Winter 2020

'An Honest Reckoning'

Hundreds of people were once enslaved at the opulent Hampton estate, but for decades after the site became part of the National Park System, their stories remained hidden. That is changing.

First came “the Colonel” — also known as Charles Ridgely — who in 1745 purchased a tract of land just north of Baltimore, where he and his two sons founded an ironworks. After his death, his son, Charles Ridgely (“the Captain”), used the profits from the family’s businesses to build a grand mansion, which now is the core of Hampton National Historic Site. The Captain’s nephew, Charles Carnan Ridgely — later the 15th governor of Maryland — inherited the opulent family estate. “The Governor” expanded the family’s holdings to 25,000 acres, which eventually encompassed an iron furnace and forges, marble quarries, farms, and orchards.

For decades, visitors to Hampton would hear stories of these and other members of the Ridgely family. They would learn how the family amassed a fortune forging iron and selling it to the Continental Army. They would marvel over the mansion, admiring its Georgian architecture and elaborately decorated rooms. They would troop outside to see the formal gardens, the icehouse that enabled the production of ice cream in summer, and the orangery that sheltered citrus trees from Mid-Atlantic winters.

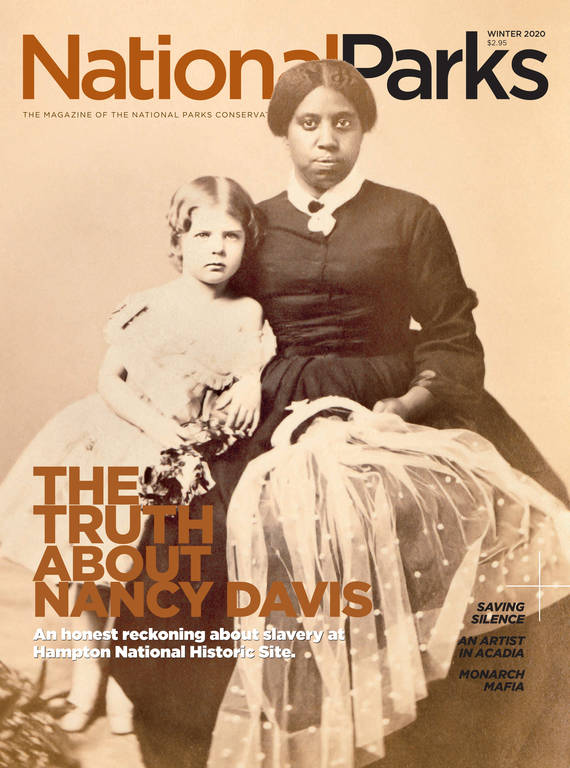

Toward the end of the tour, guides might mention Nancy Davis, explaining that she was enslaved at Hampton and chose to remain there after being granted her freedom as a young woman. The guide would pass around a copy of a circa 1863 photo of Davis, clad in black and staring at the camera, a white child leaning into her side. Davis worked as a nursemaid, raising generations of Ridgely children while never having any of her own. When she died in 1908, she was buried in the Ridgely family cemetery, the only African American person known to rest there. The subtext of the oft-repeated story was clear: Though the Ridgelys did enslave a few people, they treated them as beloved members of the family.

But that simply wasn’t true. In reality, the Ridgelys held hundreds of people in bondage, and almost every aspect of their wealth was created through forced labor. Moreover, as newspapers from the 1800s show, many of the enslaved people at Hampton fled to escape cruelty and find freedom. One escapee became the subject of a short article in an 1829 abolitionist paper from Boston. His back was marked with 37 gashes, some 3 ½ inches long and a half-inch wide, the paper reported. A member of the Ridgely family who came to claim him said “he got no more than he deserved.”

The whitewashed interpretation at Hampton led historian James Loewen to excoriate the site in his 1999 book, “Lies Across America.” The place, Loewen wrote, focused more on silverware and draperies than the human beings who had been in bondage there. But Hampton has undergone a significant transformation since Loewen penned those words. Today, following years of research, the stories of the women, men and children enslaved at Hampton are emerging from historical documents, providing glimpses of lives long forgotten. And those lives have become part of the official story of Hampton, where they are now shared with visitors through exhibits, tours and educational programs.

Change has not come easily. The work is logistically complicated and slow. Among other challenges, historical records (often just yellowed paper with hard-to-read ink scrawl) are incomplete and can be filled with inaccuracies.

The emotional barriers to studying, researching and presenting the realities of slavery are also formidable. The subject is painful for many people, and those speaking candidly about this country’s history of racism and cruelty may be met with resistance. Over the summer, online reviews of plantations in the South went viral after visitors griped about having to hear about slavery. “Would not recommend … Tour was all about how hard it was for the slaves,” one reviewer wrote.

“Let’s begin with the fact that your discomfort dictates that these things are not discussed,” said Cheryl Janifer LaRoche, an assistant research professor at University of Maryland whose three-year ethnographic study of those enslaved at Hampton was scheduled to conclude in late 2019 (but may continue). “How do we get an honest reckoning of what went on at Hampton? Many people don’t even know there was slavery in Maryland.”

A. Anokwale Anansesemfo, a ranger who has worked at the park since 2009, leads monthly tours that focus on slavery. “My name is Anokwale, which means truth,” she said at the beginning of a recent talk. “And that’s what I’m here to do, to tell you the truth. I’m here to talk about the people who were in the shadows. People who were left out of the story of this place.”

A Hampton laborer circa 1897. Hampton staff believe this is Jim Pratt, who was born enslaved at Hampton, then worked as a paid employee on the estate after emancipation.

COURTESY OF HAMPTON NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE/NPSAs Anansesemfo explained, enslaved people helped construct the Hampton mansion, which was one of the largest private homes in the United States when it was completed in 1790. They cooked the food, cared for the children and attended to the whims of the Ridgely family. They also provided the labor that sustained the family’s various business enterprises, enduring the fierce heat of the forge, plowing the fields and driving the cattle.

Once slavery ended, the Ridgely family’s fortune slowly dwindled. Faced with the steep cost of maintaining the property, John Ridgely Jr. sold the estate to a private foundation in 1947 and moved to a smaller farmhouse on the property. The mansion and grounds were given to the National Park Service, designated as a national historic site the following year and opened to the public in 1950. The day-to-day operations were managed by a local preservation group until 1979 when the Park Service took over.

Today, the site comprises 62 acres. The upscale suburban neighborhood that rings it — which used to have racially restrictive covenants — was built on what was once Ridgely family property. The all-girls Catholic school I graduated from in the late 1990s is located there.

John Ridgely, the third master of the estate, married Eliza Ridgely, a distant cousin; a copy of her portrait still hangs in the mansion. (Thomas Sully’s original 1818 painting, “Lady with a Harp,” is owned by the National Gallery of Art in Washington.)

NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART, WASHINGTON, D.C.I recall visiting the mansion with my creative writing class around 1996. We studied the portrait of long-necked Eliza Ridgely — the wife of the estate’s third owner — at the harp and peered at yellowed dolls in a child’s bedroom. Our teacher asked us to imagine we were members of the Ridgely family. I don’t remember anyone mentioning slavery. We were there to steep ourselves in the romance of a bygone age.

But then in 2007, as part of a renovation of the property, staff opened to the public several stone buildings that once had been the homes of enslaved people, eventually adding exhibits about the former inhabitants. The buildings previously had been used as storage. Hampton began adding programs and educational materials about slavery, part of a burgeoning Park Service endeavor to more fully chronicle the lives of minorities and women at national park sites.

Turkiya Lowe, the Park Service’s chief historian, said the “Holding the High Ground” initiative, launched in 2008 after a decade of planning to mark the sesquicentennial of the Civil War, inspired a host of efforts to learn about the lives of ordinary people — not just generals and political leaders — during the antebellum period. “The organization committed itself to talk about slavery as both an institution and a lived experience,” Lowe said. “The ‘big house’ narrative was no longer enough. We had to talk about how the big house was created, how it was maintained and who supported it.”

Some park sites have made significant efforts to tell the stories of racial and ethnic minorities, Lowe said. Monocacy National Battlefield in Western Maryland, for example, now preserves the history of L’Hermitage, a plantation established in the late 18th century by the Vincendière family, who eventually enslaved nearly 100 people. At the Cane River Creole National Historical Park in Louisiana, the lives of individual enslaved people and their descendants are discussed in great detail.

CHERYL JANIFER LAROCHE, an assistant research professor at University of Maryland, led a three-year ethnographic study of those who were enslaved at Hampton.

© CHIAKI KAWAJIRIHampton’s efforts to learn about enslaved people got a major boost in 2016, when the Park Service awarded the site funding for an ethnographic study. LaRoche, an anthropologist and cultural landscape specialist who studies the Underground Railroad, responded to the Park Service’s request for proposals to lead the study. “I applied because I was so disturbed and dissatisfied by the story that was being told at Hampton,” she said. “The narrative at the site was really doing a disservice to the African American history there.”

Initially, the Park Service asked for historians to trace the descendants of about 300 African Americans who were freed after the 1829 death of Charles Carnan Ridgely, the former governor. His will stipulated that women between the ages of 25 and 45 and men between the ages of 28 and 45 be freed. (Children under 2 accompanied their freed parents out of slavery. Other children and young adults remained enslaved until they turned 25 or 28, leading many to be separated from their freed parents.)

LaRoche was concerned that the initial plan for the project would “glorify” the governor and would ignore the “deeper ramifications of the history of slavery at Hampton,” she said. After she was selected to lead the study, she broadened the scope of the project to look at all those enslaved at Hampton and their descendants.

LaRoche mapped out a research plan, working with Gregory Weidman, Hampton’s curator, who has an encyclopedic knowledge of the many documents and artifacts the Ridgelys left behind. A team of nine scholars, including professors and students from nearby Towson University, began combing through historical records such as bills of sale, account books, probate inventories listing deceased people’s property, wills, diaries and memoirs. “There are literally millions of pieces of paper related to this family and the estate,” Weidman said. “It is a daunting task for any group of researchers to be able to read, view and delve into that much material.”

Another particularly challenging aspect of the project was tracing the lives of women, since many enslaved women were referred to by only their first names, their parents’ names or nicknames such as “Sam’s Millie.” Others had common last names that were hard to trace. The researchers compared records of Christmas presents the Ridgelys had given the enslaved children, manumission lists, city directories, cemetery records and census records. They pored over online genealogical charts from sites such as Ancestry.com, studied oral histories of nearby African American communities and reached out directly to elders in those places.

One of the first families the team was able to trace was that of George Batty, who was emancipated after Gov. Ridgely’s death, along with his wife and daughters. A fellow researcher directed LaRoche to Batty’s great-great-great-great-granddaughter, Myra “Neicy” DeShields-Moulton, a retired computer engineer who lives in York, Pennsylvania, about an hour north of Hampton. After the Civil War, several of Batty’s descendants settled in York, where they found work in metal foundries, DeShields-Moulton said.

Visitors inspect a replica of a bullwhip.

© CHIAKI KAWAJIRIDeShields-Moulton said she knew almost nothing about her family history until she began to explore genealogy about a decade ago. LaRoche’s team enabled her to better understand her origins and to put them in perspective, she said.

“It can be very difficult for African Americans to be proud of where we came from because a lot of us have no idea,” she said. “There are so many stories that have been told that are not correct.” DeShields-Moulton visited Hampton last year for a symposium on the ethnographic study. It was painful to think of her ancestors suffering there, she said, but ultimately it was a hopeful experience to learn about her roots. “Look where we are now,” she said. “We’re thriving. We have doctors, lawyers, professional athletes, people who have persevered despite the long odds against them.”

The research helped Rick Cummings, a retired city manager of Camden, New Jersey, solve a mystery that had long puzzled his family: They knew almost nothing about a man named Henry Cummings, a key figure near the top of an elaborate family tree his mother had made. After Weidman traced the family lineage, LaRoche contacted Rick Cummings. She explained that Henry Cummings (also spelled Cummins) had been enslaved by Gov. Ridgely and lived at the Ridgely-owned White Marsh plantation. After he was freed, he worked as a chef in Baltimore and became known for his terrapin soup, a local delicacy of the era.

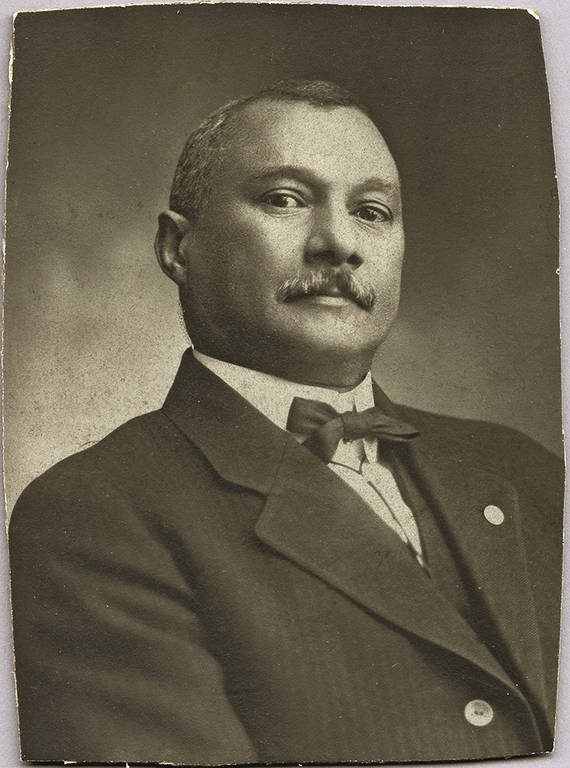

Harry Sythe Cummings, whose father was enslaved at a Ridgely-owned plantation, was one of the first two black graduates of the University of Maryland’s School of Law and the first black member of the Baltimore City Council.

HARRY SYTHE CUMMINGS PHOTOGRAPH COLLECTION/MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETYHenry Cummings and his wife, nee Eliza Jane Davage, managed to send all but one of their children to college, a remarkable achievement, Rick Cummings said. One of the couple’s sons, Harry Sythe Cummings, became one of the first two black graduates of the University of Maryland’s School of Law in 1889. He was also the first black member of the Baltimore City Council.

“I’m really indebted to the Park Service and Dr. LaRoche,” said Rick Cummings. “I’ve had the realization that I hadn’t paid much attention to the daily lives of my ancestors. I’m realizing now how much they accomplished during their lifetimes and what a substantial contribution they made to their country and their community. To think they were able to survive all that and then pass along values to their children that have been handed down through to the current generation — education, perseverance, tenacity.”

The new findings continue to roll in — “it’s snowballed,” Weidman said — and the staff at Hampton is doing their best to keep up. Rangers and volunteers have been attending trainings about how to have difficult conversations about slavery and how to share the newly discovered information.

Ranger Anansesemfo, who is also the president of the Griot Society of Maryland and an adjunct history professor, weaves vivid stories from Weidman and LaRoche’s research into her talk. She often tells the story of Lucy Jackson, who was pregnant with her first child when she arrived at Hampton in 1838. The Ridgelys had purchased her for $400. Jackson rose to become the mansion’s head housekeeper and, along the way, acquired a wardrobe of fine clothes her free husband bought her. In 1861, at the dawn of the Civil War, Jackson’s eldest son escaped from Hampton, and Jackson followed a couple years later. After the war ended, she hired a Washington lawyer to write to the Ridgelys to demand that the clothes she had left behind, her petticoats and fur muffs, be returned to her. (The family wrote back that her clothing had already been seized by the other “servants.”)

This photograph of Nancy Davis and Eliza Ridgely III was taken in a Baltimore studio around 1863, after Davis, who was born into slavery, had been freed.

COURTESY OF HAMPTON NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE/NPSLike previous generations of guides at Hampton, Anansesemfo shares Nancy Davis’ portrait. But she challenges visitors to think about her life through a different lens. Davis was 5 when her mother was granted her freedom, following Charles Carnan Ridgely’s edict that allowed men and women to be manumitted in their 20s. Her parents moved to a nearby farm, leaving behind Davis, who would be forced to remain in bondage for two more decades. Anansesemfo asks: Did she feel abandoned? Did she remain with the Ridgelys after the Civil War because she was attached to the family or for another reason? Was it because she could not conceive of another life?

Anansesemfo’s tours are solemn. Both times I participated, the group was mostly white, although several people of color attended. Natalie White, a teacher from a nearby suburb, said she and her husband brought their three children on the tour to broach the subject of slavery. “I wanted to introduce them to what we went through,” said White, who is black.

Laura Holbrook, a white writer from Washington, D.C., said she visited Hampton as part of a pilgrimage of sorts to sites where people had been enslaved. “No one talked about slavery when I was growing up,” she said. “It’s so important to hear the truth about what went on here and to be honest about it.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›One of the most exciting moments of the ethnographic study came this past summer when LaRoche and Weidman connected with a living relative of Nancy Davis. Charles Brown, 76, a retired cab driver, found LaRoche’s team through a friend who had heard of the study. Brown had grown up hearing his great-grandmother (who was born around 1877 and lived to 110) talk about the family’s roots on the Hampton plantation, where she lived as a child. She told stories of “Aunt Nancy” — and mentioned that their forebear was buried among the Ridgelys.

Brown was raised in the close-knit African American community of East Towson. Many enslaved people from Hampton moved to the town after being freed, and some of their descendants still live there today. “That’s where most people in the neighborhood were from” a century ago, he said. “That was common knowledge.” Brown has a deep understanding of ties among community members and walked LaRoche through the family trees of many descendants of those enslaved at Hampton.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

For LaRoche, Brown’s understanding of these relationships is a reminder of just how recently slavery existed and how it still shapes communities today. The significance of these findings is huge, she said. “We’re seeing interconnections among all of these people with ties to Hampton. This is living memory. We can touch this now.”

About the author

-

Julie Scharper Contributor

Julie Scharper ContributorJulie Scharper is a freelance writer and journalism professor in Baltimore, Maryland.