One woman's journey to uncover her history and other missing stories of the American landscape

Seven years old on a sun-bright June day, she stands by the curio shop’s postcard rack. In their move across the country, her family has visited many national parks — Sequoia, Kings Canyon, Zion, Bryce, Grand Canyon — and at every stop, she runs first to the postcard rack.

Ten cents a card. She takes selected treasures to the cashier: Point Imperial at sunrise; goldening aspen groves; layered, dusk-lit canyon walls; brick-red river against brick-red rock. Each an image of light, texture, home.

Read the Book

The woman behind the counter tilts her head but greets a man approaching the register. She will help him. Marlboros. Then another customer. Postcards and questions about road conditions and nearby motor courts.

The girl stands quietly, her head at counter level. These people act as if she isn’t there. Through the display glass she examines polished stones and beaded place mats under sunlit dust. The room smells stale.

Only after all others have gone does the woman behind the counter extend her hand. Six cards, 60 cents. When the girl reaches up with three quarters the woman avoids the small hand to take the coins. Cash register clinks shut. The woman turns away.

The girl starts to ask but stops as the woman faces her. At 7, she doesn’t yet know contempt and runs far into the pinewoods behind the store. That night, with all her cards covering the motel bed, she wonders if each bright place is enough.

What can I say about this child and about a memory that remains sharp-edged after decades?

Then as now, I am the daughter of a woman with deep brown skin and dark eyes who married a fair-skinned man with blue-gray eyes. Yet as a little girl, I never knew race. Skin and eye color, hair color and texture, body height and shape varied greatly among relatives. Like the land, we appeared in many forms. That some differences held significance was beyond me. Instead I devised a theory that golden sunlight made me and deep blue sky flowed in my veins. Colored could only mean these things.

Yet, as I grew, I learned other things, such as lessons in fifth-grade social studies:

Our textbook describes Africans, who thrived as slaves and by nature want to serve. I ask my teacher, Mrs. Devlin, if I might become a slave.

We read in class that Indians are savages who had to give up the land and their wasteful way of life for the sake of civilization. The book calls this part of Manifest Destiny. Confused again, I ask what made the “five civilized nations” civilized?

Imagine searching for self-meaning in such lessons. Am I civilized? Will I be a slave? The history taught in school wasn’t the history that made me, but I didn’t know this. Any language to voice who I was, any knowledge of how land and time touched my family, remained elusive.

Once we moved from California to Washington, D.C., in the late 1960s, I came to learn how “race” cut our lives. Black, Negro, nigger! came loud and hard after the 1968 riots. Words full of spit showed that I could be hated for being “colored.” By the age of 8, I wondered if I should hate in return.

What I couldn’t grasp then was that twining roots from different continents could never be crammed into a single box. I descend from Africans who came in chains and Africans who may never have known bondage. From European colonists who tried to make a start in a world new to them, as well as from Native peoples who were displaced by those colonists from homelands that had defined their essential being.

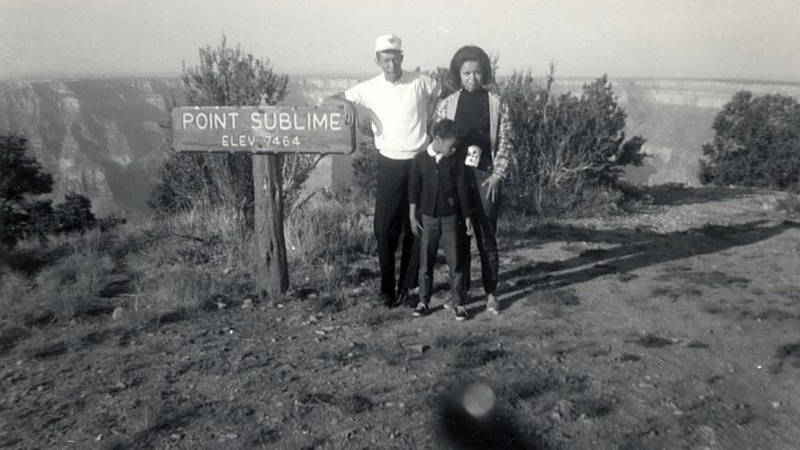

The View from Point Sublime

How a child’s first visit to the Grand Canyon seeded a life-long path.

See more ›As the 19th century ended, known family members had dwelled in rural Virginia, Maryland, Alabama, perhaps Oklahoma, and Montana ranchland along the Yellowstone River. They came to live in cities like Washington, D.C., and Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. But how they experienced the world or defined themselves in it remained unknown. Forced removal, slavery and Jim Crow were at odds with propertied privilege. My forebears likely navigated a tangled mélange of land relations: inclusion and exclusion, ownership and tenancy, investment and dispossession. Some ancestors knew land intimately as home, others worked it as enslaved laborers for its yield. What senses of belonging were possible when one couldn’t guarantee a life in place? Or when “freed” in a land where racialized thinking bounded such freedom?

But so much of my family’s past was obscured by silence — the silence of voices lost to history and of my own parents’ reluctance to tell me about generations that preceded us. These unvoiced lives cut a sharp-felt absence. Neither school lessons nor images surging around me could offer salve or substitute. My greatest fear as a young girl was that I wasn’t meant to exist.

Yet one idea stood firm: Whether a river named Colorado or a canyon called Grand, the American land did not hate. The Western parks and monuments that I visited with my parents were far more than destinations for recreation or Kodak moments. To the child I was, they became refuges from a world that made little sense.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

An immense land lies about us. Nations migrate within us. What I can know of my ancestors’ lives or of this continent can’t be retrieved like old worn postcards stored in my desk drawer. My task is to uncover missing stories of the American landscape, of its past to present — and to give voice to those who, even in their apparent absence, still mark a very real presence. In my journeys to our national parklands and other places, I seek not only fragments of my own origins but traces of a still-unfolding history that touches us all.

About the author

-

Lauret Savoy Professor of environmental studies and geology at Mount Holyoke College and NPCA Trustee

Lauret Savoy Professor of environmental studies and geology at Mount Holyoke College and NPCA TrusteeA professor of environmental studies and geology at Mount Holyoke College, Lauret Savoy explores the complex layering of natural and cultural histories, intersections of cultural identity and environmental awareness, and images and ideas about the American Earth. She writes about the stories we tell of the land’s origin and history, and the stories we tell of ourselves in the land.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Southwest

-

Issues