Fall 2022

Paradise Found?

A century ago, a college student in “cavewoman” attire reportedly braved bears, freezing temperatures and a bearskin-clad suitor in the wilds of Rocky Mountain National Park. Did any of it actually happen?

After a night at an inn in the shadow of Longs Peak, Agnes Lowe, a 20-year-old college student from Michigan, prepared to spend a week alone in the backcountry of Colorado’s Rocky Mountain National Park. It didn’t take her long. She donned a leopard-skin tunic and headed out toward the wilderness.

She’d have to wait for solitude a little longer, however. Outside the lodge that Sunday in August 1917, Lowe was greeted by Rocky Mountain luminaries, throngs of photographers and nearly 2,000 other people. “The immense crowd — the equal of which never has been seen in this resort — cheered her wildly and shouted all manner of wishes for the success of her strange adventure,” wrote A.G. Birch, a journalist and publicist for The Denver Post.

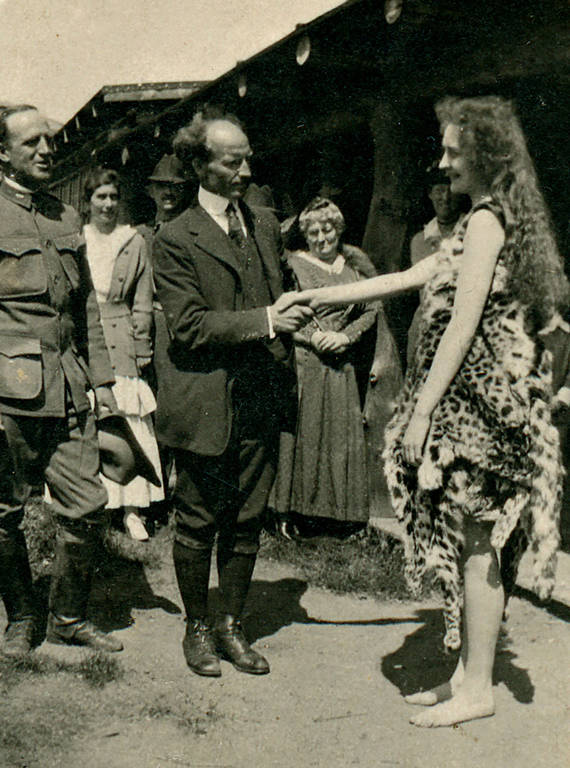

“Modern Eve” shakes hands with naturalist Enos Mills.

COURTESY OF LULIE AND JACK MELTONEnos Mills, the inn’s owner whose campaign for the creation of the park had succeeded two years earlier, accompanied Lowe into the woods for a bit before sending her off toward Thunder Lake in the remote southeastern part of the park, where she would attempt to survive for a week on her own. Lowe had brought no food, weapons, matches or tools of any kind with her, and she became known as “modern Eve” in the Post’s coverage. Lowe’s stated goal was to “escape for a time from the shams and artificialities of modern city life” — still somewhat of a novel idea in the early 20th century — and Birch chronicled her every move in sensational stories that were picked up by newspapers across the country.

Lowe’s August escapade was her second attempt at sticking it out in the sticks. In late July, she had thrown in the towel after enduring two days of thunderstorms and cold temperatures in the park. “Nothing less than a short and ugly word could describe the sensation!” she wrote after her ordeal. Still, she was determined to have another go. “Everyone is taunting me with ‘I told you so’ and other choice remarks. I won’t stand it!” she said. “I’m going to make good this time.”

Inclement conditions threatened to derail her new effort, too. A couple of days into it, Lowe used a piece of charcoal to write a couple of worrying messages (“nearly froze last night” and “tempted to give up but didn’t”) on slabs of bark that she left on a trail for rangers to pick up. But several groups of tourists, perhaps eager to meet “Eve” in the flesh, reported that she seemed to be adjusting to her environment and spotted her drinking from a mountain stream, picking blackberries and “carrying a good-sized string of mountain trout, which she said she had caught without a rod or line.”

Adam won’t think he’s in the Garden of Eden if he comes up here.

Around the same time, Lowe told some other visitors about an encounter she had had with a brown bear. That would be one of two brushes with grizzlies, which have since been hunted to extinction in Colorado. In the second one, she said she came across a sow and two cubs while harvesting huckleberries. Lowe improvised and started to sing a tune that the female bear seemed to appreciate, as she refrained from attacking Lowe. “No debuting prima donna ever watched her audience more searchingly for the first sign of inattention,” she later wrote of her performance. “And none was ever so ready to fly to a haven behind the scenes.”

Even in nature’s midst, it was a fellow human who caused Lowe her biggest scare. A resident of Greeley, Colorado, named George Desouris wrote in a poorly spelled letter to the Post that a vision compelled him to join “this fare young Eve.” Desouris, who called himself “Adam the Apostle” and wore a “moth-eaten bear hide,” might have thought he was a good match for Lowe, but L. C. Way, the park’s superintendent, disagreed and warned that Desouris would be expelled from the park if he showed up. “Adam won’t think he’s in the Garden of Eden if he comes up here,” he said.

Desouris did turn up at the park and soon located Lowe, who screamed when she spotted him and then spent much of a day and a night running — and swimming — away from him. He was eventually captured by two rangers after “a strenuous fight” and handed over to police, who forced him “to don a long overcoat loaned by a kindly tourist” and escorted “Adam” out of the area.

CHANGING TIMES

The rest of Lowe’s expedition proved less stressful. She even met up with Mills and Way, offering them a luncheon of pine bark soup, trout, mushrooms, “chipmunk peas,” wild honey and chokecherries. The discovery of a trail of blood near Thunder Lake raised fears about Lowe’s well-being the day before her expected return, but she arrived back at the inn the following day as planned. She was healthy and had gained, not lost, weight over the course of the week. Awaiting her was a crowd as large as that on the first day, as well as a mail sack containing no fewer than 64 marriage proposals.

Lowe also inspired a man reportedly named Perry Adams, who was wandering on a Denver street, wearing only cabbage leaves and declaring his intention to live in the wilds of Rocky Mountain. The historical record does not confirm whether he followed through. Mills’ takeaway from Lowe’s weeklong outing was arguably a feminist one: “The feminine body will always, I believe, resist the exigencies of nature with more endurance than that of the male,” he wrote. Lowe gave some talks in Denver about her experience and penned her own account in the Post in which she bemoaned having to return to civilization. Then she disappeared from the public eye.

Her odyssey continued to reverberate through the halls of the National Park Service, though. Hearing of what he deemed poor-taste publicity, Horace Albright, the agency’s assistant director, asked Way to explain himself. Way confessed that during Lowe’s week in the wilderness one of his rangers met her at regular intervals, handed her street clothes and took her to a cabin to relax for a couple of days.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Way “wasn’t the least bit regretful or sorry about that,” said author Phyllis J. Perry, who included Lowe’s story in her collection of tales from the park, “It Happened in Rocky Mountain National Park.” “He set out to get attention, and he did.”

So how much of Lowe’s story was true? Probably not much. Some sources say that Lowe’s actual name was Hazel Eighmy and that she was a receptionist at a Denver photography studio. Curt Buchholtz, who researched the park’s history extensively for his 1983 book, “Rocky Mountain National Park: A History,” said the only logical conclusion is that it was staged and designed to promote the new park. “It was a stunt, basically,” he said.

Visitation to Rocky Mountain did more than double in 1917, but how much of that increase can be attributed to “modern Eve” is unclear. And no one knows what became of the young woman named Lowe or Eighmy. While researching his book, Buchholtz tried to locate her or some of her relatives but was not successful.

“I like to think she married one of these Adams,” he said.

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.