The paradox of how 10 square miles between Maryland and Virginia became the nation’s capital — through a culture of slavery and a coincidence of geography

On every visit to Washington, D.C., I come to this river, the Potomac. Near where I stay, a path follows Foundry Branch in Glover-Archbold Park, a tiny tributary that winds through woods of sycamore and beech, tulip poplar and oak, to its mouth. I often walk this forested corridor within the city, at last passing through a dripping, rock-walled tunnel under the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal to reach the river’s edge.

Trace: Memory, History, Race and the American Landscape

This story is adapted from Lauret Savoy’s 2015 book, “Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape.”

See more ›Here in the District of Columbia, by the banks of this river, millions of touring travelers come each year to visit some of the most celebrated parklands and memorials honoring presidents, visionaries and veterans who helped shape this country. Indeed, one can explore the cultural and natural histories of this region in National Park Service holdings in and around the city.

Yet the Potomac has carried what some call the freight of history on its back. I am part of the river’s load. Both my parents are buried in Washington. And I, though not born here, realize I exist because of this river, this city and how it came to be.

The paradox that is our nation’s capital struck me as from a blow on Jan. 20, 2009. That day nearly 2 million people gathered on the National Mall to witness Sen. Barack Obama become the 44th president of the United States, the first African American in this office. My friend Kris and I were among them. This crowd differed in character and tone from all I’d known. Young parents carried toddlers in backpacks. Elderly walked with youth. Well-dressed affluence shared sidewalks with many more of poorer means. Strangers nodded and spoke to each other with kindness. I overheard a young woman lean down to tell the child whose hand she held, “Remember this day and be proud of who you are.” Children of nearly every continent stood together.

It was then that I saw with a new clarity how Washington, D.C., is an invented place. For unlike capitals of most other nations, the District began far from the country’s economic, intellectual or cultural centers. Its origins arose instead from a political deal.

Public history tends to present the founding of the city in these terms: The Constitution authorized a district of up to 10 square miles as the permanent seat of the new federal government. In July 1790, Congress passed the Residence Act, empowering President George Washington to choose a site along an 80-mile stretch of the Potomac River to replace Philadelphia as capital.

Yet public history often fails to mention the backstory, the why behind this geography. Put simply, the first president wanted the capital embedded in the South, not too distant from his Virginia plantation. It was inconvenient for a president who depended on enslaved workers — or any federal official in similar circumstances — to live in his desired and accustomed manner in a region antagonistic to it. With its Quaker heritage, Philadelphia was long known for abolitionist sentiments. A new law automatically emancipated any enslaved person brought into Pennsylvania for more than six months. The permanent home for the federal government, in George Washington’s mind, had to be located where slavery would remain unmolested.

The capital’s placement also came down to the fall line, where the Potomac River leaves its rockbound channel to meander across the coastal plain as a broad tidewater arm of Chesapeake Bay. Here is the farthest inland reach of the sea, the head of navigation for ocean-going vessels. By tracing the fall line across rivers from Alabama to New Jersey, one can see the long line of settlements begun at a time when the power of moving water drove industry, and sailing ships were tools of commerce and war.

George Washington’s plantation lay just downstream along the Potomac. He hoped canals and overland roads would make the river an artery of commerce connecting the western interior — “the Ohio countrie” beyond the mountains — and the transatlantic world. Yet the new president stood somewhat in the background as his secretary of state and the leader of the House of Representatives, fellow Virginians Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, negotiated this plan with Secretary of the Treasury Alexander Hamilton.

Thus, in July of 1790, Congress voted by a narrow margin to move the capital. Vice President John Adams suggested that the value of the president’s land had jumped “a thousand percent.”

The first federal census, taken the same year, counted more than half of the new nation’s nearly 700,000 souls held in bondage in just Virginia and Maryland. Of all free African Americans, more than one-third lived in these two states.

My father’s ancestors, my ancestors, have long inhabited this scene. My hope is that, in relating its history, I might come nearer to ghosts.

Early 19th-century visitors to the city of Washington were often surprised. They found abandoned projects and partly built structures, shacks and stately manor houses scattered between fields and woods. The President’s House (later called the White House) was built on David Burnes’ tobacco plantation. The Capitol rose on an estate owned by Daniel Carroll. Goose or Tiber Creek flowed where Constitution Avenue now runs, emptying into the Potomac River where the monument grounds now lie. Roads were muddy or dusty depending on the weather. Congress supposedly met between the harvest and next season’s planting, to avoid sweltering summers with insect- and water-borne diseases. Resignations and proposals to move the capital to a more hospitable location were proffered year after year after year.

“It is sometimes called the City of Magnificent Distances, but it might with greater propriety be termed the City of Magnificent Intentions,” a young Charles Dickens observed on his 1842 visit. “Spacious avenues, that begin in nothing and lead nowhere; streets, mile-long, that want only houses, roads, and inhabitants; public buildings that need but a public to be complete; and ornaments of great thoroughfares, which only lack great thoroughfares to ornament — are its leading features.” Decades after it began, Washington hadn’t yet arrived.

The Land Beyond Hate

One woman’s journey to uncover her history and other missing stories of the American landscape

See more ›Around the nation’s centennial, Frederick Douglass recalled with great sorrow that the capital’s placement “was one of the greatest mistakes made by the fathers of the Republic,” a mistake that “contained the seeds of civil war and disunion.” For “sandwiched between two of the oldest slave states, each of which was a nursery and a hot-bed of slavery; surrounded by a people accustomed to look upon the youthful members of a colored man’s family as a part of the annual crop for the market; pervaded by the manners, morals, politics, and religion peculiar to a slaveholding community, the inhabitants of the National Capital were, from first to last, frantically and fanatically sectional. It was southern in all its sympathies and national only in name.”

The District of Columbia was embedded where indentured and enslaved laborers had for two centuries brought the tidewater plain under cultivation. So perhaps it’s no surprise that Congress initially adopted for it the laws of Maryland and Virginia, accepting a colonial act that “all Negroes and other Slaves already Imported or hereafter to be Imported into this Province, and all Children now born or hereafter to be born of such Negroes and Slaves shall be Slaves during their natural lives.” Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, Andrew Jackson, John Tyler, James K. Polk and Zachary Taylor staffed the White House with enslaved servants during their presidencies. Slavery would thread the District’s daily business until the second year of the Civil War.

African Americans, including my father’s people, accounted for roughly a quarter to one-third of the city’s population at the turn of the 19th century. Those enslaved at that time outnumbered free five to one.

Acknowledged or not, the hands, strength and skills of “Negro hire” fashioned building materials from outcrop and woods, from sand and mud, and then, after clearing sites, constructed the capital city over decades. It may never be possible to know how many helped erect the iconic structures so visible on inauguration days, including the Capitol and President’s House. Two centuries would pass before Congress publicly acknowledged these builders.

A few years ago I confided to my cousin Cissie my longing to know of origins. Of who we were to each other. Of who we were to these tidewater and Piedmont lands. I wanted to find a tangible thread that would place me, explain me in time and space. I had little else to grasp.

Cissie introduced me to Buddy, another cousin who had traced the Savoy line to our great-great-great-grandmother Eliza. She appears in paper records because she lived in the home of Timothy Winn, a man who controlled contracting and procurement for the Washington Navy Yard when it might have been the city’s largest employer early in the 1800s. Buddy invited me along to search through Winn’s estate documents in the National Archives. What I remember most of our visit is the smell.

Fifty Years Later: Wilderness & Civil Rights in the Same Breath

This summer marks the 50-year anniversary of two landmark pieces of legislation—the Civil Rights Act and the Wilderness Act—that are linked more closely than they might seem.

See more ›Once opened, the archival box released the mustiness of age. Our white gloves picked up a fine gray-tan dust as we gently handled page after page. Along with parcels of land, a house and household items of a learned, traveled and comfortably situated man — carpeting, silver, mahogany sideboards, desks, library cases — Winn’s personal estate included various stocks, globes of the world, a large New Map of the United States by Mitchell, and copies of both the Declaration of Independence and Washington’s Farewell Address set in gilded frames. She appeared in the third to last entry on the last page of an inventory valued at $16,824.37. “Eliza Savoy $300.”

The quiet of that room caught my breath. Our great-great-great-grandmother was inked in by name as property of a dead man, to be disposed of by the terms of his will.

The will wasn’t what we expected, if I could admit to having any expectation. Timothy Winn had made a special provision for “my Servant Woman Lizy, or Eliza Savoy” and two sons. She and another aging man were never “to be sold, nor be set free on any account whatever. I have too much regard for them to set them free to provide for & support themselves in their old age, after having had their faithful services for the best part of their lives. They must be comfortably & well provided for & kindly treated & supported & receive every indulgence compatible with their situation.”

Of Eliza’s “situation” we imagined a great deal. Of her origins and her fate we still know little. Nor do we yet know the father of her boys, though we have suspicions. Eliza’s son Edward and his young wife Elizabeth Butler Savoy appear in the 1850 and 1860 censuses in Washington City as free “mulattoes.”

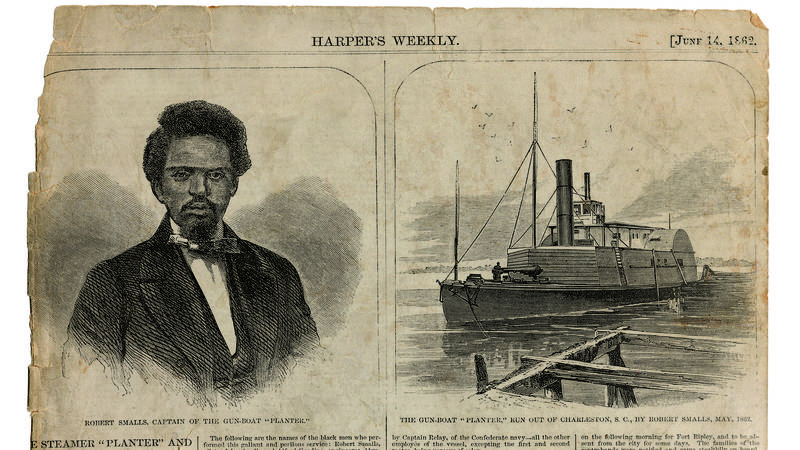

By the early 1800s, the nation’s capital had become what abolitionists and later historians referred to as “the very seat and center of the slave trade.” Members of the House and Senate often saw traffickers from their windows, driving chained and handcuffed men, women and children by the tip of a whip. Even freeborn African Americans risked being kidnapped as “runaways.”

Vestiges of slavery’s landscapes and architecture lie in plain sight. One can still see outbuildings next to stately residences scattered across the city that had served as quarters. But the markets and holding pens are long gone. Some of the most notorious ones had stood near the National Mall, where some of the most revered monuments and memorials now stand — where so many would come for Barack Obama’s inaugurations.

Little remains of the antebellum landscapes of free people of color. Their growing presence so alarmed mayors and city councils that the first of a series of Black Codes was enacted in 1808, shortly after the capital opened for business. Designed to limit the movement of all African Americans, the codes also aimed to check “unruly slaves” through enforced curfews and public conduct rules. A pass was needed to move about after 10 p.m. Dances and parties required permits. Alcohol couldn’t be purchased after nightfall. Intermarriage between “colored persons and white persons” held dire penalties. Suffrage was out of the question. Anything to abate what many white citizens perceived as a threat: If free people of color could enjoy “privileges” in the capital denied them elsewhere in the South, who knew when the floodgates could be closed!

Code amendments called for “free colored persons” to register with the city government and carry certificates of freedom at all times or be subject to arrest or capture as runaways. Soon they had to present to the mayor, in person, not only papers of freedom but also vouchers signed by white citizens guaranteeing their good character and solvency. They had to post substantial “peace bonds.” Then Congress barred all African Americans from the Capitol grounds unless there on official business. Segregation ruled in death as well as life, as burial grounds separated mortal remains by race.

Even stricter codes weren’t severe enough to keep free men and women of color from seeking refuge within the capital city. By 1830 more free than enslaved lived here. And the work they did was needed. As domestic servants, waiters and cooks, carpenters, bricklayers, oystermen, blacksmiths, washerwomen, hackmen and carters, livery-stable hands, shoemakers and tailors, messengers, general laborers. This list goes on.

Though the city council continued tinkering with the codes, nearly one-third of the District’s inhabitants were people of color by the mid-1840s. Most of them, more than 13,000, were free. Months before the opening volleys at Fort Sumter, the 1860 census would count 5 percent of the nation’s African American population as free. Those living free in Washington outnumbered those in bondage by nearly four to one.

To know that ancestors inhabited this history and this place yet to find little of their lives gnaws, a deep hunger. The 1860 Federal Census lists my great-great-grandfather Edward Savoy as a “laborer,” my great-great-grandmother Elizabeth a “washerwoman.”

Neither slavery nor the business of human trafficking existed easily in the nation’s capital. Abolitionists petitioned Congress repeatedly. Even members of the city council who held people in bondage protested the District trade because too much of the “merchandise” was handled by nonresident dealers who took profits out of the city. Only in April of 1862, as the Civil War entered its second year, would a Republican-controlled Congress end the institution here.

A Complicated Past

Is the U.S. Ready for a National Park Site Devoted to Reconstruction?

See more ›Yet the local anti-slavery community had long before set up escape routes and depots between Washington and Philadelphia, New York, and other points north. Only by chance did I learn that my ancestors were part of it. A single sentence left a trace in an old scholarly article: “Elizabeth Savoy, wife of Edward Savoy, a successful caterer, worked with the underground railway and helped slaves make their way northward to Canada and freedom.” One sentence in an article with no noted source. Yet 25 words revealed more about the kind of woman my great-great-grandmother was than “washerwoman” on a census ever could. Her husband made a “successful” living at a time when many respectable jobs were closed to free men of color.

A will and estate inventory. Census records. Death certificates. A chance note in a journal article. Land records from Silver Spring, Maryland, “lost” long ago. This Savoy line ends with me.

I stand again at the bank of the Potomac River, under an evening sun. Muddy waters course by, following a week of rain. As unmoored as driftwood in this swift current, I never felt at home in my father’s home.

Yet I, like my father, am a child of this river, of these tidewater and Piedmont lands, of a capital sited on the fall line. Those of my blood planted and harvested tobacco that drove the commerce of Chesapeake colonies. Ancestors might have helped build this capital city — or lain foundations for a monument to the man who brought the seat of government south.

Odysseus said, I belong in the place of my departure and I belong in the place that is my destination. To reach from California, the place of my birth, to this place of deeper origins, where roots began to twine, is a belated coming home.

The past and its landscapes lie close. They linger in eroded, scattered pieces, both becoming and passing into what I am, what I think we are. Perhaps the shadows of unnumbered years have touched me in choices made, in backward yearnings, in fears as well as dreams. Perhaps they form the natural and unnatural histories of my soul.

At the bank of the Potomac River I watch ripples rise, sun-jeweled for an instant, then disappear into the current. I will continue the search.

About the author

-

Lauret Savoy Professor of environmental studies and geology at Mount Holyoke College and NPCA Trustee

Lauret Savoy Professor of environmental studies and geology at Mount Holyoke College and NPCA TrusteeA professor of environmental studies and geology at Mount Holyoke College, Lauret Savoy explores the complex layering of natural and cultural histories, intersections of cultural identity and environmental awareness, and images and ideas about the American Earth. She writes about the stories we tell of the land’s origin and history, and the stories we tell of ourselves in the land.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Mid-Atlantic

-

Issues