A proposed large-scale wind farm would mar the land surrounding Minidoka National Historic Site, considered a somber place for reflection by Japanese American survivors and descendants. NPCA and Friends of Minidoka are fighting the project.

Minidoka National Historic Site was added to the National Park System in 2001 to preserve part of a World War II incarceration site where families of Japanese heritage were displaced, separated and isolated from other Americans. For many Japanese American families, this and similar sites are places for healing trauma and loss, and a way to ensure our country doesn’t bury or hide our history, even when it’s difficult to tell.

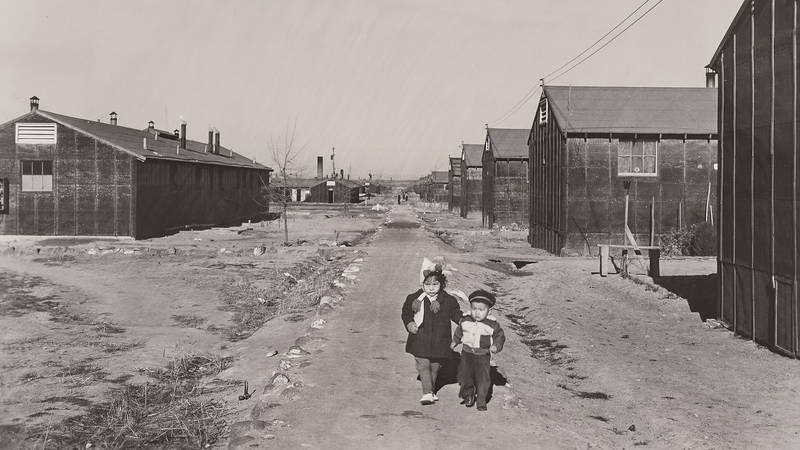

Following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered people of Japanese descent across the West Coast to be forcibly removed from their communities and the businesses they owned to incarceration sites. Because of fear and hysteria, more than 122,000 people were moved to faraway sites such as Minidoka War Relocation Center in south central Idaho — never to return home.

The U.S. government chose Minidoka as an incarceration site for its extreme remoteness and isolation. Incarcerees have described how the expansive, unobstructed landscape intensified their feelings of loss and isolation.

A developer’s plan for a large-scale energy site north of the park unit — marked by hundreds of wind turbines, transmission towers and related infrastructure — would forever alter visitors’ experience of the landscape and their understanding of how it contributed to the pain of those who were incarcerated.

That is why NPCA and Friends of Minidoka are calling on the Bureau of Land Management to establish a 231,000-acre boundary, called an Area of Critical Environmental Concern, to preserve the cultural and historic viewshed, landscape and traditional uses of the land surrounding Minidoka.

The reconstructed guard tower and sign at the entrance of Minidoka National Historic Site.

NPS/Stan HondaApproval of this protected area would build on nearly 50 years of official U.S. government acknowledgements that the incarceration of Japanese Americans and Japanese Alaskans during World War II was unconstitutional.

While NPCA supports responsibly-sited renewable energy, we want these projects developed in the right places, in the right ways and with public support — without harming the historical and cultural resources and values of the National Park System and public lands. The proposed Lava Ridge project, as it is known, does not meet these criteria.

If the Bureau of Land Management were to let the wind farm move forward, the agency would also be going against its own policies, which state a commitment that when making decisions “[f]air treatment means that no group should bear a disproportionate share of the adverse consequences that could result from federal environmental programs or policies.” Advancing the wind project at its size and scale ignores the pain and suffering of the Japanese American survivors, families and community, and forces them to bear the consequences of a government decision that overlooks the cultural and historic lands where their families suffered, worked and overcame prejudice.

An American Journey

Was the story of Minidoka National Historic Site his story, too?

See more ›As NPCA and Friends of Minidoka wrote in a recent letter to the Bureau of Land Management, “Any decision … that impacts the Greater Minidoka viewshed would damage Minidoka’s ability to serve as a place for learning, commemorating, and healing for the Japanese American community, the Asian American Pacific Islander community, and the nation as a whole.”

“You wouldn’t build a huge wind project over another concentration camp, or Gettysburg, or the Washington Monument,” Robyn Achilles, executive director of Friends of Minidoka, told The Washington Post. “It really is a somber location.”

13,000 lives upended

Between 1942 and 1945, 13,000 Japanese Americans and other residents from Oregon, Washington and Alaska were incarcerated at Minidoka. The War Relocation Center covered approximately 33,000 acres land and included 36 residential blocks, each with 12 barracks, a mess hall and latrine. All the buildings were cheaply built with tarpaper and inadequate plumbing and sewage systems.

President Bill Clinton established the Minidoka Internment National Monument in 2001. In 2008, Congress redesignated the monument as the Minidoka National Historic Site and expanded the park boundary based on National Park Service recommendations.

Minidoka survivors and descendants visit the park site often — particularly during the annual Minidoka Pilgrimage in the summer — to commemorate the travesties and foster the community’s continued resilience and survival. They consider the site sacred, a place to heal multi-generational trauma that has flowed through the community for decades. The site has deep connections to communities, schools, friends, jobs, businesses, houses, pets and neighborhoods lost forever because of racism and prejudice.

Remoteness and dark skies disrupted

The National Park Service has expressed concern that the Lava Ridge Project would fundamentally change the psychological and physical sense of remoteness and disrupt the dark night skies central to the Minidoka experience.

Simulations by the Bureau of Land Management show a wall of wind turbines more than 500 feet tall would be visible from places throughout the site — including its visitor center, barracks, Honor Roll built in reverence to the young men and women from Minidoka who served in the U.S. military, and multiple stops where visitors are encouraged to stop and reflect.

The visual impacts would be significantly worse in the morning, when the turbines would be backlit by the rising sun, according to Bureau of Land Management models.

Analyses in Western states by Argonne National Laboratory also indicate turbines’ passing blades can create “glinting” — a brief, often repeated flash of light seen from miles away, typically at the turbine’s hub — and a strobe effect as shadows of turbine blades repeatedly fall on their towers when the sun is low.

While the Bureau of Land Management has proposed alternative plans that are smaller in scale than the developer’s original proposal — 269 to 378 turbines instead of 400, for example — NPCA and Friends of Minidoka believe these alternatives aren’t sufficient to protect the visitor experience.

A chance to keep Minidoka as it is

The Bureau of Land Management expects to make a decision on our request for a boundary to protect this sacred landscape later this year.

Preserving Minidoka is critically important in respecting Japanese Americans and Japanese Alaskans and their late-parents, grandparents and family members, many of whom served in the military despite the prejudice and discrimination shown them.

We owe it to these survivors and their descendants — and all Americans — to keep Minidoka as it is.

Listen to NPR’s coverage of this issue

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

About the author

-

Kristen Brengel Senior Vice President of Government Affairs

Kristen Brengel Senior Vice President of Government AffairsAs the Senior Vice President of Government Affairs, Kristen Brengel leads staff on public lands conservation, natural and cultural resource issues, and park funding. Kristen is responsible for implementing our legislative strategies and working with the administration.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Northern Rockies

-

Issues