Spring 2021

Like Clockwork

Ready or not, the Brood X cicadas are coming — maybe to a park near you.

When Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts in Virginia staged a live performance of “A Prairie Home Companion” on May 29, 2004, there were some uninvited — but not unexpected — guests in attendance. Lots of them, in fact.

“The 17-year cicada — Brood X cicadas — have hatched. And they are flying among us,” said Garrison Keillor, host of the longtime public radio program. “There’s one on you right now. Don’t panic. It’s OK,” he quipped, before launching into a folksy, old-timey tune called “Cicada Song” that distilled the epic lives of the curious insects into eight bouncy rhyming couplets.

Now, the offspring of those 2004 periodical cicadas — trillions of them — are poised to make their dramatic, noisy return this spring, as Americans across 15 states, from North Carolina to Indiana to New Jersey, will soon discover. And many parks in the mid-Atlantic region, including Gettysburg National Military Park, Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park and sections of the Appalachian National Scenic Trail, will be right in the thick of it all.

If the spectacle isn’t coming to your own backyard, you can always experience it on America’s Front Yard. “We’re fortunate to be a part of the area where Brood X emerges,” said Leslie Frattaroli, natural resources program manager for the National Mall and Memorial Parks. “Natural events like this are a perfect showcase for the importance of natural resources in urban areas.”

A Man Beyond Measure

While harmless to humans, Brood X cicadas will definitely leave a mark on the landscapes where they appear. The dime-sized holes caused by emerging nymphs allow air and water into the ground, and the carcasses of dead adults return nutrients to the soil. But there will be damage, too. Female cicadas lay their eggs in the slender branches of deciduous trees by first sawing a slit with their ovipositors, a behavior that has no long-lasting effect on mature trees but will cause the tips of their branches to wither, droop and drop. Saplings and recently transplanted trees are at greater risk and can best be protected by covering them in netting, as chemical insecticides cause significant harm to the ecosystem. The cicadas themselves can be forgiven for all this commotion — after all, they’ve got only one thing on their insect minds.

“Those teenagers have been underground for 17 years and, hey, in May, they’re coming up,” said Michael Raupp, professor of entomology at the University of Maryland. “It’s going to be a big boy band up in the treetops as the males try to attract their mates.”

Unlike the annual cicadas that appear in much of the country during the dog days each summer, periodical cicadas (Brood X actually includes three species that all belong to the genus Magicicada) have a life cycle that beggars belief. After spending 17 years underground (or 13 years for some broods) sucking sap from tree roots, they emerge as one in staggering numbers — more than their many predators can eat. The survivors take to the treetops, and the cacophonous sound of male cicadas seeking willing female partners soon fills the air. After weeks of what may well be the world’s biggest and noisiest public display of affection, the last of the cicadas dies away. Once the eggs hatch, nymphs no larger than grains of rice rain down from the treetops and burrow into the ground, where they will wait to repeat the cycle many years later.

“This has been going on for eons. This happens nowhere else on the planet except right here in eastern North America,” said Raupp, who likens the phenomenon to a National Geographic special one can view firsthand. “You can observe every interesting element of biology: birth, death, predation, courtship — it’s just going to be a fascinating opportunity to learn about nature.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

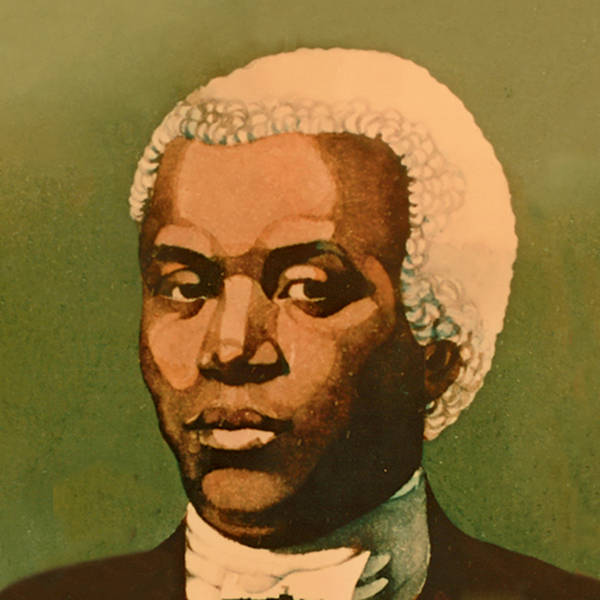

See more ›Some of our predecessors may have been a bit more practical. Native Americans feasted on cicadas — the emerging nymphs are soft and shrimplike and, by some accounts, taste a bit like asparagus. (Raupp, who once shared a skewer of cooked cicadas with host Jay Leno on “The Tonight Show,” described their flavor as delicate and nutty. Leno remarked that they tasted better than Cheetos.) But the periodical cicadas also fed suspicion. Some tribes believed they were harbingers of war and famine, and early European settlers equated them with biblical plagues of locusts. A report on the coming emergence in the April 3, 1751, edition of the Maryland Gazette ended with this plea: “May God avert our impending Calamities.” Eventually, apprehension gave way to fascination. Scientist Benjamin Banneker kept a detailed personal journal that revealed his preoccupation with and careful study of the insects that, as he wrote in a June 1800 entry, “like the Comets, make but a short stay with us.”

Whatever your take on the impending arrival of the Brood X periodical cicadas, one thing is for certain: After everything we’ve experienced lately, it will be reassuring to watch Mother Nature do her thing, on cue and as predicted, just like clockwork.

“You can count on it,” Raupp said. “It’s as reliable as the blooming of the cherry blossoms on the Mall every year. It is going to happen, absolutely.”

About the author

-

Todd Christopher Senior Managing Director, Digital & Editorial Strategy

Todd Christopher Senior Managing Director, Digital & Editorial StrategyTodd guides NPCA's publishing and content strategy and leads the team that produces our website, magazine and podcast. He is also the author of The Green Hour: A Daily Dose of Nature for Happier, Healthier, Smarter Kids.