Winter 2021

Wranglers of the West

A fully loaded mule train is a rare sight in most parts of the country, but traditional livestock packing is still thriving in Glacier National Park.

Swinging a leg over his saddle, Dave Elwood mounted Sonny, a stocky bay horse, at Packers Roost trailhead off Going-to-the-Sun Road. The string of seven mules behind him brayed and shuffled under their heavy loads of supplies. He used a squeeze of his knees to signal Sonny forward, and the train of livestock began its 3,000-foot ascent to Granite Park Chalet, a rustic mountain lodge located 4 miles away.

At a fork in the trail where Elwood led the string right, the mules’ loads brushed fluttering lime-green aspen leaves. It was June but still chilly, and the animals’ breath made white puffs in the morning air. A dramatic view of northern Montana’s austere rocky ridges unfurled as the livestock switchbacked uphill. In the valley below, the aqua-colored waters of McDonald Creek glinted through the fir and larch trees.

Elwood is the lead packer at Glacier, where he oversees 45 mules, 20 horses and five seasonal packers who work from May through October. In addition to making weekly trips to the park’s two functioning, century-old chalets with necessities such as propane tanks, toilet paper, food and tools, the packers stay busy hauling gear across the backcountry to support trail crews — their priority — as well as fire lookouts, carpenters, scientists, law enforcement, and search and rescue teams.

“We pack in everything from chainsaws to fishing nets,” explained Elwood, 62, who grew up in Montana, began shoeing racehorses as a teenager and has worked with livestock in national parks since 1999. He pushed back his mud-splattered cowboy hat and his handlebar mustache tipped into a smile. “We pack in the fish biologists, too,” he added. “I’ve learned a lot by sitting around the campfire with geologists or archaeologists over the years.”

The packers also care for the livestock and maintain the gear. That means repairing saddles, building leather harnesses, doctoring minor injuries, giving shots, checking teeth, and branding, shoeing and grooming the animals. They also teach park employees — mainly rangers — how to ride.

“We don’t have a lot of slack time,” he said with a laugh.

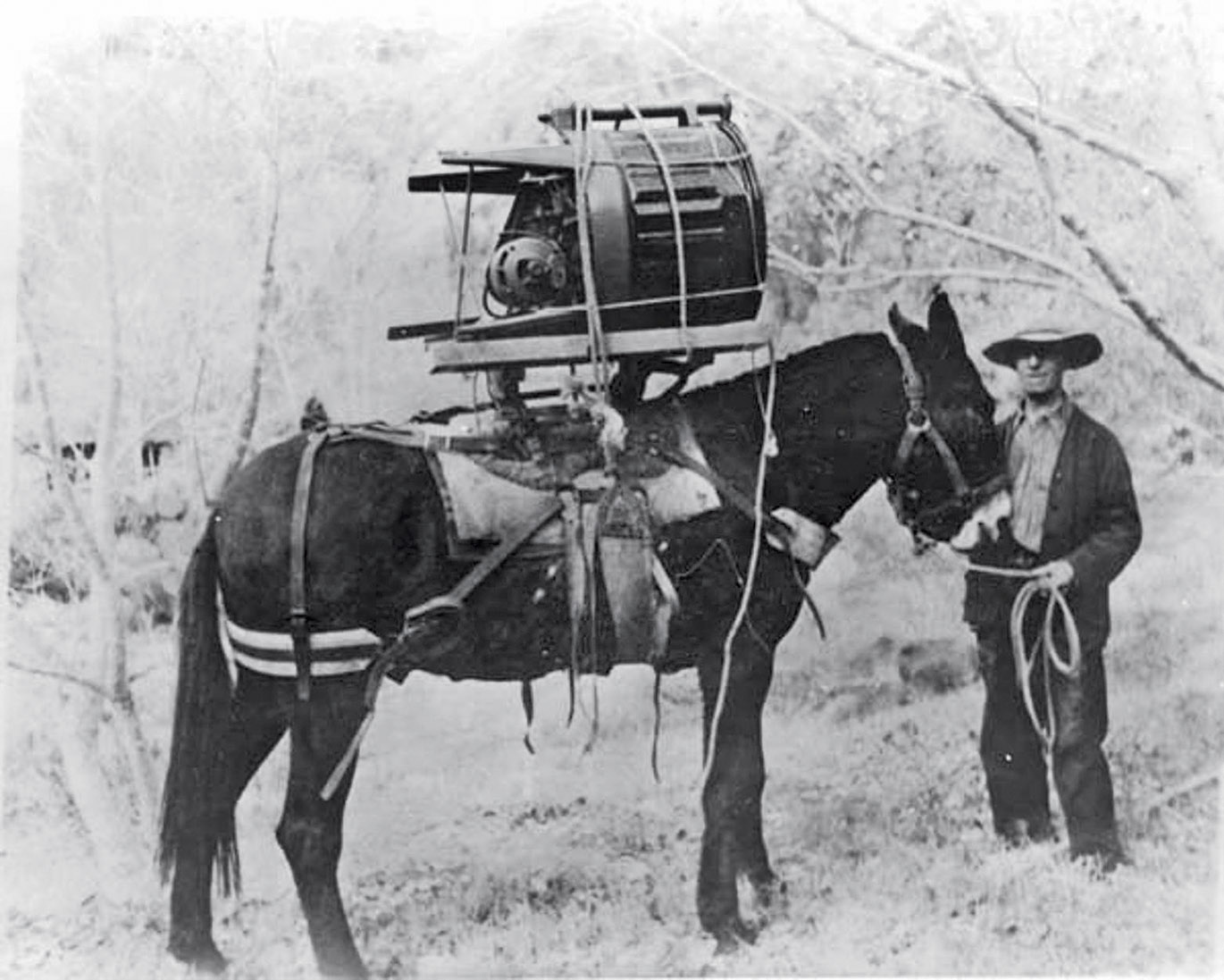

Livestock have been integral to the development and operation of many of America’s national parks since the late 1800s. Before trucks became commonplace, pack animals were the primary means for delivering supplies to build trails, lodging, bridges or outhouses. Mules and horses still play a vital role today in maintaining and building infrastructure in many Western parks where the terrain is steep, vast and roadless, including Olympic, Yosemite, Rocky Mountain and Yellowstone. Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the only Eastern park that still uses livestock for backcountry work.

A mule loaded up with a washing machine in Grand Canyon National Park in 1939. © NATURAL HISTORY ARCHIVE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTO

Packing continues to thrive in many of these Western parks because much of the land is considered wilderness — a designation spelled out in the 1964 Wilderness Act — which means motorized and mechanized vehicles are prohibited. Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks in California, for example, are almost entirely wilderness. “Livestock is the preferred method to mobilize our backcountry rangers, trail crews and researchers,” said public affairs officer Sintia Kawasaki-Yee. “We don’t see the need decreasing in the foreseeable future.”

The same goes for Glacier, where most of the park’s 1 million acres are also managed as wilderness. Dan Jacobs, Glacier’s trails program manager, explained that packers are integral to the park’s operations since roads are few and far between. The size of the livestock program has remained fairly steady — even grown slightly — over the last few decades, he said. The park has added one seasonal packer and eight animals since the mid-1980s.

“Although packing in Glacier hasn’t changed a whole lot,” said Jacobs, “what has changed is our ability to find experienced packers and stockpersons.” The pool of applicants for seasonal packer positions has shrunk, but Jacobs is proud that the park has been able to hire a younger generation of workers to “forward the long legacy of this traditional skill.”

Jill Michalak, 34, is part of that next generation. Glacier’s first female packer, Michalak started working at the park in 2017 following a two-year stint packing in Olympic. She learned to ride as a young girl in Alabama, then worked for several private outfitters in Alaska and California, where she led clients on trail rides and packed in gear for groups hunting in the wilderness. (Mules and horses play a big role in sightseeing in the West, both on and off public lands. Many national parks permit such tourist-oriented trips, but they are almost always run by concessionaires — not the National Park Service.)

Michalak answered questions about the logistics of packing as she gathered tools for a trail crew in the West Glacier Horse Barn. Long blond braid hanging over one shoulder, she efficiently bundled shovels, axes and saws into a 5-foot-long wooden box, then wrangled a thick, white canvas tarp around the package and wrapped it all up with a thick rope. This is what packers call a “manty load.” Each load weighs up to 90 pounds, and each mule carries two loads of roughly equal weight.

“There’s a standardized way of doing things, but every packer uses their own flair,” she explained.

She set aside the boxes, which would be strapped to the mules the next morning at the trailhead. Once loaded up, the animals are tied together in a line before they set out. Michalak described the importance of using a “breakaway hitch.” This allows the other mules to pull free if one falls or spooks, a common occurrence on Glacier’s steep, rocky trails.

“Mule wrecks are pretty awful to clean up,” she said. One way that packers reduce accidents is by working with the same pack string each year so they get to know each animal’s personality. “It’s kind of like being a teacher in a classroom — you know where to put each kid to get the best behavior.”

As she finished prepping manty loads, two of her colleagues who had spent the morning clearing downed trees from a nearby trail returned with their mule strings. Both young men sported mustaches, hats and dusty pants.

Trent Duty, 26, gave his mare horse a can of oats while he brushed down her sweaty coat. “I feel lucky to be here,” he said. “There aren’t too many jobs where you get paid to ride a horse and be in the mountains.”

Although it’s Duty’s first year working in Glacier, he’s no stranger to livestock. He worked for the U.S. Forest Service for six summers, packing mules into the Spotted Bear Ranger District south of Glacier. Also, he grew up around horses in a small cattle ranching community in central Montana, where he returns in the off-season to help with calving.

Next to Duty, Jacob Ellis, 30, leaned his tall, rangy body against the fence as he described typical work days, which often are 12 hours long: “We start the day at 5:30, get on the trail by 7:30 and usually come back to the barn by 4:30 for feeding time.” He said the park’s packers often travel 30 miles round trip in a day. If the destination is farther than 15 miles, they’ll spend the night.

Ellis is from Las Cruces, New Mexico, where he owns a taxidermy shop and guides hunting trips with his brother for the six months he’s not packing in Glacier. He has worked in the park for four years, and he plans to keep coming back.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›“I like the people I work with,” he said. “And I love the mules. They think differently than a horse, and they definitely have more personality.”

Elwood, returning from his trip to Granite Park Chalet, walked into the barn, stomping the dust off his boots. “I’ve always loved packing because the animals are honest,” he said. “If more people were like mules, we’d have a better world.”

He hoisted himself up to sit on a rail and took a swig of water. “We strive for high-quality work, and we’re all here because we love it,” he said. “And we’re here to do the best we can for the Park Service and these animals.”

On cue, the mules began braying from the corral, ready for dinner after a hard day’s work. The packers hopped to it, happily handing over the hay.

About the author

-

Brianna Randall Contributor

Brianna Randall ContributorBrianna Randall is a writer, communications specialist and adventurer based in Missoula, Montana. She and her family explore mountains, rivers, oceans and deserts as often as they can.