An interview with Mitch Homma, whose family members were incarcerated at Amache during World War II simply because of their Japanese ancestry.

EDITOR’S NOTE: President Biden signed the Amache National Historic Site Act in March 2022, and the site officially joined the National Park System in February 2024.

Amache is an American story. It’s a story of failure by the U.S. government to protect its own citizens. And it’s a story that resonates with current anti-immigration sentiment. Sadly, it’s also a largely forgotten story, but thanks to the work and dedication of volunteers and descendants of survivors of the Amache incarceration camp, there is now an opportunity to change this.

Shortly after the United States joined World War II, in one of the largest forced relocations in American history, the U.S. government ordered nearly all Japanese Americans living in California, Oregon, Washington, and Arizona to leave their homes. From 1942 to 1945, about 120,000 people of Japanese descent — the vast majority of them American citizens — were held as prisoners in remote military-style “camps” surrounded by barbed wire. Most of the prisoners were given just a few days to leave everything they knew and were allowed to bring only what they could carry. They had no idea where they were going or what would happen to them. Only one thing was clear: They were not welcome in their own country because they had Japanese faces and names.

After spending a few months in temporary detention centers known as assembly centers, the prisoners were forced on trains to 10 separate relocation centers. One of these was the Granada Relocation Center (better known as “Amache”), which was located in a remote corner of southeast Colorado not far from the Kansas border, on what had been Cheyenne Indian hunting grounds.

Amache spanned 10,423 acres and, at peak population, incarcerated 7,567 people in a 1-square-mile living area, which consisted of 29 blocks containing several family army-style barracks, community mess hall, public laundry and bath buildings. Most of the land was reserved for agriculture and livestock projects. Amache was the 10th largest city in Colorado during the war.

Mitch Homma.

Courtesy of Mitch HommaMitch Homma currently lives in California. Many of his relatives were incarcerated at Amache, including his great-grandparents Baptist Reverend Masahiko Wada and Kuni (nee Anazawa) Wada; his great-uncle Michihiko (Mike) Wada; his great-aunt Midori (Murai) Wada; his grandmother Mutsu (Wada) Homma; his grandfather Dr. Kyushiro Homma, who died of a heart attack at Amache when he was 44; his uncle Kunio Homma; his aunt Kumiko (Homma) Hasegawa; and his father, Hisao Homma.

Today, Mitch is helping to preserve the story of Amache and designate the site as a National Park Service unit. As NPCA advocates for Amache to become a new national park site in Colorado, we can learn from, honor and work to preserve the stories of the camp’s survivors and their descendants.

I talked to Mitch about his family’s tragic experiences before, during and after Amache and about the need to protect this important story.

Q: Growing up, did your family talk about Amache?

A: Growing up, I didn’t know anything about Amache until I was in junior high school. But even then, the only thing I knew was that it was a place where the family was sent during WWII and that Grandfather Kyushiro Homma died there in 1944. My father and his siblings never knew their grandparents, Baptist Rev. Masahiko Wada and Kuni Wada were arrested by the FBI and detained separately for several years before they were transferred to Amache. And Dad didn’t talk about Amache much until his mother died in 2004 and we found all the family’s Amache artifacts that she had saved. I learned the most about Amache when Dad was in a nursing home from 2013 to 2016, when he said that Amache took his father away. Growing up, I heard more of my family’s WWII-era stories from other church families who were also arrested and put in the incarceration centers than from my own family.

Q: Why do you think they didn’t talk about it?

A: For my great-grandparents and grandparents, I always assumed it was because of their samurai background — being a prisoner is considered extremely disgraceful and dishonorable. As community and church leaders, this would have been very difficult. The older generations really tried to shield the children from the trauma and to carry that burden for them as best they could. As for my father, I knew it was a painful reminder that his father died at Amache when he was just 44 years old (and Dad was just 8). The family lost almost everything and struggled for years afterwards. The church people really helped the family.

Q: At its peak, the number of people incarcerated at Amache reached 7,567 people, two-thirds of whom were American citizens. Unfortunately, a lot of Americans do not know this history and have little idea of what incarcerated people went through. Can you share a few details about your family’s unique background?

A: My family’s story is one of thousands of stories in this history, and a really complex one. My great-grandparents were both born into samurai families, which, in Japan, is the highest class of family next to the family of the Emperor. After graduating with a law degree from Tokyo Imperial University and then from Yokohama Baptist Theological Seminary, Great-grandfather Wada became an overseas missionary to Japan-occupied Manchuria, Korea and Russia. The Christian church roots he planted in Japan led the American Baptists to bring him to the USA. If it wasn’t for this position, he would not have been allowed into the U.S. because of the Asian Exclusion Act in 1924. Prior to WWII, he was the director of the Christian Japanese Church Federation of Southern California.

Rev. Masahiko Wada and his wife Kuni Wada, Mitch Homma’s great-grandparents, in 1933.

Courtesy of Mitch HommaAfter being trained as a nurse and teacher, Great-Grandmother Wada started several Sunday schools in Japan. In addition to Japanese, she spoke and wrote in English, German and French. In Southern California, she taught at several Japanese language schools and churches. After Pearl Harbor, both great-grandparents were arrested by the FBI. She was detained at a women’s federal detention facility in Seagoville, Texas, and Great-Grandfather Wada was sent to detention centers in Tuna Canyon, California; Santa Fe, New Mexico; Lordsburg, New Mexico; and Crystal City, Texas. Eventually they were both sent to Amache, where Great-Grandfather became a Baptist pastor at the Granada Federated Church for Block 7-H. Before the forced removal, there was a sense of panic — for example, my grandfather drained his garden koi pond at his home and burned his personal papers and belongings from Japan.

Q: What was it like for them before the war?

A: Prior to the Pearl Harbor attack, the Homma family lived pretty well and had a house in Sawtelle in Los Angeles. Grandfather Homma graduated from the University of Southern California’s dental school, and his dental practice was in Hollywood. He had several movie stars as patients, including Shirley Temple. The Hommas were pretty well integrated into the USC alumni community and Baptist church community. But even then, they faced hostilities. Under the California Alien Land Laws of 1913 and 1920, Japanese were not allowed to own agricultural land or hold long-term leases over it. Implicitly, the law was primarily directed at the Japanese. The anti-immigration and anti-Japanese sentiment was strong before, during and after the war.

Q: After Amache, did your family return to their former lives? Was that even possible?

A: The Homma family lost almost everything during WWII and their time at Amache. The dental practice, the house, most of their possessions, all gone. The Homma family followed Rev. and Mrs. Wada to Seattle after being released from Amache. Grandmother Homma, my father (who was 9 years old at the time) and siblings, also children, lived in the Seattle Japanese Baptist Church parsonage (a house right next to the actual church) for 10 years until Grandmother saved enough money to purchase a house in the Beacon Hill area of Seattle. Other families also lived in the church parsonage and church gym for several years after WWII.

There was no money for father to go to college, so he joined the U.S. Marine Corps. The family had entrusted lawyers with several thousand dollars to take care of their things during the war, but the law practice dissolved during WWII.

The Wada side of my family fared a little better in a way, because the Baptist church had stored their belongings for them and sent their possessions to Seattle after the war. Instead of the American government stepping in to help its own people after taking everything from them, it was up to organizations like the American Baptists to help instead. The family relocated to Seattle as Great-grandfather Wada became the Japanese-speaking pastor at Seattle Japanese Baptist Church. They could not return to the life that they had known in L.A. because that life was completely gone.

Another aspect of this that is less known is that, even after they were released from Amache, the government’s “Enemy Alien Control Program” was still active. This meant that my great-grandparents, who were originally arrested by the FBI, were still considered “parolees” of the U.S. government. So by no means were they free people — they were treated like criminals and had to check in with the immigration office every month long after the war ended. My great-grandparents never told Dad or his siblings about this — they must have been so embarrassed and ashamed. My father and siblings thought they were doing church business at the immigration office.

Q: About a quarter of Amache’s population were school-age children. This experience must have been traumatic for them. I remember reading that, during her pilgrimage to Amache much later in life, your aunt, who was imprisoned there as a child, reflected on how hostile the land was, that they were greeted with dust, wind and rattlesnakes. And that the day the family left Amache in 1945 she remembers the guards telling her to keep the train windows covered so as not to anger the townspeople. She must have been very confused and scared.

A: There are so many memories like that from the children at Amache. For example, prior to being transferred to Amache, my family was forced to relocate to the Santa Anita racetrack, where they lived in a horse stall. The Homma children distinctly remembered the smell of the horse stall even after it was cleaned with bleach multiple times. The stories of the children of Amache and what they experienced are some of the lesser-known ones.

Q: What are some of the other characteristics that make Amache and this history in Colorado particularly unique?

A: Amache is a very unique site in that it is closely connected to Native American history in southeast Colorado. It was built on original Cheyenne Indian hunting grounds. The Amache site was named after Amache Ochinee, the daughter of warrior sub-chief Ochinee of the Southern Cheyenne Indian tribe, whose father was killed at the massacre at Sand Creek. (Sand Creek Massacre National Historical Site now preserves this story.)

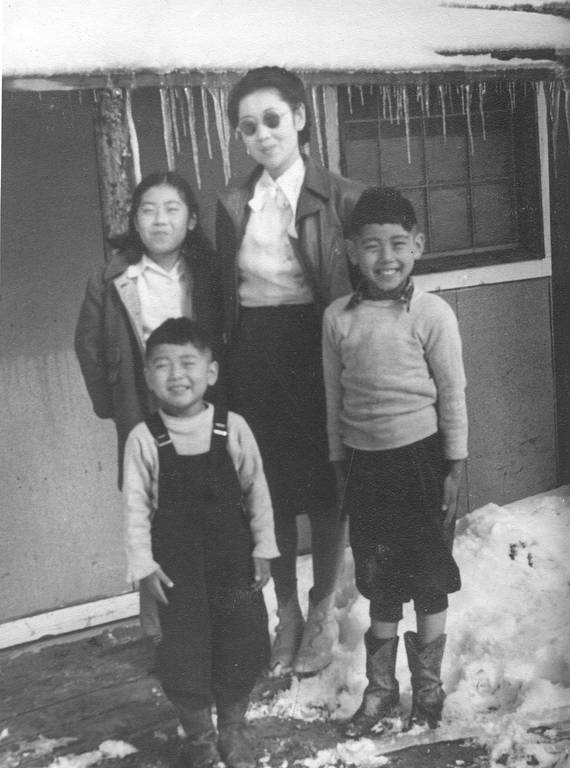

Mutsu Homma and her children Kumiko, Kunio and Hisao (Mitch Homma’s father, on the right) at Amache during the war.

Courtesy of Mitch HommaThe proximity of Amache to the town of Granada created a situation unique among the WRA camps. Walking into town and interacting with the local community was a common occurrence. An example of this interaction was how the Japanese transferred a wealth of knowledge to the locals about farming practices and many crops previously not grown in southeastern Colorado. In addition to the vegetable crops, the inmates grew field crops such as hay, alfalfa, and sorghum for the chickens, pigs, cows and other animals raised on the farmland surrounding the barracks.

It’s not as if it was always a friendly exchange, but it sometimes grew to be, and Colorado’s response to the war was very unique. Colorado’s then-Gov. Ralph Carr was the only Western governor not to bar people of Japanese descent from entering his state. And he took a public stand against the incarceration. He subsequently lost re-election and his entire political career because of this.

Other things come to mind, like the fact that a total of 953 men and women from Amache volunteered or were drafted for military service, the highest percentage of any other camp. And the fact that all of its actual foundations are, unlike a lot of the other camps, very much still intact. All of the original foundations exist, as do the original water wells, and several the trees planted by the prisoners are still standing today. You can see where the silk screen shop was located — this is where my great uncle, Michihiko “Mike” Wada, the eldest son of Great-Grandfather and Great-Grandmother Wada, worked. He was living in New York and working as an aerospace engineer when his s parents were arrested by the FBI. He returned to the West Coast exclusion zone to help the rest of the family knowing full well he would also be forced into confinement. That was an incredible sacrifice.

Q: How did you get involved in the efforts to preserve the story of Amache?

A: I got actively involved with the preservation activities at the Amache site after visiting it in 2008. Since Grandfather Homma sneaked cameras among his dental equipment into Amache and saved all the family documents, I realized that the family had an incredible amount of artifacts from this forgotten history. I volunteer with the Amache Historical Society II and help with its newsletters and website. I’ve been supporting the Amache Preservation Society and Denver University Field School and have donated many family artifacts to the Amache Museum.

Q: Why do you think it’s important to share this history?

A: Because this history and story matter. The story of World War II incarceration, and the decades of racial discrimination and government surveillance against Japanese Americans that preceded it, is still relevant. Present-day issues surrounding immigration, terrorism and the infringement of civil liberties in the name of national security echo our past. Remembering this history offers opportunities for thought-provoking discussions and raises relevant questions: How does a democracy weigh individual rights against national security? Who is considered an American?

Q: What do you hope Americans learn from this history?

A: These are valuable lessons for all Americans — citizens, immigrants and refugees. My family’s story is important since it showed how extensive the racial injustice was. It didn’t matter that my great-grandparents were Baptist missionaries brought to the U.S. by the American Baptists. Great-grandmother Wada was arrested by the FBI because she was educated and a teacher. She would never teach again after WWII. And all the Americans of Japanese descent that were incarcerated had their lives changed forever. And there are some other stories seldom told: Even though you hear a lot of negative stories, there are also some great stories of people who did stand up for the Japanese and supported the people behind barbed wire in many ways.

Amache Preserved as Part of the National Park System

NPCA helped advocate for a national park site preserving the story of Amache, where thousands of people of Japanese descent were unconstitutionally incarcerated.

See more ›Q: The National Park Service is now conducting a study to determine if Amache could be a future park site. What do you think about that?

A: I pray this happens. It will greatly help preserve the Amache site with the Amache Preservation Society and other stakeholder groups. Preservation of multiple sites is needed to tell the full history of incarceration. Many families, like mine, were dispersed among confinement sites, or moved among them at various times. There are many families, like my family, that have already contributed several artifacts and stories to try to preserve this history. My hope with the preservation of the Amache site is to educate a wider audience about this place and this history, and for America to never forget.

About the author

-

Tracy Coppola Colorado Senior Program Manager, Southwest

Tracy Coppola Colorado Senior Program Manager, SouthwestTracy Coppola is based in Denver and serves as the Colorado Senior Program Manager for the Southwest Regional Office. She is proud to have the opportunity to celebrate her state's incredible parks and advocates.