Spring 2025

Whistleblowers

A warming climate is shrinking the habitat of North Cascades’ hoary marmots while expanding the range of some predators. Can the rodents adapt in time to survive?

It’s a welcome wildlife encounter for the high-country backpacker in northern climes: the sight of a hoary marmot perched on a rock, paws aquiver, screaming to warn its colony of an intruder. This distinctive cry has earned marmots the affectionate nickname “whistle pigs.”

But now these chubby rodents are sounding the alarm on a more insidious threat — climate change. From 2007 to 2016, hoary marmot populations in Washington state’s North Cascades National Park and nearby areas declined by 74%, a drop researchers attribute, in part, to a warming climate.

“They’re getting pushed higher and higher, to the tops of mountains,” said Logan Whiles, a wildlife biologist and lead author of a recent paper on marmots in the park as well as in Lake Chelan and Ross Lake national recreation areas. “The land area is disappearing out from under their feet.”

Named for the frost-colored fur on their upper bodies, hoary marmots play an important role in the high Cascades, at the southern edge of the species’ range. The largest members of the ground squirrel family in North America — an adult can weigh 15 pounds — hoary marmots are natural engineers that dig extensive burrows and trim meadow vegetation like fastidious landscapers. Marmots live in splendor, on talus slopes interwoven with wildflower-dotted patches of tundra.

“They’re looking at this postcard image we see of the Cascades,” said Jason Ransom, the park’s wildlife program supervisor and a co-author of the recent paper. “It’s not a bad place to be, but it’s also a really harsh environment.”

The population of hoary marmots in North Cascades National Park as well as Lake Chelan and Ross Lake national recreation areas declined 74% between 2007 and 2016.

COURTESY OF JASON I. RANSOMUnfortunately, that environment is getting harsher. As the climate warms, less consistent snowfall means less insulation covering marmots’ burrows.

“A good, deep, fluffy snowpack is just the perfect winter blanket for marmots while they’re spending eight months of the year hibernating,” Whiles said. “But if the snow sucks and a nasty winter night rolls through, then their physiology is going to take a hit.”

Earlier research in the park found that poor snowpack combined with extreme cold and unusually dry air heightened marmot mortality and hurt reproduction. Another threat might be looming, too. Marmots are high-calorie prey for alpine carnivores, including Canada lynx and wolverines. Could climate change also make marmots more vulnerable to lower-elevation predators such as black bears and bobcats? Whiles took on that question for his master’s thesis at Washington State University.

Whiles, Ransom and a small crew of researchers spent the summers of 2018 and 2019 in the park collecting data. They set camera traps to detect predators near 32 marmot colonies, gathered carnivore feces to determine which species are eating the most marmots, and observed marmot behavior.

The land area is disappearing out from under their feet.

From a base camp in the remote community of Stehekin, Whiles and an assistant would lug backpacks 15 miles into the mountains to a marmot colony. The following morning they’d wake early, when marmots are most active, to see how much time individuals spent foraging versus scanning for predators and at what distance they fled an approaching human. Then the researchers would check trail cameras, collect scat and walk to the next colony.

Before this, the closest Whiles had come to marmots was spotting groundhogs around his childhood home in suburban Tennessee. So he felt lucky to spend days in the Cascades watching marmots frolic, play-fight and flatten themselves on the snow to cool down.

How the Climate Crisis Is Affecting National Parks

Climate change is the greatest threat the national parks have ever faced. Nearly everything we know and love about the parks — their plants and animals, rivers and lakes, glaciers,…

See more ›“They’re just really social and kind of goofy,” Whiles said. “They love to wrestle when they’re young. They get up on a boulder and play king of the hill to see who’s the biggest and baddest. Sometimes they get really frisky and try to wrestle their mom, and she’ll slap them back in their place because she’s still three times their size.”

The research had its lows, too. Whiles battled blisters, boot-bruised toenails and freak snowstorms. The hardest part, though, was the poop. Whiles and his team collected more than 500 scat samples from eight carnivore species. They hauled the excrement back to base camp and dried it in a shed.

Black bear scat was the worst. “Because they’re mostly vegetarian, it’s this really wet salad of huckleberries and grasses and stuff,” Whiles said. “That was really weighing us down.”

DNA analysis revealed that half the samples containing marmot remains were coyote scat. One-third were Pacific marten feces, the first known evidence of this species preying on marmots. Marmots were also found in the scat of gray wolves, cougars and black bears.

After poring over hundreds of thousands of photos from camera traps near marmot colonies, researchers detected 10 potential predators, including Cascade red foxes, Canada lynx and wolverines. Whiles predicted that lower-elevation predators — such as cougars, coyotes and gray wolves — would show up most often at sites with earlier snowmelt. He found this was only true for coyotes.

Though the researchers’ days were long and conditions could be grueling, the scenery was spectacular.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESMembers of the field crew examine scat samples.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESA photo of a black bear caught on one of the field crew’s camera traps.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESCougars were one of the animals found to prey on marmots through DNA analysis of collected scat.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESOther species caught on camera included Canada lynx (pictured), Cascade red fox and wolverine.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESThough the researchers’ days were long and conditions could be grueling, the scenery was spectacular.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESMembers of the field crew examine scat samples.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESA photo of a black bear caught on one of the field crew’s camera traps.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESCougars were one of the animals found to prey on marmots through DNA analysis of collected scat.

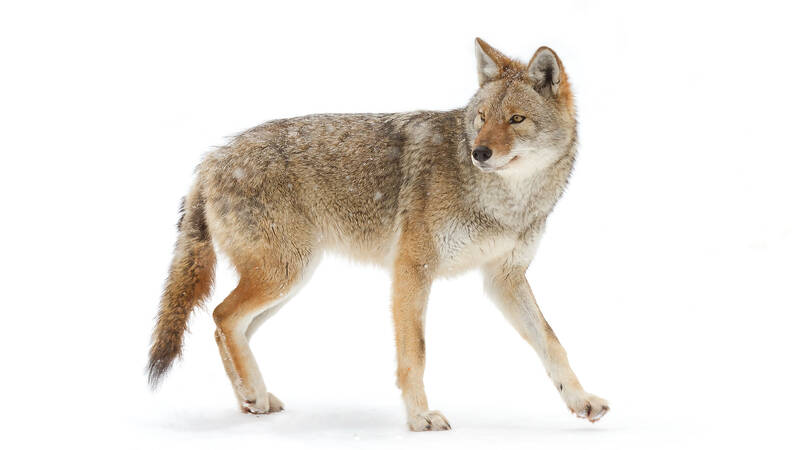

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILESOther species caught on camera included Canada lynx (pictured), Cascade red fox and wolverine.

COURTESY OF LOGAN WHILES“Coyotes are getting up real high into snowy places that I don’t think people used to associate with coyotes,” Whiles said. Snow acts as a barrier to coyotes, Whiles explained, because it requires energy to traverse. But if snow melts early or freezing rain creates a walkable crust, coyotes could spend more time hunting up high, where marmots live.

Curiously, Whiles and his team found that marmot colonies with more predators detected in nearby camera traps didn’t display increased vigilance. The marmots spent a little over half of their time scouting for danger, regardless of whether there were more predators around.

If snow melts early or freezing rain creates a walkable crust, coyotes could spend more time hunting up high, where marmots live.

JIM CUMMING/ADOBE STOCKIt’s unclear why marmots don’t devote more time on the lookout in colonies where predators are more abundant, but perhaps they are just managing their resources as best they can. Ransom said vigilance comes with a caloric cost.

“Time is energy and that’s life,” Ransom said. “So how much time do you not eat when you have to look for carnivores?”

With nowhere left to climb, North Cascades’ hoary marmots seem to be clinging to the crow’s nest of a sinking ship, encircled by hungry coyotes below. Still, Ransom and Whiles said there are reasons for hope. Earlier snowmelt, for example, may mean more food for marmots as grasses and wildflowers get a head start in their growing season. Population fluctuations are common, too, so it’s possible marmot numbers could recover. “Marmots go through boom-and-bust cycles,” Ransom said. “How far can you bust before you don’t boom again? We don’t know the answer to that.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›For now, Ransom is encouraged that he frequently sees marmots when hiking in the park, in all the high, beautiful places he’d expect them. “Nature has historically always found a way to persist,” he said.

Whiles pointed to one colony near Rainbow Lake where marmots were having more babies than any colony observed in the park since 2007. When he thinks of marmots facing new environmental pressures, that colony lifts his spirits.

“Climate change as a whole is definitely bad news for marmots,” Whiles said. “But I don’t know. They are smart little mammals, and they already have to put up with a difficult life in this high-altitude environment. I hope they have it in their toolbox to adapt and make it through.”