Mid-Atlantic Climate Impacts

Coastal challenges

Sea Level Rise

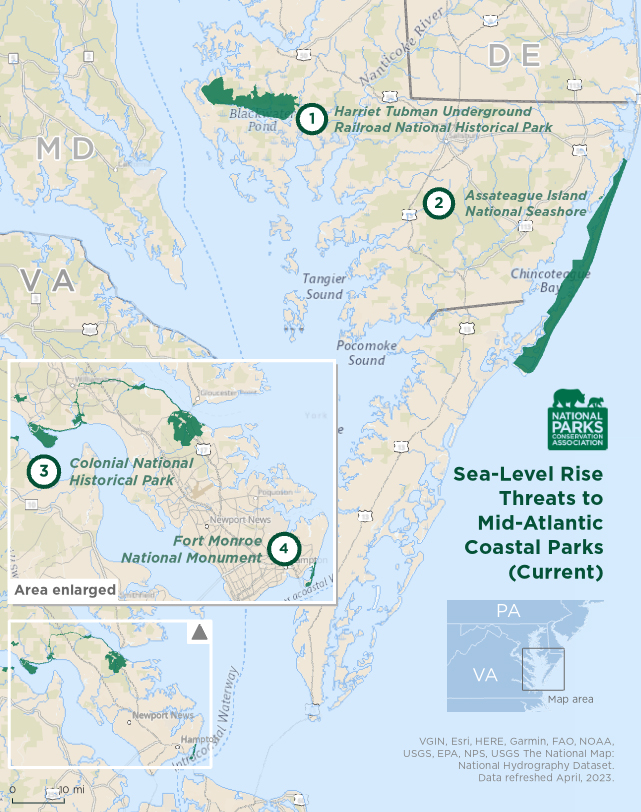

Sea level rise is one of the greatest threats to coastal parks the Mid-Atlantic region. The coastal part of the region not only has the second-highest sea level rise in the U.S., but its annual rate of 0.22 inches per year exceeds the global trend of about 0.13 inches per year. The coast of Delaware has seen sea level rise at a rate of more than one foot per century. Communities and parks on the low-lying eastern shore of the Chesapeake Bay are particularly vulnerable to flooding.

The acceleration of ice sheet and glacier melting serves as a crucial factor contributing to the rise in sea levels, while land subsidence exacerbates the issue by causing the already low-lying land in the Mid-Atlantic to sink further. Addressing and mitigating the impacts of sea level rise is of paramount importance to safeguard the communities and natural assets in the Mid-Atlantic region.

Coastal communities in the Mid-Atlantic region are facing an imminent threat due to sea level rise. A particularly alarming example can be found in coastal Virginia. Since 1930, this area has experienced a staggering rise of more than 14 inches, further accelerating the sinking of communities like Hampton Roads, where Fort Monroe National Monument is located. In 2022, the annual sea level report card from the Virginia Institute of Marine Science (VIMS), found that Norfolk, Virginia had the highest rise rate of sea level rise along the East Coast.

In major urban centers like Washington D.C., there are dense waterfront communities facing increased vulnerabilities to sea level rise. Approximately 1,350 acres of land in D.C. lie less than 6 feet above the highest tide line observed each day. This concerning situation is further compounded by Climate Central’s report that projected a more optimistic climate scenario predicting D.C. to flood more than 6 feet above the local high tide line by 2030. Under higher emissions and more rapid rise of global temperatures, the city can flood by 10 feet. With such vast areas lying low, the potential for rapid inundation is worrisome if sea level rise continues unchecked.

Even iconic national parks like the National Mall Memorial Parks are not immune from sea level rise, as they are situated in low-lying areas near the water in D.C. To address this urgent issue, the National Park Service has taken a step forward with the rehabilitation of a 6,800 feet seawall along West Potomac Park and parts of the Tidal Basin, thanks to funding from the Great American Outdoors Act. However, with sea levels rising at a dramatic pace and increasing flooding from rain events, further measures are imperative to effectively respond to this pressing challenge. Proactive measures and strategic planning are vital to safeguard the communities, cultural heritage, and natural resources of Washington D.C. from the intensifying impacts of rising sea levels.

Deterioration of Tidal Wetlands

Tidal wetlands are an important part of Mid-Atlantic coastal areas. The Atlantic Coast has the second largest amount (12 million acres) of wetlands after the Gulf Coast. In Maryland alone, there are 3,100 miles of tidal shoreline, encompassing both Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. These wetlands provide important ecosystem and community benefits. They control erosion, improve water quality, and help sequester carbon. Wetlands are a vital habitat for wildlife and create recreation opportunities. However, tidal wetlands often lie less than one meter above sea level, so even a small increase in sea level can easily destroy coastal tidal wetlands. From 1983 and 2006, sea level rise inundated 3,000 acres of forest and agricultural land and 5,000 acres of marsh in Maryland’s Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge where Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad National Historic Park is located.

In response to rising sea levels, in places where tidal wetlands have room to move, they can migrate towards higher ground allowing them to adapt to changing and unfavorable conditions. However, this transformation along coastlines can disturb the existing upland ecosystem and infiltrate freshwater wetlands. In the Mid-Atlantic, the Chesapeake Bay estuary is at the risk of a “catastrophic, landscape-scale wetland loss” on the same level of threat as wetlands of the Gulf Coast. In the Washington, D.C. area, on the Potomac River, Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve is the largest remaining freshwater tidal wetland where more than 250 bird species have been spotted. Due to sea level rise, the long-term survival of the marsh is at risk from flooding and erosion. Around 50 years ago, Dyke Marsh Wildlife Preserve was about 650 acres large, however dredging has shrunk the marsh’s size to 485 acres today.

Shoreline Erosion

National Mall and the Tidal Basin

NPSClimate change is exacerbating the rate at which coastal areas are affected by erosion. Sea level rise, powerful storms, flooding, and strong waves, all with increasing impacts due to climate change, are speeding up the process by which sand, soil, and rocks are washed away into the ocean from shorelines, beaches, cliffs, and wetlands. A 2011 study by the U.S. Geological Survey found that 65% of shorelines in the New England and Mid-Atlantic regions are eroding. The study found the greatest concentrated area of erosion at 83% is occurring in the Delmarva South/ Southern Virginia region. The south end of Hog Island, Virginia is eroding the fastest at 61 feet per year.

“Nuisance” Flooding

With rising sea levels, “nuisance” flooding, or “sunny day” flooding, is becoming more prevalent along riverfronts due to high tides, even in the absence of storms or heavy precipitation. The Potomac and Anacostia tidal rivers have experienced an 11-inch rise in just 90 years, leading to over a 300 percent increase in nuisance flooding. Locations like Washington, D.C., have witnessed record-breaking incidents of nuisance flooding between May 2018 and April 2019. In Annapolis, Maryland, tidal flooding, which was infrequent in the 1950s, now occurs 40 or more times annually. NOAA projects that Annapolis may experience 75 nuisance flooding events each year by 2050. These escalating flood events highlight the urgent need for adaptive measures to safeguard communities, infrastructure, and assets from the impacts of sea level rise.

What does this mean for national parks?

Several national parks in the Mid-Atlantic region are at low-lying elevations, at or near sea level. The National Mall and Memorial Parks in D.C. are threatened by flooding from the rising of the Potomac River. Of all the coastal national parks in northeast region, Colonial National Historical Park and Fort Monroe National Monument have the highest projected sea level rise in 2050 and 2100, according to NPS. These two parks, located in Virginia, are extremely vulnerable to flood risks.

Jamestown Island at Colonial National Historical Park is less than 3 feet above the current waterline and increasingly exposed to climate risks such as sea level rise, storm surges, and erosion. These environmental challenges pose a significant threat to America’s historical legacy as the island holds immense cultural significance as the site of the first permanent English settlement in North America. Without adequate measures to mitigate climate impacts, the erosion and inundation of Jamestown Island could result in the loss of invaluable historical artifacts, structures, and the physical remnants of America’s colonial past.

The 37-mile-long Assateague Island National Seashore along the Atlantic Coast has been moving westward more quickly due to sea level rise. While migration is a natural process of barrier islands especially during major storm events, sea level rise has been accelerating the island’s move.

Make a tax-deductible gift today to provide a brighter future for our national parks and the millions of Americans who enjoy them.

Donate Now