Fall 2023

Battle Lines

For decades, advocates have defended Manassas National Battlefield Park from one threat after another. Now with the specter of a massive data center project looming, they may be facing their biggest fight yet.

Kyle Hart, clad in a vest and boots, a blade of grass between his lips, gestured to the surrounding fields and described a war. He identified the players, called out decision-makers for incompetence and reckless choices, and stressed the importance of holding the line.

Though the land on which we stood was steeped in Civil War history and hallowed by soldiers’ blood, that’s not the battle Hart, NPCA’s Mid-Atlantic program manager, was railing about. He was referring to a modern-day brawl between local preservationists and international developers. “This is the biggest, most impactful land use decision in the history of northern Virginia,” he said.

I might have been skeptical of Hart’s rhetoric if I hadn’t spent the previous month learning about Manassas National Battlefield Park’s latest foe: the Prince William Digital Gateway. The innocuous-sounding name pertains to a proposal that would turn more than 2,100 acres of farmland adjacent to the park into a corridor of data centers with a square footprint the size of three Pentagons (or more if developers hit their maximum development capacity). Current plans call for 40-odd warehouses, climbing 70 or more feet in the air. Chock-full of hot, humming servers that run 24/7, data centers are designed to ensure uninterrupted access to all the digital trappings of our 21st century lives — from emails and streaming TV to podcasts, Zoom meetings and social media posts.

These buildings aren’t just eyesores — they’re energy and water hogs. Each data center relies on diesel generators in the event of power outages, can consume as much water as a town of 50,000 people and can burn through 10 to 50 times more electricity than a typical office building. Nearly a quarter of the energy supplied by Virginia’s largest electric utility goes to data centers.

During my research, I’d spoken to passionate, angry and confused advocates, all determined to fend off the development. It’s not straight NIMBY-ism, they argue. Most understand the societal demand for data centers but believe that the unregulated industry needs guardrails. Maybe, they say, these things shouldn’t be placed near homes, schools or parks. NPCA is one of the groups pushing for a full-scale examination of the impacts of the industry. That understanding could then inform standards about where to put data centers, how to build them and what measures to take to best protect people and the environment.

“You can’t save everything everywhere, and nobody’s arguing that,” said Jim Campi, chief policy and communications officer for the American Battlefield Trust, which owns a 20-acre parcel within the proposed corridor. “You certainly need data centers. This is just a really poor choice of a location.” The larger Manassas landscape functions as vital recreation space and wildlife habitat, Campi said, and it preserves Civil War history as well as the story of the Reconstruction era, when Native Americans and freed slaves established settlements and cemeteries in the area. These archaeological resources, some of which still need documentation, could vanish if bulldozers rumble through.

“You’re looking at a site that is mentioned in social studies books across the country,” said Blaine Pearsall, a member of the Prince William County Historical Commission. “Who’s making the decision to say we’re willing to give this up so that we can have this particular industry in this location?”

Ostensibly, the decision rests with the county board of supervisors, but Pearsall’s question points to the flurry of political machination, uncertainty, mistrust and fear surrounding the project. According to Hart, a data center corridor at the scale being considered would turn the countryside adjacent to Manassas into something resembling the New Jersey Turnpike. It would financially benefit those selling to the developers but would undo decades of work by historians, neighbors, recreationists and Congress, he said.

I considered that comment as I stood on the brow of a hill within the park. It was spring in Virginia, and the battlefield, 5,000 acres at the outermost edge of Washington, D.C., sprawl, was alive with birdsong and filtered sunlight. I’d expected to glimpse the orderly grid of a neighborhood in the distance, but fields, forest and fence lines stretched to the horizon. A few cannons served as a visceral reminder of what took place some 160 years before.

Manassas commemorates not one, but two Civil War battles. In July of 1861, around 60,000 Union and Confederate soldiers clashed in what many consider the first major battle of the war. “It was the first chance that these armies got to test each other,” Hart said. The Confederate victory convinced the Union that the rebel uprising they hoped to quash quickly would be a long and protracted affair. The second battle, just 13 months later, fits within a larger three-week campaign that concluded at Antietam with the war’s deadliest one-day battle.

Birds on the Battlefield

As green space shrinks and suburbs expand, a growing number of wildlife seekers are heading to historic parks for their nature fix.

See more ›To place the Battle of Second Bull Run (also called the Battle of Second Manassas) in context, I reached out to Gary Gallagher, emeritus director of the University of Virginia’s John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History. Union forces had achieved a series of coups that spring, taking Nashville and New Orleans and threatening Richmond, the Confederate capital. Had the Confederates — led by Stonewall Jackson and Robert E. Lee — not been victorious in the Seven Days Battles near Richmond, and then at Manassas in August, the war might have concluded with a brokered peace. “It would have been a restoration of the Union as it had been before,” Gallagher said, meaning the South could have continued with business as usual, that is, with nearly 4 million people still enslaved. That was news to me: I’d never considered a Civil War without an Emancipation Proclamation. Gallagher spoke a little more about this precarious moment before emphasizing the park’s role as a classroom. “You can’t understand any of these battles by reading maps and even reading the best prose about them,” Gallagher said. “You have to go to the places.”

While the park protects much of the land involved in these two engagements, it doesn’t cover it all. In 2006, the federal government identified a Manassas Battlefield Historic District spanning more than 6,400 acres; roughly 1,300 acres lie outside park boundaries and along Pageland Lane, the epicenter of the proposed development. There, in the sultry heat of 1862, troops prepared for yet another clash. Nurses and doctors established field hospitals. And there, too, lie the unmarked graves of a few hundred soldiers who died of a measles outbreak.

Some of the proponents of the data center, including landowners set to make upward of $1 million an acre by selling to the developers, say that this area has lost its rural character because of a long-existing transmission line or because traffic has increased on the road at the heart of the proposed corridor. It’s true that the power structures loom over the fields and dawdling tourists might get passed by other motorists, but there’s no mistaking the pastoral feel, preservationists say. While driving on Pageland Lane to reach the park, I spotted horses grazing, and the biggest building visible was a barn. And on our trek across Brawner Farm, a corner of the park that witnessed some 22,000 injuries and deaths, Hart and I saw no one, but spied the tracks of deer and raccoon intermixed with those of horse and hiker. At one point, Hart squatted down and pointed out the skinny, three-pronged track of a female turkey in still-wet mud. “This one’s real fresh,” he said.

Past is Prologue

Ann Bennett, land use chair for the Sierra Club’s Great Falls chapter, calls this recent data center proposal the “fifth battle of Manassas.” Five, I learned, may be a conservative number.

Manassas faced its first threat, in the form of housing development, within a decade of its 1940 establishment. Park staff managed to secure a boundary expansion, pulling more acreage under the park’s umbrella of protection, before dodging the next curveball: the routing of Interstate 66. Then, in the 1970s, Marriott Corp. proposed a “Great America” theme park catty-corner to National Park Service land. History buffs recognize the nearly 500-acre site for its association with General Lee, who set up shop there on Stuart’s Hill during the second battle. Despite its import, the property lay beyond park borders. The board of supervisors thought a simple rezoning of the area would clear the way for the project and boost the county tax base. But a legal challenge to the hasty rezoning effort and a federal request for an environmental impact study pushed the company to abandon its amusement park plans.

Park proponents didn’t really have their resolve tested, though, until 1986 when a developer targeted the same wedge of land for an office park and a 1,000-home subdivision. Rolland Swain, then the Manassas superintendent, raised his concerns with the developer, John T. Hazel, who made a series of concessions to appease the Park Service and residents, from halving the number of homes to limiting building height. When Hazel failed to secure an office tenant, however, he changed tack, scrapping the original plan in favor of a 1-million-square-foot mall. The incongruity of a giant shopping center at the doorstep of a historic battlefield outraged locals. NPCA took a stand against the development, and the National Trust for Historic Preservation followed suit. Soon the threat to Manassas made national headlines.

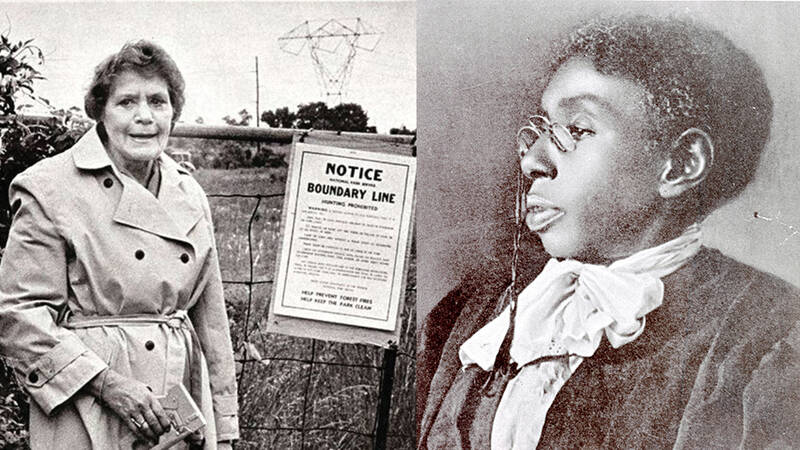

Annie Snyder fought for decades to protect the Manassas battlefield from a series of threats (left). Right: Jennie Dean, a woman born into slavery along Pageland Lane, started Manassas Industrial School for Colored Youth after being emancipated. Some critics say the data centers would make it difficult to preserve the area’s

African American history.

Annie Snyder, a seasoned preservationist who was then owner of Pageland Farm — 185 acres within the Manassas Battlefield Historic District — stepped into the fray. Her Save the Battlefield Coalition organized a public rally with protesters sporting “Stonewall the Mall, Save Manassas” buttons. They also conducted a door-to-door blitz, securing over 75,000 signatures that Snyder presented to Congress.

In November of 1988, after Hazel had broken ground, Congress finally took action, passing a bipartisan bill that absorbed those 500-some acres into the boundaries of the national park. Gordon J. Humphrey, then a New Hampshire senator, said he found it difficult to approve the move as a conservative Republican, “but it seems warranted in this emergency case.”

The loss of Chantilly (the neighboring county’s only Civil War battlefield) to development, and the near loss of a piece of the Manassas battlefield mobilized like-minded groups and helped shape the modern preservation movement, Gallagher said. The timing was fortuitous, as another threat would soon require this newly forged collective to fine-tune their organizing skills.

Kathryn Kulick had just moved to the area when she heard that Disney planned to open a theme park near Manassas. “If anybody does a good job of being secretive about acquiring land, it’s Disney,” she said. Kulick, who today serves on the county’s historical commission, described how Disney quietly snatched up land before announcing in 1993 their vision for a 3,000-acre “Disney’s America” amusement park less than 4 miles from Manassas battlefield.

You can’t save everything everywhere, and nobody’s arguing that. … You certainly need data centers. This is just a really poor choice of a location.

The county (and the state) embraced Disney’s proposal, which included a history-based theme park, as well as resort hotels, a campground, a golf course and over a million square feet of retail space. “Disney seemed unstoppable,” author Joan M. Zenzen wrote in her book “Battling for Manassas.” But then, the president of the National Trust for Historic Preservation decried the development in a column published in The Washington Post, and renowned historian David McCullough began volunteering his time for the cause. Donations from the likes of the du Ponts and Mellons funded lobbying trips to Virginia’s capital, where advocates — including representatives from the Sierra Club and the Piedmont Environmental Council — spoke ardently about the importance of preserving the still-rural landscape. Wealthy landowners, intent on keeping the anticipated hordes of Disney visitors at bay, exerted their considerable influence. Snyder and about 100 others even protested at the “Lion King” opening in Washington.

As public awareness grew, so did support for preservation. Disney’s plan involved funneling visitors through a Civil War-era village before they could hop on steam trains to explore other periods of American history. Such a simulacrum sounded reasonable to some, but others found the Disneyfication of history offensive, and one attraction, designed to make park-goers experience life as a slave, especially rankled. “Eleanor Holmes Norton”— the D.C. congressional delegate — “and some other elected officials said, ‘You’re going to do what?’” Kulick recalled.

Eager to save its image, Disney backed out of its plan in 1994.

Kathryn Kulick called the recent expansion of data center proposals a “vicious problem” in northern Virginia and believes the Manassas battlefield will never

recover if the digital gateway moves forward. “There is no doubt in my mind: It will destroy that park,” she said.

Though the Washington suburbs continued to accelerate toward the town of Manassas and its famous park over the next two decades, the area around the battlefield escaped relatively unscathed. That was largely due to the county’s 1998 adoption of a comprehensive plan that identified a “Rural Crescent” with 10-acre minimum lot sizes. Kulick called the Rural Crescent, which was established to prevent rampant subdivisions and promote agricultural use, “the most effective land use planning tool ever.” (The Rural Crescent was abolished last year when the county updated its comprehensive plan.)

Then in 2012, a plan for a parkway gained traction. The initiative centered around expanding Pageland Lane from a two-lane road into a commuter thoroughfare. The county, hoping to sway the Park Service, promised to close two existing routes through the battlefield to non-park traffic in exchange for the park’s support for the new road. Even though the proposal would have paved 4 acres of the park and an additional 12 acres of historic district, the Park Service backed the plan.

NPCA and park neighbors challenged the development. This time, Snyder’s daughter Page led the charge. “Our front two fields lie in the path of the proposed bi-county parkway,” she said at a 2013 rally. “In those fields are two Civil War mass burial sites and likely many other undocumented graves. We cannot pretend that they are not there, and we cannot disrespect them.”

A government shutdown, a change in administration and a regulatory snag ultimately relegated the parkway to the collective backburner. (Unsurprisingly, the data center plan requires expanding Pageland Lane, further provoking opponents who call the parkway a “zombie” road for its inability to die.)

Data Center Mania

In 2021, the first rumors of a data center corridor started circulating. At that point, northern Virginia already claimed the title of data center capital of the world, with Loudoun County — Prince William’s northern neighbor — boasting the highest concentration of the new-age warehouses, around 26 million square feet powered by Amazon, Google and Microsoft, among others. And while Prince William seemed destined to be next, park advocates hoped the proximity of the battlefield, the area’s designation as a historic district zoned for agriculture and its position within the Rural Crescent would lead the county government to dismiss the digital gateway idea out of hand. Instead, the board of supervisors jumpstarted the approval process, ushering in a period of marathon public meetings and reviews from an alphabet-soup of local and state agencies.

In a matter of months, the initial scale of the corridor ballooned from some 800 acres to over 2,000. Brandon Bies, then-superintendent at the park, penned a letter to Prince William Board of Country Supervisors Chair Ann Wheeler, calling the project “the single greatest threat to Manassas National Battlefield Park in three decades.” (Wheeler, a vocal supporter of the data centers, could not be reached for comment.)

To this day, the plans and players remain cloaked in secrecy. Questions about basic facts, such as the anticipated number and location of buildings, have swirled and gone unanswered. Nondisclosure agreements between decision-makers, landowners and the developers were signed. The county archaeologist’s finding that full build-out could result in the destruction of the cultural landscape was omitted when it came time to give presentations to the public, and no one knows whom to blame. “It’s an atrocity how this stuff happens,” Kulick said.

Last November, less than a year after Bies’ fiery rebuke of the project, the board of supervisors adopted an amendment to the county’s comprehensive plan, propelling the project forward. Now, the board must decide whether to rezone the acreage. If that happens, 100 willing landowners are teed up, having already signed contracts with QTS Realty Trust and Compass Datacenters, the developers, who didn’t respond to National Parks’ queries.

In an unexpected twist, not only are Page Snyder and her neighbor MaryAnn Ghadban (allies in the fight against the parkway) among those selling, but they are spearheading the effort, according to local news outlets. “Without question,” a 2022 Prince William Times article stated, Snyder and Ghadban “started the ball rolling.” Wearied by decades of fighting to protect their farms, foreseeing a continued erosion of the area’s rural character, and lured by the cash, they organized landowners and courted a willing developer, according to the story. (Ghadban, who declined to comment, cited hesitancy over speaking to a magazine affiliated with NPCA. Snyder couldn’t be reached, but she wrote in a letter to a Virginia senator that there is “no future in farming” on Pageland Lane.)

High Stakes

Scrambling to match the pace of this highly secretive industry, NPCA and its allies hired consultants, commissioned studies, reached across party lines and established working groups. Kulick helped form a regional homeowners association umbrella group whose members represent some 150,000 households. The goal, she said, is to educate and inform the public: “There’s so many people that don’t even know.”

Elena Schlossberg compared data center developers to 21st-century robber barons. “They absorb the tools of government and the levers of power so that they can operate in ways that totally cut out citizens,” she said.

©ERIC LEECritics say the data centers would threaten water quantity and quality (via impervious surface runoff and sedimentation, for example), contribute to air pollution and exceed the limits of the power grid. On that last point, Elena Schlossberg, founder of the Coalition to Protect Prince William County, is particularly passionate. “When the data center industry talks about green energy, it makes me just want to throttle someone, because there’s no amount of solar or wind that will ever compensate,” she said. A 2015 study partially funded by the International Energy Agency states that each data center consumes about as much as 25,000 homes, so “we are going to have to rely on more coal and more natural gas in order to meet the demands,” Schlossberg said. This could derail Virginia’s goal of 100% renewable energy by 2050 and entail construction of additional substations and transmission lines financed by ratepayers.

Another worry for those opposed to the project is its potential impact on the cultural resources of the area. Schlossberg reminded me that significant historic events unfolded here during the era of Reconstruction. She spoke about Jennie Dean, a woman born into slavery, who established an industrial school after emancipation to help freed men and women achieve economic freedom as well. The developers have indicated a willingness to reserve a small plot for interpreting the African American history in the area, but Schlossberg says that’s inadequate: “It deserves more than a plaque,” she said. “Who’s going to walk a trail amidst data centers and AC generators and transmission lines and substations? Nobody.”

Data centers also emit a hum that Dale Browne characterizes as a “noisy, miserable thing to live next to.” A retired IT director for a global financial telecommunications company, Browne understands the role data centers play in modern society. He’s also the president of a Prince William homeowners association that abuts four new Amazon data centers, so he’s well-versed in where they don’t belong. His community is situated near a municipal airport, train tracks and a highway, but the nonstop, low-frequency noise of data centers is categorically different than the sounds of that other infrastructure, he said. After the first few buildings went online in 2022, residents began complaining of headaches and heightened stress. They told him they had to move their babies’ nurseries and home offices into their basements. “People hear it through their walls, can feel it in their walls,” Browne said.

Keep Massive Industrial Data Centers Away from our National Parks

New developments could compromise the environmental integrity of several national parks in Virginia, including Prince William Forest Park, Manassas National Battlefield, Wilderness Battlefield, and more.

See more ›And yet, the developers’ master corridor plan continues to highlight recreation. Illustrations depict trails wending through the outskirts of the digital gateway, and promotional photos show families exploring lush forests. The developers pitch the plan as having the potential to “fulfill unmet community needs,” which perplexes their adversaries who point out that the park currently offers 40 miles of trails and the adjacent state forest boasts an additional 5. Figures on early maps indicated that 800-some acres of “open space” would result from the development, but Hart calls that “intentionally nebulous.”

“The only open space that is actually being delivered by this development is land that isn’t buildable anyways,” said Hart. In short, it’s undevelopable floodplain. And the two large parks present in early plans were absent from the developers’ most recent application. Hart called those “hollow promises made by the developers to ram this project through the approval process.”

Data center proponents, including several county supervisors, frequently cite local jobs as a prime benefit of the development. But one supervisor, Bob Weir, calls foul. “I’m not buying the PR campaign — a very expensive PR campaign — that the people behind the gateway are putting out,” Weir said. He believes most of the construction jobs will go to specialized crews from out of state. Once the data centers are operational, possibly in 2030, “you’ve got more security guards than you have technicians,” he said. (The developers estimate that the buildings — which eventually could number 40, though that figure remains in flux — might each create 10 to 20 jobs. While opponents question this accounting, it’s still a far cry from the thousands of jobs Disney promised in the ’90s.)

The planning horizon for the National Park Service is 500, 1,000 years. … But we’re dealing with decision-makers at the local level who often don’t have a planning horizon that extends much beyond the next election.

One of the central issues with data centers, in the view of John Hennessy, the retired chief historian of Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park and an authority on Manassas history, is the lack of third-party, empirical analysis of the industry’s long-term impact. “And you’re going to experiment on park boundaries?” he asked. “It just makes no sense to me.”

Hennessy said it comes down to a difference in mission and perspective between the Park Service and the local government. “The great challenge of managing a national park in the Eastern United States,” he said, “is that the planning horizon for the National Park Service is 500, 1,000 years. … But we’re dealing with decision-makers at the local level who often don’t have a planning horizon that extends much beyond the next election.”

Holding the Line

Using lessons learned from previous Manassas campaigns, NPCA and its allies are pulling out all the stops to defeat the latest threat. The county’s volunteer-based historical commission is picking apart flimsy archaeological, noise and viewshed studies while formulating comments on the rezoning applications. They’ve also proposed the inclusion of two farms within the federally recognized historic district — and the data center corridor — as county registered historic sites, a status that should convey added protection. Kulick’s homeowners group has joined civic organizations from neighboring jurisdictions to draft construction and design standards for data centers that they anticipate bringing to Fairfax, Fauquier, Loudoun and Prince William counties for adoption. These would dictate everything from height and noise limits to siting requirements.

Last fall, a coalition tried to pass bills in the Virginia General Assembly that would initiate a statewide evaluation of industry impacts and prohibit the construction of data centers within 1 mile of a national park unit. None succeeded.

Despite the setbacks, public sentiment seems to be swinging in favor of preservation. In a recent NPCA-commissioned survey, 86% of northern Virginia residents said they would support legislation that would place a data-center-free buffer around park sites. This is welcome news for those counting on this November’s election to upset the pro-data center balance on the board of supervisors.

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

Back at Manassas last May, Hart regaled me with tales of sledding behind the park’s Stone House as a child and reminisced about getting engaged on a hill above Bull Run. On the way back to our vehicles, he pointed to the green leaves of some waist-high milkweed, reminding me that monarch butterflies exist because of this very plant. Then, he shifted his focus back to the issue at hand. If we allow data centers next to a national park site, in a nationally recognized historic district, he said, then the industry will essentially have carte blanche to do whatever it wants, wherever it wants. “If this industry is going to get reformed,” he said, “it starts right here.”

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.