Spring 2024

One Animal’s Trash…

Dung beetles perform invaluable ecological and janitorial services, but their influence has long been overlooked. In Great Smoky Mountains, researchers are finally giving much-deserved attention to the mighty insects.

For months, Maggie Mamantov traveled to points high and low in Great Smoky Mountains National Park to set up traps in the park’s forests and meadows. The traps consisted of simple plastic containers that Mamantov buried in the soil, but the key to her trapping success was the bait: tennis-ball-size spheres of cow dung.

Say Bees!

Sam Droege’s stunning photos of national park insects are the bee’s knees. (And all the other parts, too.)

See more ›Dung beetles are not as celebrated as the park’s black bears and elk, but they arguably play as important an ecological role as the park’s larger denizens — they clean up after them. To a dung beetle, mammals’ droppings are everything. Some beetles nest and mate directly in dung piles or patties, and most adults feed on feces. But more importantly, several species bury excrement — along with the seeds it contains — underground, aerating the soil and moving nutrients where they’re needed. “Their role in the nitrogen and phosphorus cycling is really important,” said Mamantov, who recently published the results of her survey of dung beetles in Great Smoky Mountains with Kimberly Sheldon, her colleague and then-doctoral adviser at the University of Tennessee. “And you know, there’s a lot of dung being produced in the park.”

For more than 25 years, scores of scientists have participated in a massive and unparalleled effort to document every single species in Great Smoky Mountains, from microbes to towering tulip trees, but until Mamantov’s survey, nobody had conducted a formal inventory of dung beetles in the park. Mamantov was especially interested in determining the relative abundance and distribution of nonnative species. Decades ago, European dung beetles were introduced by cattle ranchers and federal and state agencies to various parts of the country. The insects have since spread to other areas, and some scientists are concerned that they might be squeezing out native species. Given the crucial roles dung beetles play in the park, it’s surprising they’ve received so little attention, said Will Kuhn, the director of science and research at Discover Life in America, the nonprofit that supervises the All Taxa Biodiversity Inventory project that has cataloged more than a quarter of the estimated 60,000 to 80,000 species in Great Smoky Mountains. At the same time, “it’s not that surprising, just because there aren’t that many people in the world that work on dung beetles,” he said.

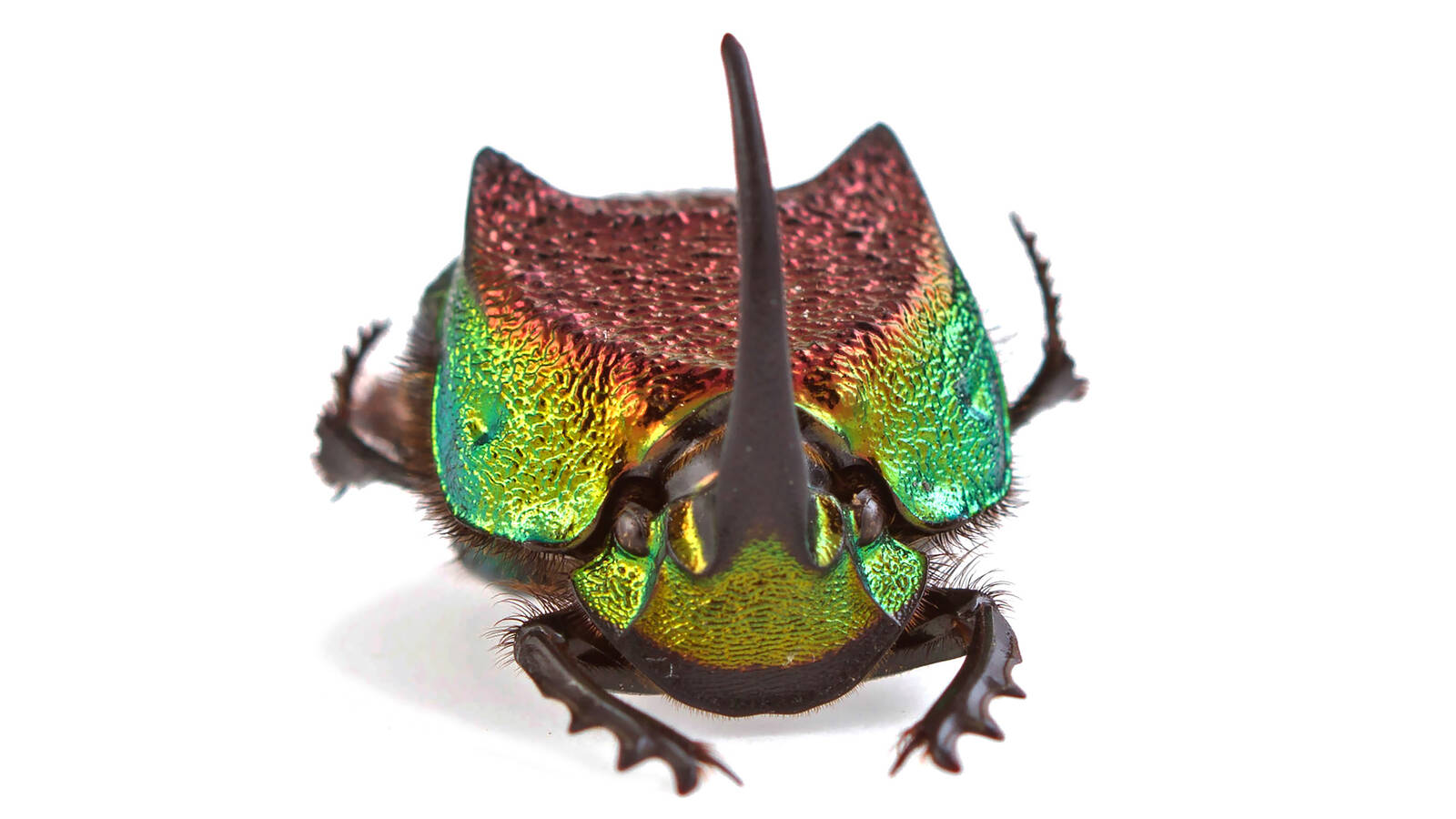

Rainbow scarabs, one of Great Smoky Mountains National Park’s dung beetle species, bury their so-called brood balls deeper as temperatures rise, perhaps indicating that they’re adapting to climate change.

PHOTO BY ALEJANDRO SANTILLANAOnthophagus taurus, a nonnative tunneling beetle, has been hailed as the strongest insect in the world.

COURTESY OF DAN MELEMost dung beetles lay their eggs in dung, which serves as a food supply for the larvae, but species fall into three so-called guilds based on their breeding behaviors. Dwellers leave the dung in place and reproduce there, but tunnelers dig right underneath the patty and bring pieces of it down the hole. Rollers also bury the dung, but only after they’ve shaped it into a perfectly spherical ball and rolled it to a suitable location with their muscular middle and hind legs. (One Onthophagus taurus, a tunneler, was hailed as the strongest insect in the world after it pulled 1,141 times its own weight — the equivalent of an adult human pulling six double-decker buses full of passengers.) That rolling behavior drew the attention of ancient Egyptians, who reportedly believed that Khepri, the scarab-faced god, similarly rolled the sun across the sky.

The services beetles provide are especially helpful to cattle ranchers, as cows produce large amounts of dung spread over relatively concentrated areas. “Cattle in particular don’t like to graze around their dung,” Mamantov said. “And so having the cow patties move underground faster means there’s a larger percentage of the grazing land that is suitable for cattle.” In addition, by breaking down patties, beetles reduce breeding grounds for flies and other parasites and help decrease their populations. But while the benefits of nonnative dung beetles to the cattle industry are well documented, questions remain about the possible drawbacks of imported species.

A depiction of a scarab at the Egyptian Temple of Hatshepsut.

©GARY COOK/ALAMY STOCK PHOTOFor her survey, Mamantov collected cow dung from organic dairy farms and heated it up in the lab to avoid introducing damaging microorganisms into the park. “It makes the whole building smell bad,” she said. (Dung beetles relish omnivores’ feces — Mamantov said she often finds beetles in her dogs’ poop, and some researchers have used human excrement as bait — but she said she avoided those varieties because they are more likely to carry pathogens.)

Over the length of the beetles’ active season, from April through September, Mamantov and a field assistant set up traps every two weeks at six sites and collected the beetles after about 24 hours. (That schedule was disrupted on occasion as some curious bears ripped the traps apart.) After identifying the captives, Mamantov would release the beetles on the spot except for a few specimens destined for the park’s collections. In all, Mamantov collected 403 beetles ranging in length from a few millimeters to nearly an inch. Some sported horns, and coloration varied from black to the multihued body of the rainbow scarab. She collected representatives of nine different species, seven of them native to the region. Individuals of one nonnative species, Aphodius fimetarius, made up more than half of all collected beetles and were found only at high elevations. (The other nonnative species identified was the herculean O. taurus.)

Given the limited historical data, it’s impossible to know whether the relative abundance of nonnative beetles means they’ve displaced native ones. Mamantov said some introduced species have the capacity to produce larger populations and process dung faster than their native counterparts, which, while it might sound like a good thing, could also lead to a loss of biodiversity. “I do think they have the ability to outcompete, or at least cause declines of native species,” she said.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Mamantov’s survey does not offer clues into whether or how the park’s beetles are affected by climate change, but she said research in Europe has shown beetles shifted their ranges in response to warming, so it’s possible that shift is also taking place in the Smokies. Also, Sheldon, who has studied dung beetles and their thermal tolerance for nearly two decades, conducted an experiment where she placed fertilized female rainbow scarabs in mini-greenhouses and found that they buried their brood balls deeper as the temperature increased, thereby insulating their larvae from both higher temperatures and temperature variations. The beetles’ reproduction could still be affected negatively in other ways, Sheldon said, but “it’s encouraging to know that they’re responding in a way that appears adaptive.”

Still, a warming climate could favor nonnative species at the expense of native ones — with unknown consequences for the ecosystems. In a separate study, Mamantov and Sheldon used halogen lightbulbs to mimic warming’s impact on the breeding of two of the park’s dung beetle residents and discovered that the offspring of O. taurus (the nonnative one) survived at a much higher rate than those of the native Onthophagus hecate.

“A lot of the traits that make invasive species good at invading also help them respond to climate change,” said Mamantov, who is interested in further studying the effects of competition between nonnative and native dung beetles. “To me, those types of things are worrying.”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.