Summer 2024

The Dog Trainers of Cat Island

During World War II, the U.S. Army attempted to train dogs to hunt Japanese soldiers. The secret experiment on an island off the Gulf Coast did not go well.

In the summer of 1942, six months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. War Department received a curious letter from William A. Prestre, a Swiss immigrant living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. A former Swiss army officer and hunting guide, Prestre claimed he possessed the skills to train an elite new fighting force for the U.S. Army to deploy in the Pacific theater: a lethal pack of attack dogs.

Intrigued, the Army secured for Prestre dozens of dogs donated by civilians and identified a secret location for Prestre’s experimental program: the inaptly named Cat Island off the coast of Gulfport, Mississippi, now part of the Gulf Islands National Seashore.

An American Journey

Was the story of Minidoka National Historic Site his story, too?

See more ›“His idea was that he could train the dogs to attack Japanese people specifically, and that the dogs would be able to smell them,” said park guide Victor Pillow of an experiment that was racist and misguided from the start.

For his project, Prestre needed people the dogs could learn to attack. His Army handler mused over the possibilities in a telegram to his superior. “The first choice is prisoners and the second choice is aliens,” he wrote, “preferably without families in this country.” The sensitivity of the program prompted this additional warning: “You better tear this letter up and eat it.”

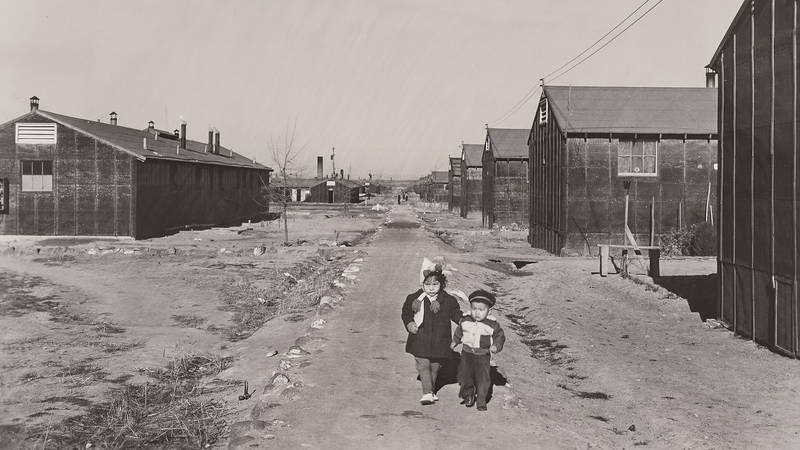

Eventually, the Army decided that Prestre’s targets would be 25 soldiers from the 100th Infantry Battalion (Separate), a segregated unit of Japanese American draftees from the Hawaii National Guard. During the rampant paranoia that followed Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government rounded up many thousands of people with Japanese ancestry and incarcerated them in remote camps. The War Department didn’t trust the Japanese American soldiers enough to leave them in Hawaii, so the battalion was shipped to Camp McCoy, Wisconsin, where they could train under close observation.

Raymond Nosaka, a 26-year-old private born to Japanese immigrants in Honolulu, was one of the 25 men from the 100th chosen for Prestre’s dog training program. The men weren’t told anything about the mission or where they were going because the Army wanted the program kept under wraps.

“The utmost secrecy will be maintained,” one military letter read at the time. “Such use of Japanese Americans, even though American soldiers, might cause adverse public sentiment, could furnish the basis of a serious charge by the enemy, and might result in reciprocal action against American prisoners in the hands of the Japanese.”

In early November 1942, Nosaka and the other soldiers were loaded onto a plane that flew them south. Noticing the scenery getting greener as they flew, some soldiers wondered if they were going home to Hawaii. Instead, they landed in Gulfport where, under cover of darkness, they boarded two Coast Guard boats and motored out to Ship Island. Every day the men would boat 6 miles from there to Cat Island.

Return to Manzanar

As the number of Japanese-American incarceration camp survivors dwindles, a new generation strives to keep the story alive.

See more ›Cat Island got its name from early seafarers who thought the local raccoons resembled European wildcats. The island is swampy, bug-infested and T-shaped and was once the haunt of pirates, mercenaries and Prohibition-era bootleggers. Densely vegetated with moss-hung live oak, slash pine and palmettos, it was chosen by the Army to approximate the South Pacific jungle.

In the beginning, the men from the 100th were ordered to hide in the swamp, sometimes waiting in trees where they could avoid the alligators, if not the mosquitoes. When the dogs found them, the soldiers fired a shot from a pistol and then fell over, “dead,” letting the dogs eat horse meat that they held near their necks. The dogs — German shepherds, boxers, wolfhounds and other breeds — would lick the men’s faces.

Prestre worried the dogs were becoming too friendly with the Japanese American soldiers, so he tied the dogs to a fence and ordered the men to whip them until they bled. Nosaka grew up with dogs and hated hitting the animals, but he had to follow his orders. The chained dogs snarled and lunged at him. When they were sufficiently angry, a sergeant would release them and shout: “Kill him!” The dogs would bite Nosaka, dressed in protective hockey gear, on his legs, feet and arms. The animals’ jaws felt like the pinch of pliers.

Today, when you look back, you say, ‘How did that happen, and why?’

“They said to ‘train the dogs,’ but we called it ‘dog bait.’ We were the bait,” Nosaka said in a 2005 oral history interview. “That’s one of the things that the Japanese Americans had to do. Today, when you look back, you say, ‘How did that happen, and why?’”

Grim as it sounds, the soldiers’ experience wasn’t all bad, Nosaka said. The men only had to work half-days and spent the rest of their time feasting on oysters on the beach, swimming, hunting ducks and fishing. They dried fish and sent them to their friends in the 100th back in Wisconsin. They were given rations of beer because the water was too sulfurous to drink.

After a couple of months, the Army was eager to inspect Prestre’s progress. In January 1943, he organized a demonstration that underwhelmed the officers in attendance. One colonel described the performance as “somewhat of a vaudeville animal act.” Prestre had completely failed in his effort. Although dogs continued to be trained on Cat Island as messengers, scouts and casualty dogs, the attack dog program was scuttled.

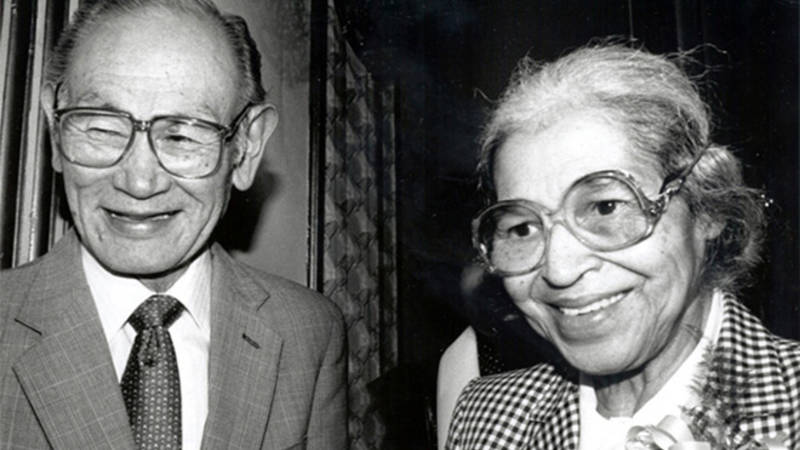

The Legacy of Fred Korematsu

He fought against his forced imprisonment, all the way to the Supreme Court. Today, the National Park Service helps interpret the dark history behind World War II incarceration camps.

See more ›The soldiers of the 100th Battalion went on to prove their valor in combat in Europe. The unit sustained so many casualties that it became known as the Purple Heart Battalion. “They were really the vanguard,” said Isami Yoshihara, the lead docent of the 100th Infantry Battalion Veterans group. “If they’d failed in their mission to prove that they were good soldiers and prove they could be trusted, I don’t want to guess where we’d be today as people of Japanese descent in the United States.”

In September 1943, two months after he married, Nosaka was sent to Italy. While his wife’s parents were incarcerated at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, Nosaka was wounded in combat. He managed to crawl into a cave to escape the firefight. As he hid, a dog appeared at the cave’s entrance.

“I was so happy. I called to the dog and the dog came and kept me warm,” Nosaka said. And then I thought of how I used to treat the dogs. And here, he just kept me warm. After that, he disappeared. I don’t know where he went.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Nosaka was rescued the next day. Once he recovered, he was sent home to Hawaii. He received a Purple Heart, a Bronze Medal and a Congressional Gold Medal.

His daughter, Ann Kabasawa, said the service of the 100th Infantry Battalion illustrated the soldiers’ patriotism on behalf of all Japanese Americans. “There’s this saying in Japanese, ‘okage sama de,’” Kabasawa said. “It means, ‘because of you I am.’ They opened the doors for all of us. They really paved the way. We’ll forever be grateful for that.”

Kabasawa said her father never forgot Cat Island. When he died in 2014, at the age of 98, he had the scar of a dog bite on his forearm.

“Every time he would talk about it, he would still cry,” Kabasawa said. “That’s how it was. They had to prove their loyalty.”