Summer 2019

Open Roads & Endless Skies

At Great Basin National Park, a father and son gaze at stars, touch ancient trees, and reflect on space, time and the universe.

Comet Swift-Tuttle, a mass of rock and ice some 16 miles across, hurtles obliquely through the solar system, passing by Earth every 133 years. There’s no cause for alarm anytime soon, but in 4479 the comet will come quite close to us, astronomically speaking; at some point in the future, its orbit might even put it on a collision course with our small blue planet.

In the meantime, we have this occasional passerby to thank for the annual celestial display we know as the Perseid meteor shower. Every August, as Earth moves through Swift-Tuttle’s trail of debris, grains of rock and dust enter the atmosphere at dizzying speeds and burn up — sometimes spectacularly — becoming shooting stars that streak across the sky. Where there are clear dark skies, as many as 100 per hour can be seen on the night of the meteor shower’s peak. It’s a wonderful sight.

Catching the Perseids always was a highlight of my childhood summers, but it had been quite a while since I’d seen them. Rain, moonlight and even a new parent’s desperate need for sleep all have conspired against me over the years. But with the peak of this past year’s shower falling over a moonless weekend, I resolved to be somewhere known for dark skies and decided to venture to Nevada’s Great Basin National Park.

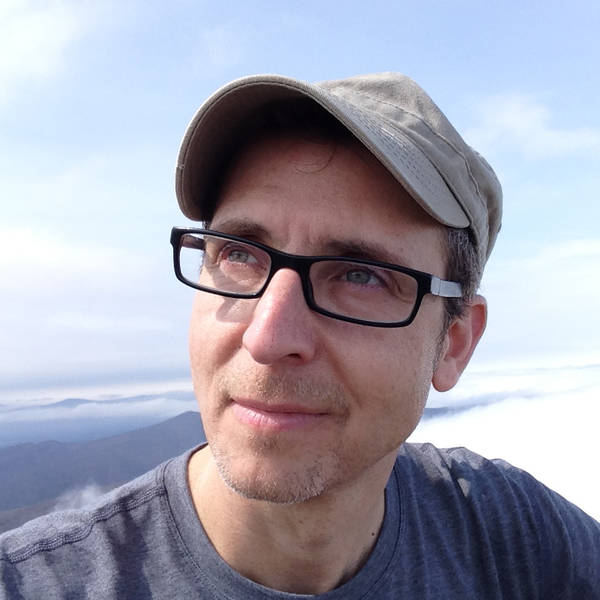

The author and his son on the Wheeler Peak Trail

© TODD CHRISTOPHERIn truth, I had another motive. I invited my son, Elijah, to join me, knowing he wouldn’t be able to resist an adventure in a park we hadn’t yet been to, especially one where starry nights and ancient bristlecone pines beckoned. And this spirited boy — a nature-loving kid who as a toddler would gently pet the bumblebees drawn to our flower beds — was somehow just weeks away from his senior year of high school. Time was flying, and if we didn’t steal a little for a father-son outing now, who knows when we’d next have the chance?

So it was that we found ourselves among the 250 visitors gathered on blankets and camp chairs in front of the Lehman Caves Visitor Center on the evening of the Perseids’ peak. As twilight set in, Mars and a scattering of stars shone brightly, peeking through the gaps in the gathering clouds. Hopeful rangers set up a row of telescopes for viewing planets and deep-sky objects. We were in for a terrific evening — so long as the weather held.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

Great Basin owes its famously dark night skies to its isolation, elevation and high-desert climate. With little humidity and almost no light pollution to contend with, visitors are treated to some of the country’s clearest night skies, and in 2016, the International Dark-Sky Association officially recognized Great Basin with an International Dark Sky Park designation. Tyler Nordgren, the astronomer and night sky ambassador who coined the slogan “half the park is after dark,” recommended Great Basin for dark-sky status, citing its views of the Milky Way, which he described as the finest he had experienced anywhere in the National Park System.

“The parks, as they protect the scenic wonders of our country, have almost as an accident preserved our views of the sky overhead at night,” he told me in an email. “The Milky Way is a scenic splendor that almost everyone everywhere used to share, but now almost no one sees anymore.”

The certification is not just for Great Basin’s natural darkness, but for the park’s efforts to preserve and promote it as well. At the visitor center, staff have fitted light fixtures with dim red bulbs that won’t interfere with an observer’s night vision. The park is also home to the first research-grade observatory in the park system, with a remotely operated, 28-inch telescope used by university students and faculty conducting research on planets outside the solar system. And Great Basin hosts a rich slate of educational programs, including an annual three-day astronomy festival, monthly full-moon hikes and special events such as the Perseid viewing party.

NPCA at 100

“In the last 10 years or so, the interest in astronomy among the general public has really gone through the roof,” said Becky Gillette, a seasonal ranger at the park. “I regularly interact with visitors who say that’s why they came — they want to see the stars, they want to see the Milky Way, they want to start learning a little bit more about the universe.”

Though Great Basin remains one of the least-visited national parks, its annual visitation has roughly doubled over the past decade — surpassing 150,000 for the first time in 2017 — thanks in part to its nightlife. The park’s astronomy programs now welcome nearly 10,000 visitors a year.

“We even had 70 people show up here for an astronomy program during an active rainstorm,” Gillette said. “Like, it’s raining — not just overcast. That says a lot.”

While it wasn’t raining for Elijah and me, it increasingly looked like our luck was running out. By the time the skies had fully darkened, the remaining patches of clear sky had all but disappeared, and the forecast was not promising.

“Sorry, folks,” Gillette said over a compact PA system. “We put in a call for clear skies, but it looks like the clouds have other plans.”

The crowd dispersed. Blankets were gathered, camp chairs folded, telescopes packed away. We all were reminded that even where the skies are darkest, visibility isn’t guaranteed.

I was disappointed, but the night skies were only part of what drew me to Great Basin. The more pressing reason to go was the promise of being together with Elijah in the middle of nowhere for a while. Besides the usual pressures of work and school, of parenting and being a teenager, we were on the verge of a hectic and uncertain time — his college applications lay just around the corner — and the idea of reconnecting in a place of peace and beauty, even briefly, was appealing. If getting there meant long drives on open roads under endless skies, all the better.

Perhaps fittingly, our trip began under a bit of a cloud — first figuratively in D.C., where catching our early-morning flight was made more challenging by our differing interpretations of Elijah’s curfew the night before, then literally in Salt Lake City, where we landed amid thick haze from wildfires ravaging California. We stocked up on food and water and headed west in the rental car; I drove while Elijah dozed. We gradually gained elevation the whole way, and as we did, the haze lifted. By our first stop to refuel and rehydrate — at Utah’s Bonneville Salt Flats, a vast salt pan swarming with hot rods and happy gearheads there for the famed speedway — the sun shone bright, and the temperature hovered around 100 degrees.

We drove on for two more hours through the lonely, undulating heart of the Northern Basin and Range Province, along unbroken stretches of road where we saw more wild horses than other cars. Beautiful landscapes soften hard feelings, and we put the shaky start behind us; we talked, laughed and listened to music, lulled by the rhythm of the road and the steady presence of the low ranges to either side. We were hungry and tired when we finally reached our lodging in the historic railroad town of Ely, Nevada, the self-described gateway to Great Basin National Park, some 66 miles away. There were closer options — Baker, Nevada (population 68) as well as the park’s first-come, first-served rustic campgrounds — but those places have far fewer amenities, and what’s one more hour on roads like these?

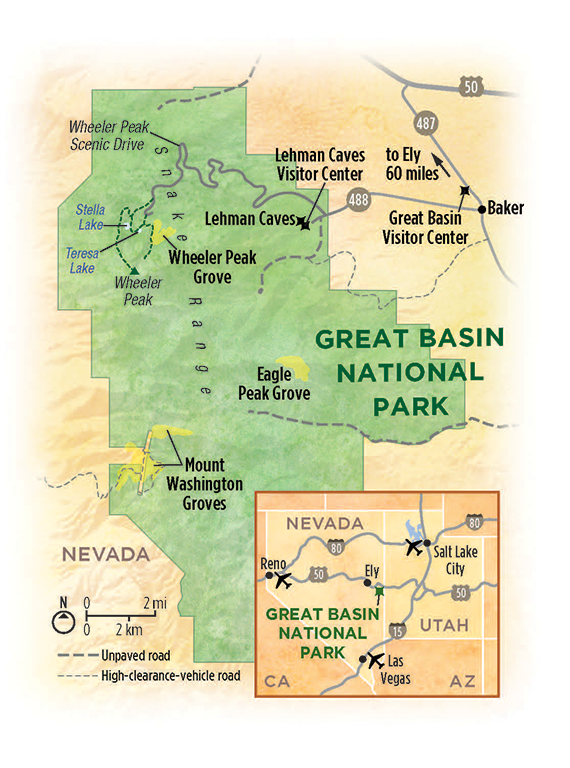

We headed out the next morning in mixed sun and clouds, eager to explore. Stretching across 77,180 acres, the park comprises elevations ranging from 5,000 feet to more than 13,000 feet and preserves a remarkably diverse high-desert landscape, from sagebrush steppe to limestone caves to alpine peaks and meadows. While we were excited by the prospect of dark skies and meteors later that evening, our aim for the day was to see some earthbound wonders: Great Basin’s bristlecone pines.

We rolled along the long, rising entrance road — stopping to admire the rusted frame of an antique car standing like an art installation in the brush — and after grabbing a park map at the Lehman Caves Visitor Center, we headed to the trailhead. I guided the car up the winding 4,000-foot climb that is Wheeler Peak Scenic Drive, navigating its 12 miles of hairpins and switchbacks while Elijah took in the stunning views of peaks above and Snake Valley below. By the time we parked at 10,000 feet, sagebrush had given way to pine, fir and aspen, and it felt as if we’d entered an entirely different park altogether.

I had barely shouldered my pack before Elijah bounded down the trail, but I was quite used to trying to keep pace with him. As soon as he could stand, he could run, and he hasn’t slowed down much since. As a hyperactive toddler, being outdoors and in motion could always calm him — and even now, nature is his balm.

The air was crisp and sweetly scented, and before long, the trail carried us through a thick grove of quaking aspen. We wandered across a sloping sub-alpine meadow buzzing with the electric sounds of grasshoppers before coming upon one of Great Basin’s star attractions, Stella Lake. Wreathed by conifers, the lake is a glacial tarn lying in the shadow of Wheeler Peak, the park’s highest point at 13,063 feet. We’d had the trail mostly to ourselves until then, but a few other visitors were enjoying the view here, too — some skipping stones across the still, blue-green water.

A mile and a half later, after passing Teresa Lake and following the rising trail through a stand of limber pine, we finally found ourselves just below the tree line among some of the oldest living things on the planet — dozens of ancient bristlecone pines growing amid the quartzite boulders and glacial debris beneath Wheeler Peak. It is near this grove that a tree dubbed Prometheus was accidentally felled in 1964 — the accounts vary, but all end tragically — and revealed to be some 4,900 years of age, making it the oldest known single organism at the time. It’s impossible to know for sure, but we were likely standing among at least one tree that took root as the Pyramid of Cheops was being built.

Metal signs along the short interpretive trail explained the bristlecones’ ability to endure the isolation and harsh conditions of their high-elevation habitat. That capacity is the result of slow growth that yields a dense, durable wood. It is, in fact, the trees that withstand the most unforgiving conditions that live epically long lives and take on the wild, fantastic shapes the species is known for. One sign mentioned the bristlecones’ “grotesque” beauty, a word now barely visible, scratched away by visitors making an understandable if forbidden editorial statement. Elijah was drawn to one tree in particular and stood for a long moment with his hand pressed against its weathered trunk, as if feeling the weight of the centuries — maybe the millennia — it had seen.

It was a strangely comforting place to be. We lingered for a while in silence before finally turning back.

Clouds darkened as we climbed back down, but as we reached Stella Lake again, the sun broke through for what would be the last time that day. This time, we had the lake all to ourselves. I rummaged through my pack for a granola bar and was startled by the sound of splashing. I looked up to find that Elijah had waded out into the snowmelt for a brief but invigorating dip in the cold, clear water.

I laughed out loud but wasn’t surprised. Baptism by fire — or icy water — was nothing new to Elijah. He had always plunged headfirst, if not headlong, into life and surely always will. At times, his spirit has caused me a bit of worry, but his joy has always been more than worth it, and at that moment, he was having a blast. If he had a care in the world since we’d arrived, I certainly hadn’t noticed.

We doubled back in the late-day light and drove to the visitor center, heading straight to a true oasis in the desert: the cafe serving diner-style breakfast, lunch and soft serve ice cream in a space with a view that stretched all the way to Utah’s Confusion Range. We arrived just before closing, in time for pretzel-bread sandwiches, salads and fries capped by root beer floats, and afterward — surprised to find that we had cell service — made an Instagram post or two.

We enjoyed the cafe so much that we had both breakfast and dinner there the following day. Overcast skies and periods of rain dampened the landscape, but, unfazed, we returned to the trails of the Wheeler Peak area for a few hours. There, the aspen groves teemed with hundreds of watchful “eyes” — the distinctive black scars left behind when the trees drop their lower branches — that seemed to follow us as we walked. We briefly considered tackling Wheeler Peak itself, but the exposed ridgeline is no place to be when the weather is threatening, and we’d already heard the occasional rumbling of thunder. By the time we headed back to the visitor center, the day was threatening to be a washout.

Luckily, we had picked the right day for a one-hour tour of Lehman Caves, a quarter-mile-long cavern that was first protected as Lehman Caves National Monument in 1922. Led by a ranger through the labyrinth of subterranean chambers, we marveled at the limestone formations and were struck by the capacity of some broken stalactites to reform — to say slowly would be an understatement — from narrow growths called soda straws. When our guide switched off the lights, we experienced the sensation of standing in complete, disorienting blackness, hearing only the sound of muffled breaths.

360 Video by Todd Christopher (click to move around)

The gray skies brought an early twilight, but we left the park in good cheer. The weather hadn’t completely cooperated, but we’d had two days full of wonders great and small. Elijah, who has joined me on many trails from Shenandoah to Death Valley, decided the previous day’s hike might have been his all-time favorite. “Time and space feel different here,” he said.

How could I disagree? In this ancient place, time felt abundant. And, amid the vastness, contemplating the inevitable spaces that will grow between us as Elijah comes into his own somehow seemed less daunting. That is to say: It felt like it would all be OK.

I’d had the same feeling the previous night, after the ill-fated viewing party, when we’d driven off in the darkness toward Baker and the 60-mile stretch of two-lane highway that would take us back to Ely. Along the way, Elijah kept one hopeful eye on the skies through the moonroof and played songs from his iPhone on the car stereo, picking one of my old favorites (David Bowie, Supertramp) for each new one of his (Rex Orange County, Tame Impala). And then, somewhere in the nameless gap between the Snake and Schell Creek Ranges — and when we’d all but given up hope — the clouds gave way, just a bit, to an inky night sky.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Spotting a dirt road, we turned off, parked and hopped out of the car. Overhead, banks of cloud sailed by, but an opening had appeared between them and was widening, granting us a view of perhaps a quarter of the sky. It was enough. We scrambled onto the trunk of the car, reclining with our backs against the glass, and looked up into the night. As our eyes adjusted to the darkness, we could see not only the stars of summer constellations but also — faintly at first, then unmistakably — the gossamer band of the Milky Way. It had been a long time since either of us had seen it.

It wasn’t the best view of the firmament, but that didn’t matter. For some time — 20 minutes? 30? An hour? — we lay there together in the middle of nowhere until one lonely Perseid meteor streaked across the sky, reassuring us that the cosmos, at least for now, was unfolding according to plan.

About the author

-

Todd Christopher Senior Managing Director, Digital & Editorial Strategy

Todd Christopher Senior Managing Director, Digital & Editorial StrategyTodd guides NPCA's publishing and content strategy and leads the team that produces our website, magazine, books and podcast. He is also the author of The Green Hour: A Daily Dose of Nature for Happier, Healthier, Smarter Kids.