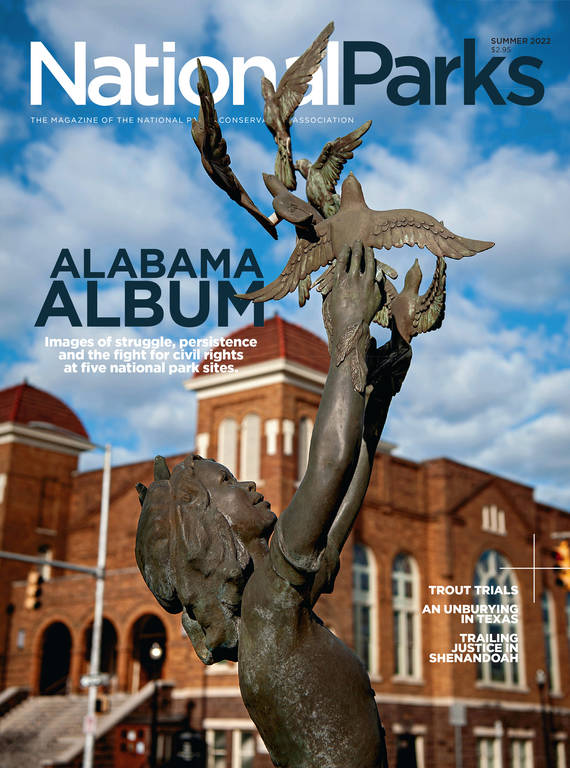

Summer 2022

Unburying the Past

The Blackwell School, a rare remnant of segregation in West Texas, is poised to become the next national park site.

Mario Rivera remembers his first day at the Blackwell School vividly. Rivera, who was 7 years old at the time, had grown up in Marfa, Texas, speaking Spanish with his friends and family. But that fall day in 1950 when he sat down in the white adobe building with the creaky wooden floors, Rivera was confused to hear his first grade teacher address him and his classmates — all of them Hispanic, most of them native Spanish speakers — in English, a language he didn’t understand. “She didn’t speak Spanish — or if she did, she never admitted it,” he recalled.

During the Jim Crow era, laws mandated separate schools for African American and white children in many parts of the country. But throughout the Southwest, the story of racial discrimination in education followed a different path, one that’s much less well known. While the segregation of Black children was enshrined in the law, segregation in Marfa was maintained unofficially — the school district assigned Hispanic students to Blackwell, while white children were sent to a different elementary school. Segregated — and underfunded — schools for Hispanic students were scattered throughout Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado and California, though it’s unclear exactly how many.

One of the school’s principals and its namesake, Jesse Blackwell, believed that students who grew up speaking Spanish at home were at a disadvantage, and later administrators required that students speak only English while on school grounds. Rivera, whose parents had immigrated from Mexico, picked up English quickly, but while he has fond memories of his dedicated teachers at Blackwell, other alumni recall an educational atmosphere that demeaned their heritage. Most teachers were white, and some students were paddled for speaking Spanish. In 1954, a seventh grade teacher held a schoolwide funeral for “Mr. Spanish,” instructing students to symbolically bury the language in a miniature coffin.

The original Blackwell School building, shown here in 1909.

COURTESY OF THE BLACKWELL SCHOOL ALLIANCEThe 1959 class of Mildred Shannon.

COURTESY OF THE BLACKWELL SCHOOL ALLIANCEThe first grade class of Mary Louise Mitchell at the Blackwell School in Marfa, Texas, 1947.

Courtesy of The Blackwell School AllianceDecades later, the Blackwell School and this underexplored period of Texas and American history are being reexamined. The school is on track to be designated a national historic site, which would mean that the story of Rivera and others like him will be fully told at last. “The history of Texas, it’s not just the Alamo,” Rivera said. “There’s other people that should be mentioned.”

The Blackwell School operated from 1909 to 1965, when an integrated elementary school opened in Marfa. Within a decade, most of the buildings on the former campus were demolished. The main remaining structure — that white adobe building where Rivera had sat on his first, disorienting day of school — was eventually used for storage. There were periodic rumors that the school district might demolish the building, or that it would be sold and transformed into a gallery — a real risk in a town that was increasingly becoming an art-tourism hot spot.

In 2006, Blackwell alumnus Joe Cabezuela and other former students formed a nonprofit to preserve the school and stave off these threats. The Blackwell School Alliance was granted a 99-year lease from the school district and began transforming the building into a museum. They also started recording oral histories and collecting old photographs and other ephemera to commemorate the school’s history. The following year, the group held a reunion, where they staged a mock disinterment of Mr. Spanish.

Victory! Blackwell School Becomes America’s Newest National Park Site

With a stroke of his pen, President Biden directed the National Park Service to save history at this former segregated school for…

See more ›When Gretel Enck, a recent transplant to Marfa, took a tour of the Blackwell School in 2015, she was so moved by the story that she began volunteering to host weekly open houses at the school. The more time she spent in the building, the more she understood the importance — and the challenge — of preserving Blackwell’s history. Most similarly segregated schools across the Southwest had been demolished or repurposed. As far as anyone could tell, the Blackwell School was the only segregated school serving a Hispanic population that had been turned into a museum. But the building was more than a century old, and in rough shape, with plaster cracking off its facade in sizable chunks. Also, the alliance had collected hundreds of old photographs, but preserving and digitizing them was a daunting prospect. Meanwhile, the Blackwell alumni were aging. Up until then, the museum had relied on their testimony and their volunteer hours to preserve the history of the Blackwell School, but clearly, more support was necessary.

When Cabezuela moved to El Paso, he asked Enck to serve as the first president of the alliance who hadn’t attended the school. “The first time he asked, I said no,” Enck said, laughing. “But when he kept pressing, I agreed.” Although Enck was a relative newcomer, she had experience working in historical preservation throughout the National Park System, including a stint at Manzanar National Historic Site in California, which memorializes one of the sites where the U.S. government incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II. “I knew that the [National Park Service] is good at telling these challenging stories about our history,” Enck said.

After a chance coffee shop encounter with Will Hurd, then serving as a member of the U.S. House of Representatives’ Texas delegation, Enck began lobbying to get the Blackwell School listed as a national historic site. She and other members of the alliance put together a detailed budget and commissioned a report on the site’s historical structures, engaging many alumni in the process. When asked about their time at Blackwell, former students expressed everything from pride and anger to gratitude and sorrow. “It’s a mosaic of experiences,” Enck said.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›In 2021, Hurd’s successor in Congress, Rep. Tony Gonzales, together with Rep. Filemon Vela, introduced a bill seeking to establish the Blackwell School as a national historic site, an effort supported by NPCA. During a time of heightened political turmoil, the bill received overwhelming bipartisan support in the House of Representatives, where it passed 417-8. (The Senate passed a modified version of the bill, so the House will have to vote on it again; if it passes it will go to President Joe Biden to be signed into law.)

As the designation works its way through the halls of Congress, the heightened attention on Blackwell is already inspiring younger generations. Daniel O. Hernandez, a 30-year-old whose maternal grandmother attended the school, now sits on the board of the alliance. “Growing up in Marfa, I don’t recall understanding what Blackwell was,” he said. That lack of understanding was, he realized later, part of a broader neglect of Mexican American history in the story of the United States. “I think this could be an important site to teach kids like me, kids across the country, a more holistic story about what it’s meant to be an American in all these different eras,” he said. “It’s so important that we talk about this period of de facto segregation, because at the end of the day, it is a part of our story.”

About the author

-

Rachel Monroe Contributor

Rachel Monroe ContributorRachel Monroe is a contributing writer at The New Yorker and the author of “Savage Appetites: True Stories of Women, Crime, and Obsession.” She lives in Marfa.