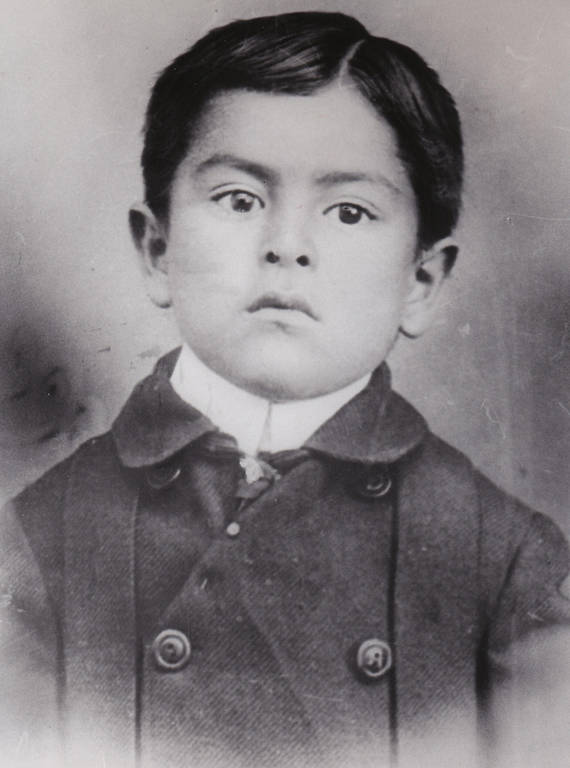

A portrait of Miguel Maestas, the 11-year-old at the center of a 1914 school segregation court case in Alamosa, Colorado.

COURTESY OF DR. RON W. MAESTAS AND TONY SANDOVAL, MEMBERS OF THE MAESTAS FAMILYGuzmán, Donato and Jarrod Hanson, an education professor at the University of Colorado in Denver, teamed up to uncover the full story. They reached out to Judge Martín Gonzales in Alamosa to ask for the case file. Gonzales, despite generations-deep roots in the area and a judgeship in the very district where the case was argued, had never heard of it either. He found the file and sent it to the academics, who quickly assessed the importance of the long-buried Maestas case.

“We, as educational historians, can pretty confidently say that this is the first Mexican American-led school desegregation challenge in the United States,” said Donato, whose paper, co-authored with Guzmán and Hanson, was published in 2017. “That’s huge!”

Still, Gonzales, descendants of the Maestas family and other locals felt a case of this significance deserved to be recognized beyond the confines of academia. Together with the three professors, they formed the Maestas Case Commemoration Committee. The school at the center of the case and the old courthouse were gone, but committee members thought a commemorative marker was needed, so they commissioned a bronze relief by New Mexico-based sculptor Reynaldo “Sonny” Rivera. In October, the bronze was installed in the new courthouse, which was completed four years ago.

“It made some sense to give this courthouse a proper christening to tie it back to where it came from,” said Gonzales, who retired recently.

Stewards & Storytellers

Essex National Heritage Area in Massachusetts is one of dozens of heritage areas making America’s best idea even better.

See more ›Alamosa is the commercial hub of the San Luis Valley, a 120-mile-long basin in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico that includes Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve. The small city also sits inside the Sangre de Cristo National Heritage Area, a nationally significant landscape managed by local entities in collaboration with the National Park Service, which administers some funds and offers technical assistance. NPCA has supported efforts to increase awareness of the Maestas case and is working with the Alliance of National Heritage Areas and other allies to renew funding for Sangre de Cristo and the 54 other national heritage areas, whose federal money is at risk, said Tracy Coppola, NPCA’s senior program manager for Colorado.

Native American presence in the region dates back at least 10,000 years, and the valley was later populated by people of Spanish and early Mexican descent. It became part of the United States in 1848 after the Mexican-American War. Katie Dokson, a member of the Maestas committee whose family has lived in the valley for eight generations, said the term she uses for people like her is “Hispano.” “We all come from this mixed lineage that has become Spanish-speaking, so it’s a hard category to explain.”

The Maestas family had long been established in the area by the time the Alamosa school board directed all Hispano children to the “Mexican School” located in the southern part of town in 1912. A group of parents complained to local and state authorities, arguing that the move was tantamount to racial discrimination, which ran counter to the Colorado Constitution. Francisco Maestas thought attending the Mexican School was not only inconvenient but dangerous for his 11-year-old son Miguel, as it involved crossing several railroad tracks.

So this community here, when they saw that their children were being segregated in an inferior school, they did something about it.

In the fall of 1913, after their complaints had gone unheeded, the parents decided to pull their children from the school and file a lawsuit in the district court. They raised money for legal fees and received support from a local civil rights organization and E.J. Montell, a Catholic priest, who found a young lawyer in Denver named Raymond Sullivan to represent them. The school board denied discrimination accusations because Hispano children were officially considered “white,” but testimony contradicted that assertion, according to a newspaper account.

“We had some board members that said, ‘I don’t want my kid to go to school with Mexicans,’” said Ronald Maestas, a relative of Francisco and Miguel who has researched the family’s history. “That was the attitude at that time.”

Unburying the Past

The Blackwell School, a rare remnant of segregation in West Texas, is poised to become the next national park site.

See more ›The board also argued that Hispano children were directed to the Mexican School because of their inability to speak English, but that rationale was debunked in court when Miguel and other children responded to questions in English. In March 1914, Judge Charles Holbrook rejected the board’s arguments and ruled that all children competent in English should be able to join the school of their choice.

No one knows how many children switched schools, as records were lost. What happened to Miguel later in life has also largely been lost to history, but Ronald Maestas learned from Miguel’s daughter Eva that he eventually moved to New York where he tried to become a professional boxer.

Two years after the ruling, Maestas’ lawyer came back to Alamosa to fight — and win — another discrimination case against the owners of a bowling alley. The ongoing fight for equal rights explains in part why the Maestas case was largely forgotten, Gonzales said. “This was just one struggle of many,” he said, “and as time would have it, things disappeared from the memory.” Gonzales also said the fact that the case was apparently never appealed meant it was not widely disseminated.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›The members of the Maestas committee have worked hard to make sure the case is not forgotten once more. They installed an exhibit in Colorado’s Capitol, where the legislature passed a resolution honoring the struggle to integrate the state’s schools, and the committee plans to take a replica of the bronze relief to locations around the state. And they hope that the case will become part of Colorado schools’ curriculum so that students can be inspired by the story of a group of determined Hispano parents.

“What I get out of it is that Mexican Americans have always cared about the schooling of their children,” Donato said. “So this community here, when they saw that their children were being segregated in an inferior school, they did something about it.”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.