Winter 2024

The Long and Winding Recovery

The Anacostia River and the national park site that flanks it were long mistreated and neglected. Are the tides finally turning?

Like many in his generation of Washington, D.C., natives, Alan Spears frequently sped over the Anacostia River in a car as a child, but that was about as close as he got to the waterway, even though it curled by his neighborhood on its way to the Potomac, the city’s more famous river. “The Anacostia seemed to be just this thing that was there,” said Spears, 59, who grew up “east of the river,” in local parlance. “I would hear stories from time to time about the dangerous water quality. … It seemed to be almost more of an impediment than a body of water or a resource.” His parents never brought him to Anacostia Park, the 1,100-acre national park site that hugs the river as it eases its way through Washington.

The Forgotten March

The 1932 veterans’ protest in Washington had a lasting impact on America but disappeared in the dustbin of history. The Park Service is working to change that.

See more ›“It was a dying river that people couldn’t even physically interact with,” said Christopher E. Williams, president and CEO of the Anacostia Watershed Society, a nonprofit that has been working to restore the river for more than 30 years. Those who so much as touched the water would immediately scrub with soap, and the park was underutilized and unsafe.

Back then, the woes of the 8.5-mile-long Anacostia seemed almost insurmountable — and downright horrifying. Due to the city’s insufficient, old water infrastructure, a huge amount of raw sewage would effectively get dumped into the river after storms. River dredging and the construction of seawalls and dry land along the river banks, a project that began in the 1890s, had stolen wildlife habitat and wiped away thousands of acres of marshland, a natural flood buffer. The trash constantly knocking around in the water was not just bottles but everything from grocery carts to refrigerators. Moreover, industry along the riverbanks — including the Navy Yard, the globe’s largest naval arms manufacturer during World War II — had left behind a toxic stew. “You really just have to think of the Anacostia as having been an industrial waste stream,” said Doug Siglin, the former head of the Anacostia Waterfront Trust.

Keith Spence said he sometimes likes to come down to the Anacostia River after work to play his guitar.

©TYRONE TURNERHarmony Buckett, 10, jumps rope at the Anacostia Park skating pavilion, a beloved gathering place in the park — and the only skating rink in the park system.

©TYRONE TURNERJazmine Thomas, left, and Ashley Rodgers at Friday Night Fishing, a free, catch-and-release event hosted by Anacostia Riverkeeper during the summer months. When a temperate evening suddenly turned stormy, they were reluctant to leave because they were having such a good time. They were the last pair out on the dock.

©TYRONE TURNERCapturing nature at Kenilworth Park & Aquatic Gardens, part of Anacostia Park.

©TYRONE TURNERMakhi Smith, 19, (left) and Malik Terrell, 20, practice their instruments underneath the Whitney Young Memorial Bridge, which spans the river near the defunct Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium.

©TYRONE TURNERRoller skaters line dance at the park’s skating pavilion.

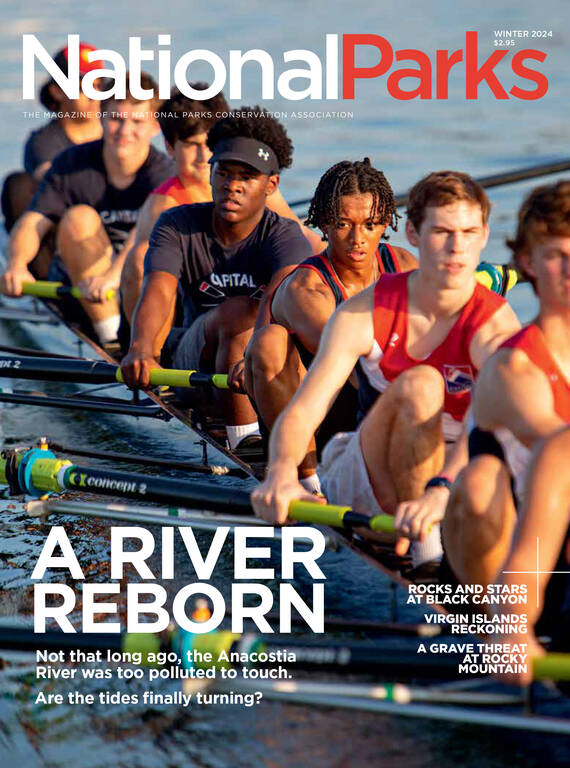

©TYRONE TURNERMembers of the Capital Juniors Rowing team practice on the Anacostia River.

©TYRONE TURNERThe river and the park offer ample opportuntities for recreation, from fishing and paddling to biking and skating.

©TYRONE TURNERYouth with the Anacostia Watershed Society’s Saturday Environmental Academy participate in a tree planting along the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail.

©TYRONE TURNERSkating at Anacostia Park.

©TYRONE TURNERA tai chi class practices in the park.

©TYRONE TURNERMembers of the Capital Juniors Rowing team.

©TYRONE TURNERIt was hardly a coincidence that a river flowing through majority-Black neighborhoods suffered from decades of institutional neglect, activists say. To make matters worse, the nearby coil of highways made it difficult for locals to stroll over, and the river served as Washington’s version of the tracks, exacerbating race and class divisions in the city.

It’s been a slow upstream battle since those muddy, dark days, but the tides are finally turning for the Anacostia River and Anacostia Park, whose health and well-being are inextricably linked. “The stars have aligned, and everything is headed in the right direction, which is amazing to see,” said Ed Stierli, Mid-Atlantic senior regional director at NPCA, which has joined other advocacy groups, community members and political leaders to lobby for the waterway and the park, home to the waterlily-strewn Kenilworth Park and Aquatic Gardens and a beloved outdoor roller-skating pavilion.

Among the most significant advances is an update to the region’s antiquated sewer system. The construction of four massive tunnels, a multibillion-dollar project slated for completion in 2030, will drastically reduce sewage overflow into the city’s three main waterways — Rock Creek, the Potomac and the Anacostia. The Anacostia tunnel system, which opened in 2018 and was completed in September, is already closing in on the goal of capturing 98% of those overflows. The watershed society, which began measuring the health of the river in 1989 by looking at factors such as E. coli levels and submerged aquatic vegetation, gave the waterway a passing grade for water quality for three of the last six years, a monumental shift after handing out F’s for decades.

You really just have to the think of the Anacostia as having been an industrial waste stream.

Visitors can see — and smell — the changes for themselves. Vegetation is returning, fish populations are up, and other animals are also coming back, including otters and beavers, whose presence is auspicious because both species are sensitive to water quality. At the same time, trash traps and cleanup efforts have cleared much of the visible pollution from the water, and new docks have improved accessibility. To date, nearly 20 miles of the Anacostia Riverwalk Trail are complete, and the planned 11th Street Bridge Park will eventually include playgrounds, gardens and a community education center. Through the Great American Outdoors Act, a cluster of Washington parks (including Anacostia) recently received $11.8 million. In Anacostia, the money will be used for rehabilitating facilities and recreational amenities, among other projects.

On a weekday afternoon this fall, evidence of these rising fortunes was on full display. Skaters, from wobbly beginners to pros floating through graceful spins, circled in the pavilion. Along the river trail, people skateboarded, ran, biked, walked dogs or just watched the lazy pulse of the river. Flocks of birds swept in and out of the shaggy greenery along the banks. The river is notoriously murky, but the water almost shimmered in the distance under white clouds.

“It ain’t Rock Creek, but we’re getting there,” said longtime resident Tijunna Williams, who was on a walk with a friend, referring to the waterway and eponymous park that run through a higher-income swath of the city and historically have received more attention and care.

Building (on) Bridges

For nearly a century, Anacostia Park in Washington, D.C., has served as a playground for area residents while also preserving a critical shoreline area and protecting the natural scenery and…

See more ›For the last decade, the rallying cry of the watershed society has been a swimmable, fishable river by 2025. But now that the deadline is approaching, it’s increasingly clear that it won’t be safe for people to eat their catch without limits by then, CEO Williams said. Legacy chemicals trapped in the riverbed are a hazard for fish, and the fixes, which could include dredging or covering toxic hotspots, are tremendously expensive and slow. A swimmable river, on the other hand, is a goal within reach. This summer, the nonprofit Anacostia Riverkeeper planned an event billed as as the first permitted river swim in 50 years. Unfortunately, “Splash” was canceled because the Anacostia River tunnel was temporarily disconnected for work on another tunnel, causing a marked drop in water quality. Bad weather subsequently scuttled the backup event. Boosters see the near-miss as an encouraging marker, however. “It’s not to be understated how exciting it is that we can even be hosting an event like this,” said Quinn Molner, director of operations at Anacostia Riverkeeper, adding that they are now planning a June makeup date.

Still, convincing locals to take a dip is another matter. “Baby, they better not go in that water,” Tijunna Williams said shortly before the second cancellation. She remembers when there were tires everywhere and cars in the mud and who knows what at the bottom. “If there is a bottom!” she added.

The presence of wildlife, such as this great egret and otters, are auspicious signs of a rebounding ecosystem.

©TYRONE TURNERThe Anacostia River stretches for 8.5 miles, carving through the 1,100-acre Anacostia Park in southeast Washington, D.C.

©TYRONE TURNERKenilworth Park & Aquatic Gardens delights visitors year-round. Brave the heat of summer for a true spectacle: the blooming of the park’s lilies and lotuses.

©TYRONE TURNERThat sort of reluctance is understandable, said Christopher Williams, but he believes it can be overcome with education and outreach. He pointed out that making the river “boatable” seemed like a pie-in-the-sky goal when the watershed society was founded, and now people row and paddle there without a second thought.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Meanwhile, the work, the dreaming and the worrying continue. Some true believers picture a day when adjacent neighborhoods have unfettered access to the park. Others are pondering how to maintain hard-won conservation gains in the face of climate change. And the future of the defunct RFK Stadium on the west bank continues to preoccupy community members and activists, who see a proposed new NFL stadium and mega-development as either a looming disaster for the river or a potential boon to nearby neighborhoods. Any new development raises a timeworn question: How do you ensure longtime residents are reaping the benefits as the waterway and park blossom, and rent, property taxes and other costs rise? “I don’t want the very people who have lived with the environmental degradation of the river for the past 50 years to be displaced when the river starts to recover,” Christopher Williams said.

Spears, NPCA’s senior director of cultural resources, no longer resides near Anacostia Park, but his mother still lives in the house he grew up in. Even so, he never had visited the park with her until a sunny day last spring, when his mother turned 97. He wheeled her to the river, where he made a video of her taking a short walk. “She liked being down by the water, and she liked being out among people,” Spears said. “At its most basic, that’s exactly what we want that kind of resource to do for people.”

About the author

-

Rona Marech Editor-in-Chief

Rona Marech Editor-in-ChiefRona Marech is the editor-in-chief of National Parks, NPCA’s award-winning magazine. Formerly a staff writer at the Baltimore Sun and the San Francisco Chronicle, Rona joined NPCA in 2013.