Spring 2022

Obed Refuge

How a backyard national park helped heal a family in transition.

In 1998, I was a stressed-out Knoxville suburban dad confronting the end of an 18-year marriage and desperately hoping to find a refuge where I could build a simple cabin and create a nature-infused space for strengthening bonds with my daughters, Challen, then 9, and Logan, 7.

I knew I didn’t want to host my girls on their weekend visits in a nondescript apartment complex largely occupied by other downcast newly divorced fathers. Also, in my youth, I had spent nearly six months in the embrace of the Eastern wilderness along the Appalachian Trail, and I longed to regain that intimate connection with the natural world after having spent far too many years as a prisoner of tidy subdivisions with manicured lawns and cookie-cutter houses.

The view from Lilly Bluff Overlook at Obed Wild and Scenic River.

NPS/M. FOSTERMy search for land began with a stop at Obed Wild and Scenic River, which sits on the rugged, wind- and water-sculpted Cumberland Plateau of Tennessee. At the visitor center in Wartburg, I asked the ranger behind the counter if she knew of anyone with property for sale in the area. Her response suggested that my timing was not only perfect but perhaps even prescient. “Wow,” she said. “A guy stopped by here five minutes ago and left his business cards. He’s selling property on the boundary of the national park.”

Soon, I was walking down a recently cleared dirt road with the landowner, who was selling parcels of his 68-acre holding for $1,800 per acre. As his first customer, I had dibs and chose 10 acres at the very end of the road and bordering on Clear Creek, one of the park site’s two main waterways.

Within a few days, my dad and I visited the property and staked out the cabin site, imposing the rigid lines of a 20-by-30-foot rectangle on an otherwise wild patch of forest. With the imbedded stakes in place and connected by pink surveyor’s tape, I could begin to visualize my new home rising from the earth.

Six months later, in January, a local builder handed the girls and me the keys to our snug dwelling set beneath a dense canopy of interlacing hemlocks, pines and hardwoods. An 18-foot cathedral ceiling made the relatively small main room seem more ample, a loft accessed by a 10-foot ladder would serve as my writing space, and a woodstove was our sole source of heat.

Obed, just 5,000 acres, is tiny by Park Service standards, but in the end, it seems, a national park’s size or renown has little to do with its powers to recompense earnest seekers intent on finding healing space and reorienting lives temporarily tipped out of balance. Ultimately, the park — and our backyard proximity to it — would help shepherd my daughters and me through a difficult transition and deliver us to a place of wholeness and peace.

At Home in the Woods

The cabin may have been new to Challen and Logan, but the outdoors decidedly was not. Starting when they were old enough to grip my hand and toddle down a trail, the girls had been immersed in the wilds. Predictably, within a few hours of crossing the threshold of our new cabin, they were outside exploring the surrounding forest with the zeal of travelers newly arrived in a land of wonders, identifying familiar plants, overturning decaying logs to find blue-tailed skinks and spotted, crimson salamanders, pointing out hawks circling overheard and engineering the structures of a fanciful village — dubbed “Land of the Toads” by Logan — from sticks, leaves and stones.

I soon joined them, and together we walked a short distance to where a line of trees girded with surveyor’s tape defined the park’s boundary. Beyond, we reached a rocky crag on the rim of the Clear Creek gorge. The sheer sandstone walls on the far side reflected the erosion that had shaped them over eons. We could hear the roar of water as it thrashed against giant boulders on its downhill course, but the river, 60 feet below, remained obscured behind a dense screen of trees.

©KAREN MINOT

Our golden retriever, Benton, trailed us for a time before embarking on a more extensive reconnaissance and returned an hour later soaking wet. He clearly had found his way to a body of water — presumably Clear Creek — offering proof of a rare cleft in the otherwise continuous gorge rim and one that might afford us access to the river. Benton’s frequent excursions inspired the girls and me to christen the cabin and grounds Benton’s Run in his honor.

Within a few weeks, our forays led us farther afield and into Obed, often following Benton’s lead. Of particular interest, with summer yet several months away, was whether the river at the base of the bluff would offer an inviting pool or a forbidding jumble of boulders. On a cold afternoon, with snowflakes swirling around us, we departed the cabin and crossed into the park. A hundred yards beyond, Challen announced discovery of the fracture in the gorge rim. We slipped below the bluff line and descended past rock outcroppings as big as school buses, and soon Clear Creek came into view. In choosing our parcel of land, I had selected wisely.

Challen, at age 10, during one of many summer afternoons spent swimming in Clear Creek with her friends and their families.

COURTESY OF DAVID BRILLOur future swimming hole extended 100 yards from mouth to mouth, spanned 75 feet from side to side and, as we would later find out, was more than 20 feet deep. A gray mass of sandstone, the size and shape of a sperm whale, began near the shore and tapered to a ledge at the waterline. We would later name the ersatz whale the “Rock of Contemplation,” owing to the mood of reflection that, in future months, seemed to settle over anyone who sat on it, with knees gathered to chest, peering out at the steep walls of forest.

Solitude’s Downside

At first, the cabin’s isolated setting an hour from the girls’ home in West Knoxville served to sequester them from their friends at a time when they needed them most. But, by summer, we learned that the antidote to social isolation was as simple as extending invitations to the girls’ friends and families to come visit, and soon, dozens of moms, dads and kids were showing up on weekends and following Challen and Logan along our well-worn paths into Obed.

The swimming hole became a prime destination, and I recall long, sun-drenched Saturday afternoons with children — some buoyed by inflatable floats, others secured in life vests — bobbing in the water under the approving eyes of parents perched on the Rock of Contemplation. Benton, sleek as an otter in the deep blue-green water, made his rounds, visiting with each swimmer in turn and on occasion offering his tail as a tow rope. Over the years, our access to the swimming hole has remained sole and exclusive, except for the occasional kayakers who drift through and invariably ask, somewhat mystified, “Where did you all come from?”

As the months passed, I cherished my weekends with the girls, but the intervening periods found me largely alone in my little cabin. Beset by restlessness, I often sought solace in Obed and followed the trail down to the creek. Perched on the rock, I’d watch great blue herons glide the length of the gorge before skidding in for landings in shallow water where the scales of dozens of small darters glistened in the sun. Lush green ferns lined the shoreline and fringed the rocks that probed above the river’s surface.

SIDE TRIP: Slumbering in the 19th Century

The beauty of the setting often filled my heart to bursting, but the experience was diminished by the absence of someone to share it with. My hermitage — the embodiment of a fantasy I had first entertained along the Appalachian Trail’s final miles — had become a place of self-imposed exile.

A Little Help from My Friends

In a clear case of projection, I concluded that Benton was lonely and acquired a second golden retriever, a tiny fluff ball named Zealand, to keep him company. But ultimately, I realized that, much as the girls needed their companions, I also needed mine.

One Saturday evening, while I prepared dinner, Challen, sensing my frame of mind, approached and asked me if I was OK. Parents mistakenly assume that masking our occasional blue moods will somehow shield our children from them — a tactic that’s entirely dismissive of our kids’ ability to intuit the emotional spaces we occupy. In response to Challen’s question, I came clean.

“I really miss you guys,” I said. “And this place can get pretty quiet when you’re not here.” But in due time, the cabin began to exert its allure on friends who had never shed their childhood love of stomping around in the woods. J.J. Rochelle, an old friend from nearby Oak Ridge, visited us so frequently that the girls began to call him their “second-place Dad.”

On a cold, rainy New Year’s Eve, J.J., the girls and I followed the beams of our headlamps downriver along the bluff line to where a faint trail cut below the gorge rim. After skirting along the base of a sandstone wall adorned with dripping icicles, we arrived at a gaping recess in the rock — a giant natural cathedral that had first been occupied by humans 12,500 years ago. I had previously explored the feature during daylight but never in darkness. A 30-foot ceiling capped the shelf cave and sheltered us from the elements. We had brought a dozen votive candles, which we carefully placed on tiny ledges in the wall. With the approach of midnight, while our friends back in civilization noshed on canapés, the four of us rang in the new year sipping hot cocoa in the flickering light.

Kent Ernsting, a Cincinnatian I had known since grade school, and Russ Hirst, an English professor and purveyor of groan-worthy puns, also became regular fixtures at the cabin, often arriving with their families. Kent would eventually buy nearby property on Clear Creek and become a part-time neighbor. And Russ, who was never without his mask and snorkel, routinely entered Clear Creek regardless of the season or ambient air temperature, and he often emerged from the river enveloped in a cloud of steam. Dan Howe, my old AT hiking buddy, made the trip over from Raleigh once or twice a year, typically proffering a pot of chili and a bottle of fine bourbon. The latter, combined with a campfire, never failed to prompt a spate of old trail tales — most of them true.

While my friends’ visits were occasional and of short duration, I was about to welcome a companion who would arrive intent on staying.

The Wicked Stepmother

I had met Belinda Woodiel in 1992, while both of us worked for the University of Tennessee. Though I was married at the time, I’ll admit to being captivated by Belinda’s smarts, calm demeanor, bright brown eyes and curly chestnut hair.

After a couple of years, Belinda left the university for a new job, and we rarely saw each other, though she remained on my mind. Then, one day, a mutual friend mentioned that he had run into her and suggested that I give her a call. Notably, he referenced her by her maiden name.

By 2003, both of us had emerged from our first marriages, and we agreed to meet for a beer in a downtown Knoxville pub. After my first pint, I mustered the nerve to ask Belinda if she would consider dating me. She paused; I braced. “I’ve had a crush on you for 10 years,” she answered, which I took to mean yes. Three years later, almost to the day, we were married. Our choice of venue, Obed, required little deliberation.

Exchanging wedding vows on Lilly Bluff Overlook, March 4, 2006.

COURTESY OF DAVID BRILLThrough the years of our courtship, Belinda had come to love the park as much as I did. And while I, as tour guide, led her to some of my favorite destinations — the swimming hole, the shelf cave, hiking trails winding through dense forests or along open ridges — she, a self-professed nature nerd, schooled me in the names, both common and Latin, of Obed’s profusion of botanical specimens and taught me to identify bird species by their distinctive calls.

Our first weddings had been large, traditional ceremonies marked more by pomp and formality than intimacy, and we wanted this occasion to be largely unadorned and ornamented by nature. On a crisp, clear March Saturday, surrounded by immediate family and one wedding crasher — my ever-supportive friend Kent, who insisted on being there for me, invited or not — Belinda and I exchanged our vows on Lilly Bluff Overlook, a large observation deck positioned on the rim of the Clear Creek gorge. The minister of Belinda’s Methodist church officiated; Logan played “Simple Gifts” on her fiddle. And with that, our blended family — including Benton, Zealand and a cat named Elle — was complete.

From the beginning, Belinda served as ally, friend and confidant to Challen and Logan, and her attention to the physical and emotional needs of young girls transitioning into adolescence supplanted my own well-intentioned but sometimes awkward efforts to lend support. Out of love, deference and a surfeit of irony, the girls soon began calling her their “wicked stepmother,” as in wicked awesome.

After eight years in the cabin, the girls and I assumed we had discovered all — or at least most — of Obed’s nearby hidden gems, but Belinda, acutely attuned to nature’s varied sights and sounds, soon proved us wrong. After a heavy winter rain, Belinda, standing on the deck, heard Clear Creek’s dominant roar rising from the gorge, but she also discerned a more subtle sound of rushing water to the cabin’s south, an area the girls and I had yet to explore fully.

Equipped with my chainsaw, I cut a path through a tangle of trees brought down by a recent ice storm. We soon crossed the park boundary and arrived at a sloping 50-foot whitewater cascade beneath towering hemlocks and edged by a lush rhododendron thicket. Afterward, it would become a favorite spot for lolling in hammocks and a new natural wonder to share with visiting friends, who often seemed reluctant to leave the cataract’s soothing presence.

Exploring Obed’s Epicenter

The area surrounding Lilly Bridge, a 10-minute drive from the cabin, serves as Obed’s epicenter, where numerous notable features converge. The overlook where Belinda and I were married is situated at the upper reaches of more than a dozen bolted rock-climbing routes. Lilly Bridge itself provides the perfect vantage point for watching kayakers navigate Clear Creek’s rapids. And the Point Trail, a 3.8-mile out-and-back route, culminates on a narrow rocky ridge that affords views of Clear Creek on one side and Obed River, the park’s namesake and other main waterway, on the other. The trail’s terminus is poised 100 feet above where the two rivers merge.

As the girls grew and developed sturdy hiking legs, the Point Trail became a frequent weekend destination, and though we’ve hiked it dozens of times over the years, the expression that one never steps into the same stream twice likewise applies to mountain pathways. In spring, ephemeral wildflowers — dwarf crested irises, spring beauties, foamflowers, bird’s foot violets, lady’s slippers — blanketed entire hillsides and were soon succeeded by the pink, softball-sized blossoms of rhododendron and the cream-white florets of mountain laurel. After rains, scores of mushrooms sprouted trailside, and the gnarled ledges of bright orange shelf fungi emerged on downed trees. Fall foliage burnished the mountainsides in reds and golds, and in winter, when snow blanketed the trail, tiny footprints betrayed the movement of foxes, raccoons, rabbits and field mice. At trail’s end, hot cocoa from a thermos warmed us as we watched snowflakes waft down into the river gorge and gather on hemlocks’ outstretched branches.

The blended Brill family, including dogs Zealand and Benton and Elle the cat.

©RON BRILLThe author and his longtime friend, Kent Ernsting, with their children on the “Rock of Contemplation” in Clear Creek. Benton, post-swim, shakes the water from his fur.

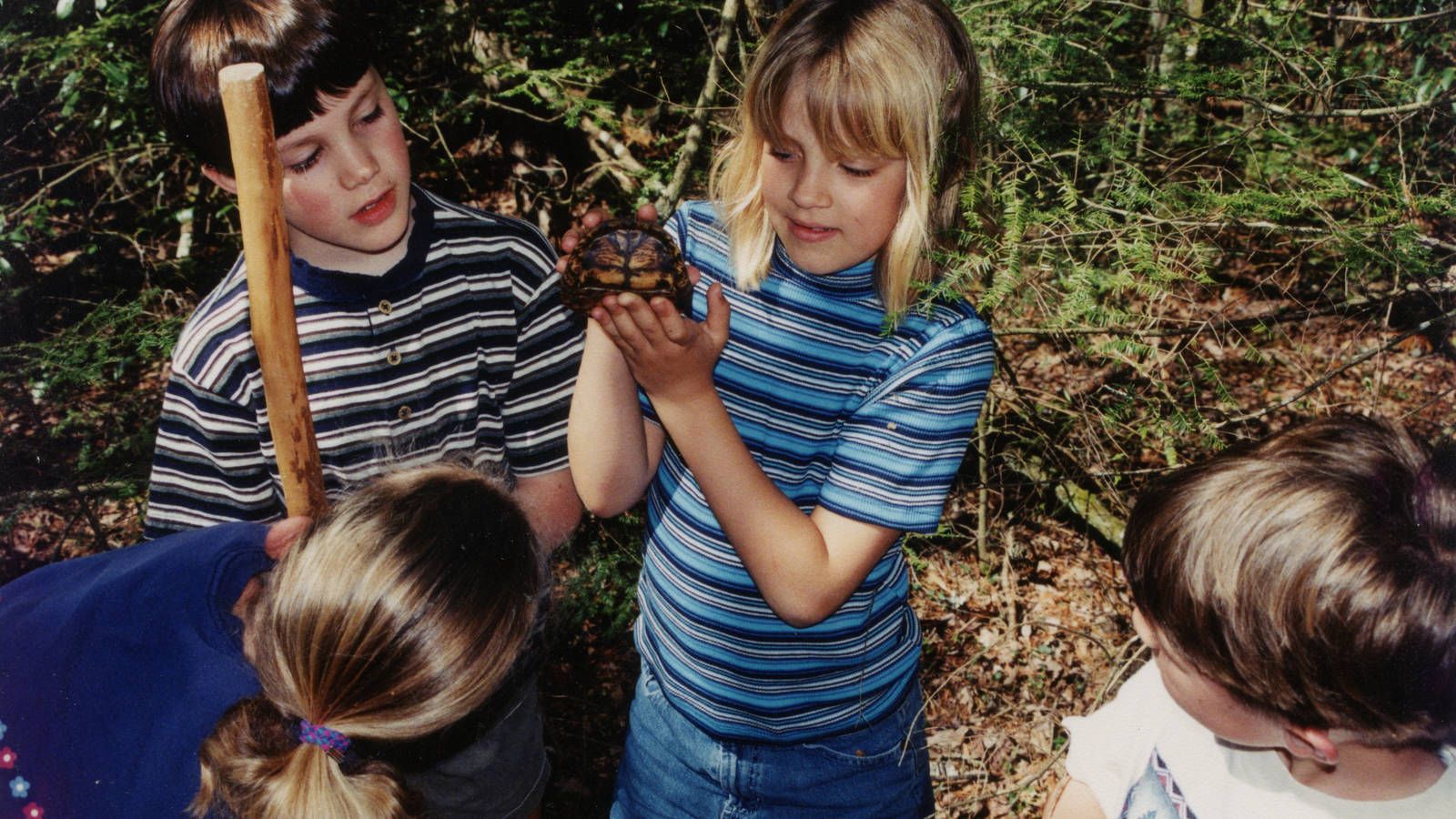

COURTESY OF DAVID BRILLLogan shows a box turtle to her sister and friends.

COURTESY OF DAVID BRILLThe author and some friends stage a winter songfest in front of a fireplace on the cabin’s deck.

COURTESY OF DAVID BRILLThree generations of Brills at Obed Wild and Scenic River. From left: David, Ron, Nancy, Challen, Logan and Belinda.

COURTESY OF DAVID BRILLA Starry Night Affirmation

The Cumberland Plateau’s ancient landscape imparts a useful lesson on the impermanence of things, whether they be geologic formations under relentless erosive assault or transient human-scale problems that amount to mere blips in the context of the long-elapsed eons.

When I reflect on my family’s early years along Obed’s margins — years tinged by worry and doubt — they seem distant and remote, as if elements of someone else’s life. The two young girls who first crossed the cabin’s threshold 24 years ago are now adults and live two hours away in Nashville. Logan and her partner, Grant, have been an item since high school, and Challen and her husband, Adler, who married in 2019, now are parents to an 18-month-old son, Norris, Belinda’s and my first grandchild.

In a perfect world, pets would enjoy the same lifespan as their human companions, but Benton, Zealand and Elle are now gone, interred in a special plot not far off the back deck. Zebulon, a lovable but frenetic Labrador and Tater Tot, a tiny kitten who wandered out of the forest one night, have assumed their predecessors’ nurturing roles, though they will never take their places.

When the four generations of my family gather at the cabin these days, we nearly always venture into the park, lured by the promise of thundering waterfalls, mountain trails hemmed by wildflowers, open ledges affording views of wild rivers. And then there are the star-flecked night skies. When darkness descends over the plateau and the nocturnal denizens of the forest begin to stir, a primordial urge overtakes us humans and unfailingly compels our attention toward the spectacle that sprawls above us.

Over the years, I have become accustomed to hearing city folk audibly gasp when they first behold the cabin’s night sky, absent the intrusion of artificial light. Stargazing in designated International Dark Sky Parks like Obed — one of only around 80 in the United States — provides a portal into the infinite reaches of space and reminds us that our tiny blue marble is in good cosmic company. Our visitors frequently have lain swaddled in sleeping bags, staring reverently upward, as meteors streaked across the heavens, trailing golden glitter in their wakes.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

That same night sky is what finally persuaded my mother that building a cabin in the middle of nowhere wasn’t the imprudent folly she had once believed it to be. Initially, she had been concerned that my choosing to live more than an hour away from my daughters would somehow erode our closeness rather than strengthen it.

But on a clear, moonless fall night, she began to fathom fully my unwavering affection for our wooded refuge. Following an evening meal, the family had walked to an open meadow a few hundred yards down the gravel drive and gazed upward at a sky dense with stars and planets.

Frost had stiffened the blades of grass, and the broad, phosphorescent sash of the Milky Way, clearly visible, bestowed sufficient light to cast us in silhouette. Mom gripped my hand.

“I’ve never seen stars like this,” she said. “I finally understand why you love this place so much.”

In January 2019, near midnight, an overcast sky cleared just in time to reveal a moon transitioning to blood red as it passed into Earth’s shadow. And two years prior, daylight slowly descended into darkness during a total solar eclipse, with Obed on the prime viewing pathway. As Belinda and I watched the moon blot out the sun, darkening all but the thin shimmering ring of the corona, we heard the call of a bewildered barred owl issue from the forest.

The solar and lunar eclipses were singular and marvelous events that Belinda and I will never forget. But in the course of our lives here, it’s the more commonplace observations and experiences — turkeys scattering through the forest, deer bending to graze in open meadows, wisps of morning fog wafting through stands of hemlock and pine, dogwood blossoms unfurling in the warmth of spring sunshine — that impart an abiding sense of belonging, of being more residents of, than visitors to, a wild, untamed world of beauty and wonder.

About the author

-

David Brill Contributor

David Brill ContributorDavid Brill’s writing has appeared in dozens of publications, and he is the author of five nonfiction books including “Into the Mist: Tales of Death and Disaster, Mishaps and Misdeeds, Misfortune and Mayhem in Great Smoky Mountains National Park” and “As Far as the Eye Can See: Reflections of an Appalachian Trail Hiker,” now in its eighth (30th anniversary) printing.