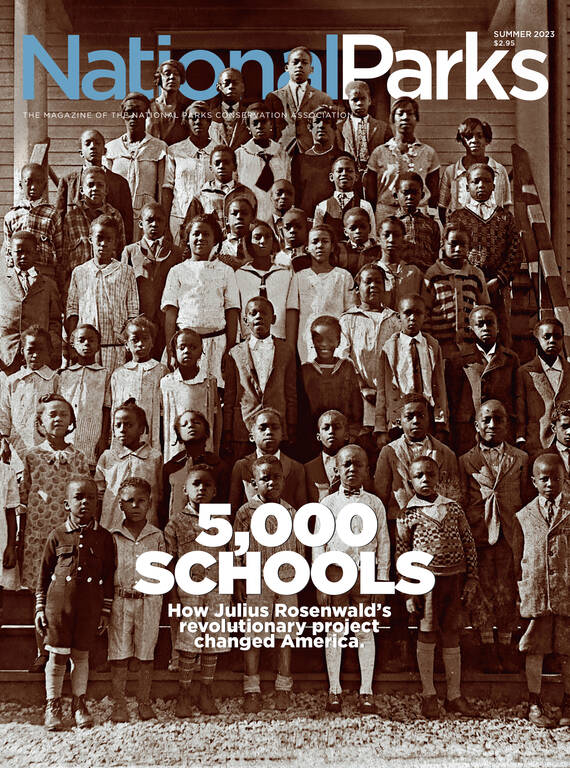

Summer 2023

Second Take

A decade ago, a flawed exhibit about the Sand Creek massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho angered the Tribes. This time, the museum took pains to get the story right.

For decades, Gail Ridgely has worked tirelessly to make sure one of the worst atrocities ever committed on U.S. soil was never forgotten.

In the 1990s, Ridgely, his father and other Tribal members joined historians and archaeologists on the plains of southeastern Colorado in a quest to identify the exact location where, in 1864, U.S. Army troops slaughtered more than 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho people — most of them women, children and elders. Even after the site was found and Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site was established in 2007, Ridgely, a former teacher, school principal and Tribal college president, has continued to educate county governments, universities and other institutions on the story of Sand Creek and his Northern Arapaho Tribe. “It’s not necessarily a mission,” Ridgely said. “It’s something that has to be done.”

In the process, Ridgely has logged many miles traveling to Colorado from his home in the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. This past November, he hit the road again to celebrate another major milestone: the opening of an exhibit about Sand Creek shaped by the very people who, like Ridgely, are the descendants of the victims and the survivors of the massacre. “Healing happens, and healing today right now has happened, and I feel good about it,” Ridgely said. “I think about that on those long drives.”

The birth of the History Colorado Center’s “The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal that Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever” was not an easy one. The museum, which is run by History Colorado (a state agency and charitable organization that collaborates routinely with the national park site), unveiled a different version of the Sand Creek exhibit in 2012 but did so without meaningful consultation with Cheyenne and Arapaho people. The Tribes were incensed. They said the display downplayed the massacre as a collision of cultures, and they decried errors and omissions. Shannon Voirol, the director of exhibit planning at the center and one of the developers of the new exhibit, said staff were working on too many exhibits for the museum’s inauguration of a new building and relied on older scholarship for the earlier Sand Creek show. “There’s a long tradition of us working in that consultation, and there was one important big mistake, where we didn’t,” she said. “Before and after, we did.”

Tribal representatives asked for the exhibit to be taken down. The museum obliged, and it was shuttered in 2013, just one year into what was supposed to be a multiyear run.

The Tribes’ reaction to the exhibit and the museum’s willingness to listen are indicative of a larger conversation among museums, schools, news organizations and others about whose stories are appropriate to tell and who should do the telling, and the cursor in that debate is moving relatively rapidly. Alexa Roberts, the former superintendent of the national historic site and now the interim chair of the Sand Creek Massacre Foundation’s board of directors, said that public discourse about the story of the massacre was much more divided not long ago. “Some segments of the public continued to defend the U.S. Army’s actions at Sand Creek as being appropriate and necessary at that period of time, while other segments of the public felt strongly that telling the true story of the atrocity and its consequences was way overdue,” Roberts said. “History Colorado, as a state institution, was trying to thread a fine line through these polarized public perceptions and expectations.”

As the new exhibit tells the Sand Creek story, gold seekers and others moved to the Territory of Colorado in ever-increasing numbers in the years leading up to the massacre. In the area of today’s Boulder, Arapaho people let the newcomers spend the winter, but they overstayed their welcome. “They never left,” said Fred Mosqueda, a Southern Arapaho culture and language coordinator who worked on the new exhibit. “Instead, we were forced to leave.” Treaties were signed and broken, and Tribes found themselves starving on a small fraction of their former homelands. Meanwhile, John Evans, the governor of the Colorado Territory, made no secret of his animosity toward Native Americans when he issued in August 1864 a proclamation authorizing citizens of Colorado “to kill and destroy” any “hostile Indians” and plunder their property. Despite Evans’ proclamation, Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle held out hope that peace could still be achieved, and hundreds of Cheyenne and Arapaho people settled by Big Sandy Creek near Fort Lyon after receiving assurance from Evans that they’d be safe.

When Col. John Chivington and his troops arrived on that cold morning of November 29, Black Kettle pointed to the white and U.S. flags raised over the camp, but the soldiers ignored the peace gesture and brutally murdered as many people as they could. Witnesses told of soldiers bashing in children’s skulls and cutting unborn babies out of their mothers’ wombs. The slaughter continued for hours, and when it was done, the perpetrators cut scalps and other body parts from their victims and displayed them in a victory parade on the streets of downtown Denver — near where the History Colorado Center now stands.

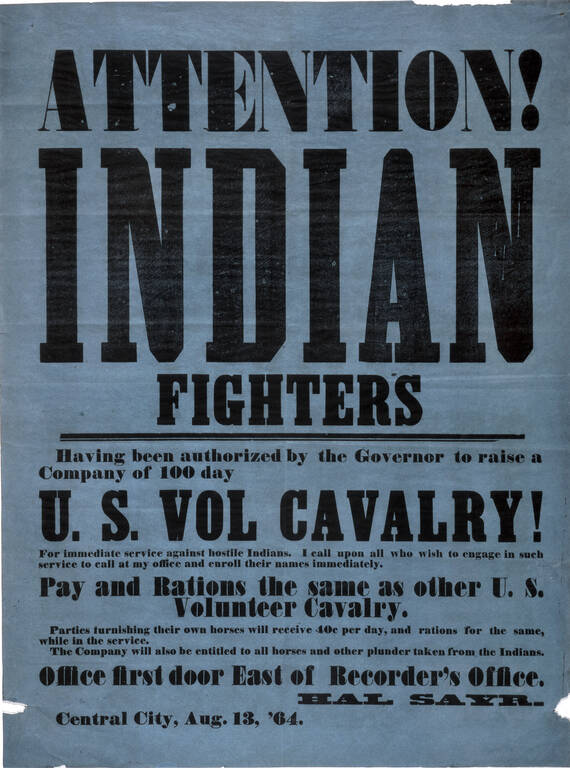

A recruitment poster for Colorado’s 3rd Cavalry.

COURTESY OF HISTORY COLORADOFederal inquiries found Chivington and Evans responsible, but they suffered little hardship as a result. Chivington was never actually punished, and Evans, who did resign from his governorship, served as chairman of the board of trustees of the University of Denver, which he had founded. Meanwhile, Capt. Silas Soule, one of the soldiers who refused to participate in the massacre, was killed on the streets of Denver a couple of months after giving his testimony. For some survivors of Sand Creek, history repeated itself when on November 27, 1868, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led a surprise attack on their camp by the Washita River in what is now Oklahoma. Custer’s men killed up to 60 Cheyenne, captured women and children, and burned lodges, food and clothing. Black Kettle was among those killed that day.

Former Sen. Ben Nighthorse Campbell, who led the effort in Congress to establish Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site, said there were over 100 massacres of Native American people during the country’s history. “A lot of them are not recorded, but Indian people know about them,” he said.

Against a historical backdrop that also included forced cultural assimilation, discrimination and restricted access to resources and services — not to mention the blunder of the first Sand Creek exhibit, mistrust ran high when museum staff reached out to the Tribes. “When you first come to work with some institutions, it’s always been like, ‘Well, we want to see what you say, but we already know what we’re going to do,’” Mosqueda said. But the museum staff, at the instigation of then-Gov. John Hickenlooper, set out to regain their Tribal partners’ trust. They also wanted to enlist their help for what would become the current Sand Creek exhibit. “For many reasons, we decided to keep at it with the Sand Creek story,” Voirol said. “One of the largest ones is that it’s a huge part of how Colorado became Colorado.” Many phone conversations, Zoom calls and in-person meetings — in Colorado, Wyoming, Oklahoma and Montana — followed. It worked. “It was simple because everyone was in a positive mood to move on,” Ridgely said.

We’re Still Here

Every national park site sits on ancestral lands. So what does it mean to be a Native American working for the Park Service today?

See more ›Every detail was discussed and ultimately approved by Tribal representatives, Voirol said. “All those words were really workshopped and thought about and tried on,” she said. “Words matter. Whether you say settlers or invaders, there is a big difference.”

The new exhibit is twice as big as the first one. It opens with photographs of the annual 173-mile healing run from the massacre site to Denver. The introduction makes it clear whose voices are telling the story: “They wanted to wipe us out, but they failed,” it reads. “We are survivors, and we remember what happened to our loved ones.”

The exhibit, which includes audio translations in Cheyenne and Arapaho as well as in Spanish, features three parts: one about the Tribes’ history and culture before Sand Creek, one about the massacre told on black panels, and one about the Tribes’ lives today. That last section is important, said Mosqueda, who remembers encountering someone at an Indigenous Peoples Day celebration in Boulder who told him he was the first Arapaho she’d ever met. “It struck me, because this is, this was our homeland, and yet we’re not here and people don’t even know who we are,” he said. “They don’t know we’re still alive, so this allows us to tell them a little bit about where we are, what happened to us and how we got there.”

The day before the exhibit opened to the public, the museum was closed so that Ridgely, Mosqueda and many of their relatives, friends and fellow Tribal members could have “the place to themselves to say and do what they needed to do,” Voirol said. Some listened to the voices of their late relatives recorded in oral history interviews. Others couldn’t hold back tears. “It really, really struck home that, you know, our story was finally being told honestly,” Mosqueda said.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›In recent years, Cheyenne and Arapaho welcomed other signs of progress: Hickenlooper issued a formal apology for the massacre on Colorado’s behalf in 2014, and two years ago Gov. Jared Polis finally rescinded Evans’ 1864 proclamation.

Other efforts to tell a fuller Sand Creek story are underway: Roberts’ foundation is gathering documents and other materials related to Sand Creek from institutions across the country and will make them available to descendants, scholars and visitors at a research center near the park. An effort to rename Mount Evans is in the works, and Mosqueda and others are pushing for the name of Washita Battlefield National Historic Site to reflect what he says was not a battle but a massacre.

“The thing you have to realize is that, yes, it’s been over 150 years,” Mosqueda said. “But how long has it been since we were allowed to start to work on these things? Not very long.”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.