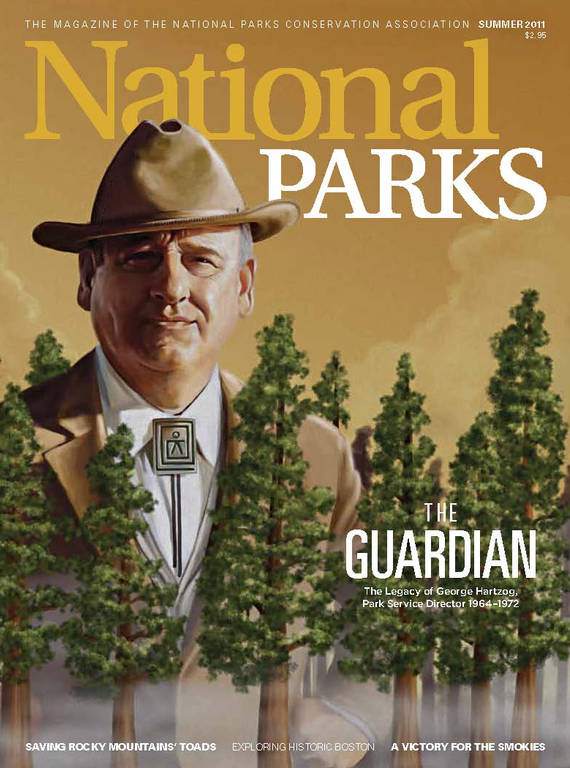

Summer 2011

At the Water’s Edge

Deep in the heart of Rocky Mountain National Park, researchers are working to save the boreal toad from extinction.

With nine miles down and one to go, Erin Kenison and Leah Swartz of the United States Geological Survey (USGS) push deep into the heart of Rocky Mountain National Park. Weighed down by the bulk of their overstuffed backpacks with dark brown fishing waders fastened awkwardly to the sides, the researchers hike through the thinning tree line to one of the most remote locations in this protected area, Lost Lake. At an elevation of 10,711 feet, Lost Lake is a destination reached by only a handful of people each year, but USGS researchers have been making this trek for more than 20 years. Dedicated to understanding the factors associated with amphibian decline, the agency’s scientists come to this site again and again to monitor one of the last remaining populations of boreal toads in Rocky Mountain National Park. A once-familiar sight in this remote glacial lake, boreal toads could be found by the hundreds. This year Kenison and Swartz didn’t find a single one.

As a group, amphibians are declining more dramatically than any other class of vertebrate, and the future of some species is in serious doubt. Having already vanished throughout much of the southern Rocky Mountains, the boreal toad is one species with a questionable future. Beginning in the 1970s, the species began disappearing throughout much of Colorado’s high country. Rocky Mountain National Park is now one of only a small number of places where this high-elevation amphibian is still hanging on. But this wasn’t always the case.

In the early ’90s the USGS, led by Dr. Steve Corn and later Dr. Erin Muths, began monitoring boreal toad populations within Rocky Mountain National Park. When they first began, toad populations in the park appeared to be thriving. Sites such as the North Fork drainage, which encompasses two important breeding sites (Lost Lake and Kettle Tarn), provided habitat for more than 700 toads. But populations such as those in the North Fork drainage experienced dramatic declines between 1996 and 1999. “The year I started work, we captured and released more than 80 toads at Kettle Tarn,” says Muths. “Over the next two to five years, we found fewer and fewer toads. Now we get excited if we see one or two.”

With the toad’s populations nearly depleted, researchers at the USGS continue to dedicate countless hours to understanding the driving forces behind these declines. Habitat loss, invasive species, and disease epidemics are still the most significant causes of global amphibian decline. Today, toads persist in only three of the 19 breeding sites known two decades ago. Only one site has had consistent breeding over the last decade—at a lake deep within the park’s interior, which the Park Service would rather not identify to the public, given the species’ fragile existence. And that’s where Kenison and Swartz are focusing much of their research, to find out just what makes this population so special.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Here, Kenison delicately rubs a cotton swab across a speckled belly, collecting a specimen from one of the remaining toads. She’s looking for the presence of the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis or Bd. This type of fungus is found worldwide, but this particular strain is specific to amphibians. By producing waterborne spores that can land on an amphibian’s skin, the fungus is able to burrow in and produce more spores. Causing a thickening of the skin, Bd interferes with water uptake and the toad’s ability to regulate electrolytes, eventually leading to the death of the animal.

Bd is associated with declines and extinction in the Western United States, such as the mountain yellow-legged frog (Rana muscosa) in the Sierra Nevada Mountains of Southern California. The disease has a global presence and has had particularly devastating impacts on amphibian communities in Australia, Costa Rica, and Panama. In an effort to keep the boreal toad from going the way of so many others, the USGS has been working to understand all aspects of the fungus and its impact on the toads.

“Dealing with Bd is a real challenge,” says Muths. “At this point we have no cure, and no way to thoroughly mitigate for its impacts.” Treating Bd in the field is still in the experimental stages, and although it may be a viable alternative in the future, the USGS continues to look at other approaches to ameliorate the impacts of Bd and stabilize toad populations in the park. Current research focuses on efforts to understand how populations respond after being nearly wiped out and determine if they have the ability to bounce back. Data collected from park populations and other populations of boreal toads allow researchers to examine demographic characteristics such as survival and recruitment (the addition of new breeding adults into a population), and to look at patterns in movements and breeding events. This information could prove vital in understanding how toad populations cope with disease. Only three populations out of the 19 that existed 20 years ago still persist in Rocky Mountain National Park. Understanding why these populations survive when others have gone extinct may help biologists protect the species.

Even with the species on the verge of extirpation, there are still signs of hope for the boreal toads of Rocky Mountain National Park. With a few breeding populations holding on and new toads and tadpoles being observed in areas where they were once thought extinct, researchers remain optimistic. After 20 years of devastating losses, small numbers of toads can still be seen gathering along the shorelines of a few high mountain lakes. In fact, in the fall of 2010, a few months after Kenison and Swartz reported finding no toads at Lost Lake, researchers at USGS found tadpoles and recently metamorphosed toads at the site—which means there may still be a glimmer of hope just beneath the water’s surface.

About the author

-

David Herasimtschuk Contributor

David Herasimtschuk ContributorDavid Herasimtschuk is a Colorado-based photographer and writer who focuses on the conservation of freshwater species and ecosystems.