Fall 2015

The National Park Next Door

Nearly six million people in the D.C. region live within a short drive of Oxon Cove. Why aren’t more of them visiting it?

In front of a yellow sign warning of sewage overflows, Tony Carter dangled his rod into the flat waters of Oxon Cove. Around him was the flotsam of urban life—potato chip bags, a few soda cans, and other assorted junk. His son, Ronald, helped bait the hook. They waited, father and son, their water view giving way to highways and belching smokestacks. On a beautiful spring day, they were the only visitors fishing in the park.

Carter soon caught a catfish, and his son’s face was alive with pride. The two have snagged bluegill, bass, and crappie here, too, but Carter always throws them back. He doesn’t have to release them all, but he worries about toxins in the water. Those concerns, however, would never stop him from coming, he says. In a paved-over watershed, where else can he show his child foxes, snakes, and turkeys?

“I love it,” he said, “because it gives me a chance to introduce my son to nature.”

Oxon Cove and the adjacent Oxon Hill Farm make for a paradox park—near so many, but known to so few. The 500-acre property, which is part of the National Park System, is just off the busy Capital Beltway and only a few miles from the U.S. Capitol Building and the National Mall. For hikers and bikers, it provides trails shaded by beech, cherry, and oak trees. Birders routinely spot eagles and osprey and even orioles here. Children love to meet the tolerant pony mule and the goats and chickens at the 70-acre farm. History buffs enjoy touring the DeButts family farmhouse, which offered its residents an unforgettable view of the bloody battle of Bladensburg during the War of 1812.

But while nearly six million residents live within a short drive of the park, only 30,000 visitors find it every year. Most don’t discover it themselves but are brought there on school field trips. And as more people have moved into the fast-growing area around the park, Oxon Cove has become even harder to find and, its advocates say, even more endangered. They worry that with construction booming at nearby National Harbor—a mega-project that will eventually house a billion-dollar casino, an outlet mall, condominiums, hotels, and restaurants—the park will be forgotten, or worse, will fall victim to the development encircling it. Already, construction is encroaching and Oxon Cove is suffering from neglect. Bike trails are rutted and in disrepair. Trash bobs in the waterway. Construction cranes loom over the walking paths. On one side of the park is the outlet mall; on the other, one of the nation’s largest sewage treatment plants.

“Right now, I’d say that development is the known threat. This is the only pocket cove of green space on the southern end of the Potomac River in D.C., and it’s really important to preserve it,” said Ed Stierli, NPCA’s Chesapeake field representative. “They always say they’re in the forever business at the National Park Service, and we want to make sure they mean it.”

The visitors who discover the farm and walk down to the cove will be rewarded with a panorama of Northern Virginia’s shiny office buildings, the area’s many military bases, and an urban waterway that is by turns beautiful and utterly distressing. There are diving cormorants and gliding ducks, discarded cans, and an occasional foul smell.

Two hundred years ago, the area was wetlands and farmland dotted with the early buildings of the nation’s fledgling capital. The DeButts family owned the property, and the white farmhouse where they resided remains open for tours. Those who visit can look across the Potomac and imagine the view that Mary DeButts witnessed from her farmhouse during the War of 1812. Washington was burning, and the British would soon make their way to Baltimore, where they would underestimate the might of the port city and eventually lose the war.

“I cannot express to you the distress it has occasioned at the Battle of Bladensburg. We heard every fire. Our house was shook repeatedly by the firing upon forts and bridges, and illuminated by the fires in our Capital,” Mary DeButts wrote to her sister, Millicent, in 1815.

In those days, Oxon Cove was a plantation where slaves worked the vast grounds. It remained a working farm until the DeButts family sold the property to the U.S. government so it could establish a therapeutic farm there. The farm, called Godding Croft, was part of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital. Doctors hoped that being outside and among the animals would be therapeutic for the mentally ill patients, many of them members of the military.

In 1967, the Park Service acquired the property with a mandate to protect it from development. Today, activities at the park include tours of the historic plantation home, Mount Welby; bird-watching walks; and opportunities to milk the farm’s cow.

National Capital Parks-East

Includes a rich diversity of sites in Washington, D.C. including the 1,200-acre Anacostia Park along the banks of the Anacostia River, Kenilworth Aquatic Gardens, and the Fort Circle Parks that…

See more ›But despite its central location, its miles of bike routes, its water views, and its moss-covered trails, Oxon Cove has attracted little investment and attention compared with other nearby national parks and landmarks, and it shows. Jim Hudnall, of the Oxon Hill Bicycle and Trail Club, once commuted along the park’s bike trail on his way to work at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory just north of the cove. Today, he said, some commuters he used to see are skipping the park and taking a different set of bike lanes to connect to downtown Washington. They are a little leery of veering into Southeast Washington, D.C., which has long been struggling with a high crime rate despite a lot of investment and the new Nationals ballpark. And navigating the trails in Oxon Cove can be challenging.

“There are some rough spots, and there are some places where the asphalt has crumbled,” Hudnall said. “Some of the pavement is broken up.”

Oxon Cove should be having a moment. Nationwide, urban areas are embracing the wildlife around them. Federal agencies are focused on acquiring urban parkland, making better uses of the spaces that the public already owns, or providing funds to clean up dump sites and old industrial lands to create suitable park space. In 2013, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service named ten urban wildlife refuges as part of an Obama Administration initiative that aims to connect more Americans to nature. The Park Service also has a major urban agenda, which includes identifying nine “model cities” that have a system of parks residents can easily navigate. Washington, D.C., is one such model city.

City residents are taking to urban parks and waterways despite the pollution, and their presence in places that were once written off is developing a constituency to fight for clean water. In Chicago, paddlers amble along the city’s namesake river and hike through its wilderness. In Pittsburgh, mountain bikers traverse trails that were once dumps for steel waste. Boston hosts a river swim every year in its once-fetid harbor. Even across from Oxon Cove, the Anacostia River’s traffic has increased dramatically, and so has the clamor for reducing pollution in the area. Washington, D.C., passed a plastic-bag ban, and nearby Prince George’s County has passed a ban on polystyrene foam food containers and packing material.

But even with a motivated public, the Oxon Cove area seems forgotten.

“It gets left out a lot,” said Julie Lawson, executive director of Trash Free Maryland. “It just doesn’t get the investment it needs.”

A clean-up event along the shore of the Potomac River in April

© GASTON LACOMBEThe park schedules regular cleanups, but staff say these events generally bring only a handful of volunteers. In contrast, a cleanup day at other local parks can bring in hundreds, if not thousands, of volunteers. Funding is clearly also part of the problem: National Capital Parks-East, the group of national park sites that includes Oxon Cove, has seen its budget reduced repeatedly by Congress in the last five years.

Those who love the park see potential beyond what it is today. Don Briggs, superintendent for the Park Service’s nearby Potomac Heritage National Scenic Trail, envisions Oxon Cove Park as a connector between the bike trails along the Anacostia and Potomac Rivers, which could take cyclists from Washington all the way out to Harper’s Ferry in West Virginia. Oxon Cove, he said, could serve as a trailhead for multiple routes; it has parking, bathrooms, and activities for kids.

The Park Service and the next-door town of Forest Heights would like to open and extend the western part of the park next to the D.C. impound lot to provide visitors with more opportunities to enjoy the Potomac River. The Park Service requested public comment on the plan this past spring, but with tight funds, park advocates worry the agency will never implement the proposal.

Meanwhile, just finding Oxon Cove can be tricky. Construction has rerouted traffic in such a way that many motorists miss the park’s wooden sign, noted Oxon Cove Supervisory Park Ranger Adam Gresek. With the entrance poorly marked, visitors frequently end up making U-turns on the two main roads heading into the park. Mapquest, Google Maps, and other navigational tools aren’t helpful, either.

“We’re trying to figure out what authority to talk to so we can actually get an address,” Gresek said.

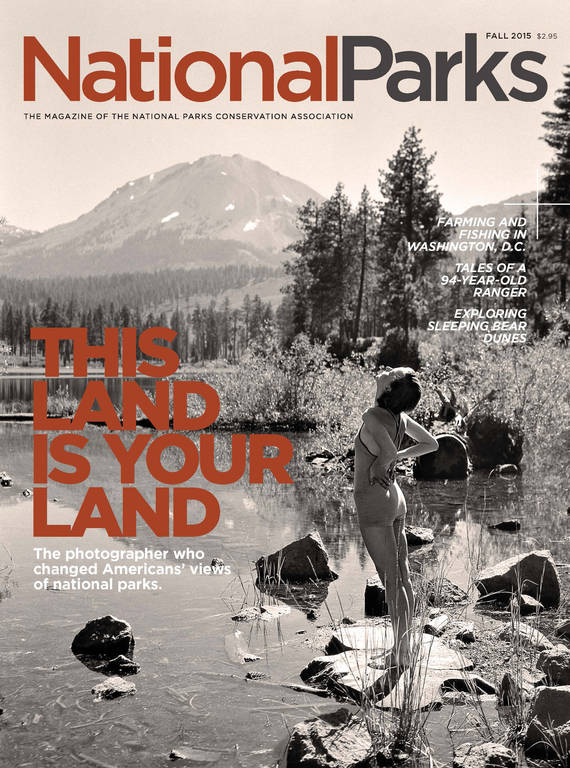

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›In the longer term, the park’s very existence may be threatened as developers covet the land and cash-strapped governments have a hard time saying no. Though the Park Service owns the property, which is split between Washington, D.C., and Maryland, that alone doesn’t guarantee it will remain a park. Indeed, over the past three decades, both the federal government and local developers have hatched plans to turn part of the park into a women’s prison, a golf course, and housing.

None of those plans came to pass, but a dramatic overhaul isn’t unthinkable given how quickly change has come to this once neglected stretch of southern Washington, D.C. Last year, Forest Heights “annexed” the park, a maneuver that raised eyebrows among conservationists. Forest Heights Mayor Jacqueline Goodall said the town did so to protect the park and that the annexation will allow it to make better future planning decisions about roads, trails, bike paths, and waterways. The town has neither the desire nor the intention to develop the park, she said, and she’s aware that the town can’t substantially modify the park without federal approval.

About the Photographer

With major bike trail improvements, the park would likely see more visitors like Bo Bodniewicz, an environmental engineer from Alexandria, Virginia, who bikes through the park every day on his way to work in the District. On weekends, he brings his toddler, Diana, who loves the cows and sheep.

Bodniewicz said he dreamed of living in a city where he could bike to work, but never thought he’d be whizzing by a working farm every morning. Like the other park supporters, he worries about the park’s future—especially because in his line of work, he has seen many environmental treasures lost.

“This is a national park,” Bodniewicz said, “but it’s not out of the realm of possibility for deals to be made.”

Tony Carter and his son Ronald frequently fish in Oxon Cove, where they’ve caught bluegill, bass, crappie, and catfish.

© GASTON LACOMBENeil Koch hopes that doesn’t come to pass. The Park Service ranger, who usually works nearby at the National Mall, was leading a group through the cove to help the understaffed park on National Bird Migration Day. As they made their way along the hiker-biker trail to the cove, several cormorants and an oriole sailed overhead. For many in the group, it was their first sight of the bird outside of Camden Yards ballpark, where it is actually a man dressed in an orange and black costume.

Koch marveled at both the oriole and the Carters, the pair who were fishing that day. Though the bird-watching program and children’s activities had been well advertised, very few visitors beyond this small cluster had found their way to the park. That, Koch said, would never happen at the National Mall.

“This is right on the doorstep of Washington, D.C.,” Koch said. “Gosh almighty, father-son fishing. Why aren’t we seeing more of that?”

About the author

-

Rona Kobell Author

Rona Kobell AuthorRona Kobell, a frequent National Parks magazine contributor, is the co-founder of the Environmental Justice Journalism Initiative. She is also a professor of journalism and has written about the Chesapeake Bay for 20 years. Reach her at rona@ejji.org.