Winter 2024

The Little Fish That Could

The Big Bend gambusia were down to three fish. A difficult — but remarkable — recovery ensued.

In the beginning were Adam and Eve — and Steve. The year was 1957 A.D., and the three diminutive fish, presumably christened by one of the biologists who cared for them, were given a monumental task: to save their species.

Salvation was by no means assured for the Big Bend gambusia, a fish whose entire range at that point had consisted of just two locations, both within Big Bend National Park. One of the two springs that were home to the gambusia had dried out in the 1950s, so staff rushed to collect several fish from the other pond, which was being overrun by aggressive invasive competitors. Early reintroduction efforts failed, and biologists were left with just the three, which were kept in a tank in Austin. Gambusia have a life expectancy of about a year, so time was running out. A refuge pond was built quickly, the three survivors were released in it, and park staff hoped for the best.

Troubled Waters

For decades, biologists and anglers stocked national parks with nonnative trout. What will it take to undo the ecological damage?

See more ›There would be more brushes with extinction for the gambusia over the following decades, and plenty of threats to their existence remain to this day. But the plucky little fish have benefited from the assistance of generations of park stewards and other allies. While the gambusia are not out of the proverbial woods (or cattails), their population now numbers in the thousands, and their near-term future is no longer in doubt.

“I think we’ve done a lot for this fish,” said Thomas Athens, the park’s wildlife biologist, “and without the park and the Fish and Wildlife Service and all these people that were involved in this in the beginning, this fish wouldn’t be here. It just wouldn’t.”

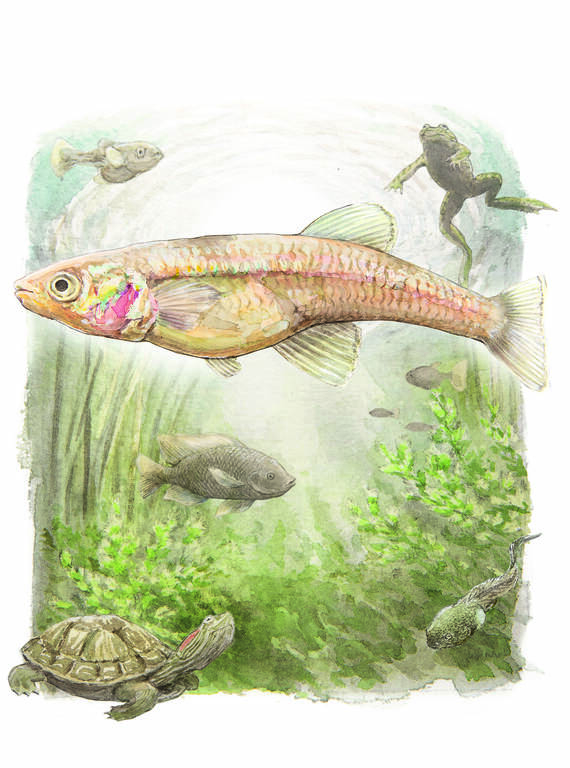

The Big Bend gambusia is, all things considered, a plain-looking fish. It’s less than 2 inches long and is silvery-yellowish in color with a faint stripe running along its flanks. It is one of a few rare species of desert fish (such as the Devils Hole pupfish residing in Death Valley National Park) and the only endangered fish in Big Bend, according to Athens. The species was first collected in 1928 by naturalist Frederick Gaige from a marsh near the Boquillas hot springs, some 16 years before the park was created. The gambusia thrives in water temperatures between 92 and 95 degrees Fahrenheit, so even under the best circumstances, its range never extended much beyond a couple of warm springs, but its precarious situation took a turn for the worse when western mosquitofish were found to have invaded the gambusia’s limited territory. The mosquitofish is native to other parts of the U.S., but it was introduced in water bodies across the country starting in the early 20th century because of its appetite for mosquito larvae. It turns out mosquitofish also enjoy eating the aquatic invertebrates that make up most of the gambusia’s diet, and they’ve outcompeted the gambusia in all but the warmest parts of the ponds they have shared.

Mosquitofish don’t seem to prey much on gambusia, but other fish do. In the 1960s, campers apparently dumped a couple of predatory green sunfish into one of the ponds in a misguided effort to be helpful, and nonnative blue tilapia have encroached on gambusia territory at least twice, including in 2008 when the flooding waters of the Rio Grande brought the undesirable fish all the way to the gambusia’s habitat. A precipitous drop in temperature can also be deadly, and a cold snap in 1975 caused a massive gambusia die-off. (An insurance population of gambusia was established at a hatchery in New Mexico in 1974, but gambusia there also kept dying in the winter until managers figured out they needed to keep the fish in warmer water.) Of course, without water there is no gambusia, so if the springs that feed into the fish’s ponds were to dry out because of groundwater overuse or a detrimental change in rainfall patterns, the consequences would be catastrophic. “If we somehow lose that water, that spring water, then these fish won’t survive,” Athens said.

Without the park and the Fish and Wildlife Service and all these people that were involved in this in the beginning, this fish wouldn’t be here. It just wouldn’t.

To their credit, wildlife managers quickly realized the gambusia needed help if it were to survive these unfavorable odds. The species was listed under the Endangered Species Preservation Act of 1966, the precursor to the landmark Endangered Species Act. Park staff built the first refuge pond in 1957 and created a second one in 2007. Both are fenced in to keep errant livestock and humans at bay, and one is equipped with an electric pump that adds warm water to the pond. Park managers also shifted the water source for the Rio Grande Village campground to a well farther away from the ponds to minimize the potential impact on the gambusia’s springs. Other actions designed to help the gambusia have included decommissioning a service road and burning nonnative vegetation.

Comeback Bears

How black bears crossed an international border and miles of desert to recolonize Texas’ Big Bend National Park.

See more ›A few years ago, the park also enlisted the help of Sean Graham, then a biology professor at Sul Ross State University, to monitor the gambusia population. Graham recruited a few motivated graduate students and made many two-hour trips to trap and count gambusia and measure the ratio of gambusia to mosquitofish where both coexisted. While there, Graham and his team also endeavored to improve potential gambusia habitat in a nearby ditch by trapping and removing the creatures that didn’t belong there — from mosquitofish to tilapia, red shiners and red-eared slider turtles. Unfortunately, that work came to a halt during the pandemic when Graham and his family moved to Australia, his wife’s country of origin. Leaving the gambusia behind was not easy. “I really kind of fell in love with the gambusia and was really looking forward to kind of making a difference with those guys,” said Graham, a herpetologist who now works for Ozfish Unlimited, an Australian fish conservation organization.

In the meantime, the gambusia hasn’t been hung out to dry. Park staff go out every year to remove excessive vegetation from the ponds, and Athens recently completed an agreement with curators at the ichthyology collections of the University of Texas to create a survey protocol and resume monitoring gambusia next year.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Additional threats loom, including climate change’s uncertain impact on water availability and a disease Graham spotted in a few specimens caught outside the refuge ponds. While the gambusia can continue to count on a few dedicated souls, it can also tap into its own survival skills. Graham was shocked during his surveys to find that some gambusia had persisted in a pond overtaken by all sorts of predators and competitors. “They’re battlers,” he said.

Kelsey Wogan, one of the graduate students who accompanied Graham on his gambusia-monitoring outings, said the gambusia’s best chance is to continue doing what Adam, Eve and Steve — and their countless descendants — did so well: multiply.

“One thing that makes me hopeful for the Big Bend gambusia is they are good at procreating,” she said.

“They’re not like the giant panda.”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.