Summer 2022

An Alabama Album

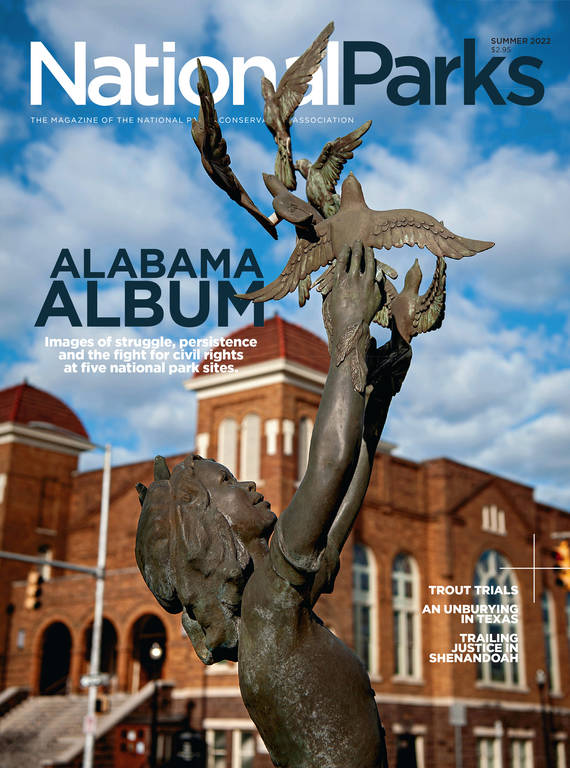

Images of struggle and persistence at five national park sites.

“It is impossible to not picture Alabama when you envision civil rights in America,” advocate Phillip Howard says in “54 Miles to Home,” a short film about the families who invited protesters to camp on their land during the 1965 march from Selma to Montgomery. “Five counties in Alabama have some of the most iconic moments in the history of not only civil rights, but America.”

TUNE IN

The National Park Service recognizes that history and other stories of struggle and persistence at five Alabama park sites: Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, Birmingham Civil Rights National Monument, Freedom Riders National Monument, Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site and Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site.

These sites collectively cast a light on strands of African American history that are not very well known, says Alan Spears, NPCA’s senior director of cultural resources, who was closely involved in the campaign to establish the Birmingham park. Standing in places where horrific acts of violence took place is profound and disturbing, and “it’s changed me,” Spears says. He feels anger, but also an abiding gratitude for those who suffered and advocated for change. “We made progress based on the commitment and force of vision these people had in the ’40s and ’50s and ’60s,” he says.

©KAREN MINOT

Spears makes several other important points: When a park is designated (as Freedom Riders and Birmingham were in 2017), it underscores how significant the events were — not only for locals but “for everyone in the country and for most of the people on the planet.” Also, these Alabama parks lift up the everyday people whose names are not widely recognized but who were essential foot soldiers in the civil rights movement. Finally, reflecting honestly on the past can lead to healing. “We want to be sure we are telling these stories even if they are not always pleasant,” he says. “We need to know about them, and dare I say it, having learned about these experiences, to make sure we don’t repeat past mistakes.” Or as the Rev. Freddy Rimpsey, a civil rights activist whose portrait appears below, puts it: “When the wind blows and the storm comes, we can stand firmly because we know our history.”

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

In February, the magazine sent photographer Rory Doyle to Alabama to capture images of these five sites. He took photos of buildings, museums, murals, sculptures, memorials and visitors. He went to the cities and towns where protesters demonstrated and to the countryside where they marched. And he photographed some of the people who were intimately connected to these monumental events, including a Freedom Rider and a survivor of the bombing at Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church that killed four young girls.

Sometimes, a sculpture glimmering in the sun or the face of a witness can convey something that is beyond words. On the pages that follow are the stories Doyle uncovered during hundreds of miles of travel through the state of Alabama.

—Editors

Carolyn McKinstry at the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama. McKinstry was there on September 15, 1963, when the Ku Klux Klan bombed the church, killing four young girls.

©RORY DOYLEA worker power-washes the Three Ministers Kneeling statue in Kelly Ingram Park in Birmingham. The scene immortalizes the moment in 1963 when clergy members, who were leading a Palm Sunday protest march, knelt to pray when faced with imminent violence.

©RORY DOYLEScrap iron police dogs created by artist James Drake lunge across a walkway in Kelly Ingram Park. Police used attack dogs, fire hoses, tear gas and clubs to disrupt civil rights demonstrations in the 1960s. Thousands of peaceful protesters were arrested and jailed, including more than 600 children.

©RORY DOYLEThe Four Spirits Memorial in Birmingham’s Kelly Ingram Park preserves the memory of the four young girls killed in the 1963 bombing at the nearby 16th Street Baptist Church: Addie Mae Collins, Denise McNair, Carole Robertson and Cynthia Wesley.

©RORY DOYLEA sculpture dedicated to Martin Luther King Jr. stands in Kelly Ingram Park.

©RORY DOYLENia Davis (left) photographs her son, Mason, next to the statue of Martin Luther King Jr.

©RORY DOYLEThe Rev. Freddy Rimpsey, pictured in Anniston, Alabama. Rimpsey, a civil rights leader who supported the Freedom Riders following the attacks in 1961, said that the violence against those riding the buses in protest of segregation laws made him realize “what hate can make a person want to do to another human being. And I made a vow to myself and to the Lord that I was going to spend my life showing what love can do, rather than hate.“

©RORY DOYLEOne of the hangars at the Tuskegee Airmen National Historic Site includes a full-sized replica of a P-51 Mustang, a fighter plane flown by the first Black military pilots in World War II. At that time, Tuskegee was the only military aircraft training program available to African Americans. All told, over 15,000 men and women passed through Tuskegee, becoming technicians, radio operators, parachute riggers, meteorologists and more. Both Tuskegee park sites show that “even in the depths of segregation, lynching and Jim Crow and all the segregation practices, you still had African Americans who were determined to be successful,” Alan Spears said.

©RORY DOYLEThe Edmund Pettus Bridge on the Selma to Montgomery trail. On March 7, 1965, now known as “Bloody Sunday,” several hundred peaceful protesters set out to march from Selma to the state capitol to demand the end of discriminatory voting practices. State and local lawmen brutally attacked the marchers on the bridge, leaving dozens injured. Footage of the violence horrified the nation and galvanized the movement. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965 five months later.

©RORY DOYLEOn March 21, 1965, after gaining court approval for the voting rights protest, thousands of marchers walked more than 50 miles from Selma to Montgomery. Mary Hall-McGuire and Johnnie McGuire hold a picture of Mary’s father, David Hall, a farmer who opened his property to protesters, allowing them to camp on his land and stay in his barn and home. “It was so incredibly brave,” said NPCA’s Alan Spears. Between 1947 and 1965, roughly 50 bombs were detonated in Birmingham by the Ku Klux Klan and other pro-segregation groups, and “the overall feeling in Alabama was that if you participate, you might have a bomb coming to your farm or house.” The portrait was taken in the Hall home.

©RORY DOYLEThe pastoral landscape along the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail in Lowndes County, Alabama.

©RORY DOYLEPhillip Howard stands near the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Howard, a project manager at The Conservation Fund, has spent the last two years working to preserve the nearly forgotten homes and campsites used by protesters who marched from Selma to Montgomery in 1965.

©RORY DOYLEJosephine Bolling McCall’s father, Elmore Bolling, was lynched in Lowndesboro, Alabama, in 1947 for being “too successful” as a Black businessman. Bolling McCall, pictured beside the roadside marker for her father along the Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail, believes acknowledging the truth of lynching in this country is the only way to ensure history does not repeat itself.

©RORY DOYLEFreedom Rider Bernard Lafayette stands outside Tuskegee University’s main library, where he conducted research before joining the voter registration effort in Selma. Lafayette, a co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, was beaten and arrested for attempting to desegregate buses in the South. “When you get as old as I am, you realize that you don’t live forever, you know?” he said. “So we want to get as many people as possible participating and making sure that there’s a movement for social change.” Tuskegee Institute National Historic Site preserves the history of what is now Tuskegee University, a historically Black college founded by Booker T. Washington.

©RORY DOYLEA mural at the Freedom Riders National Monument in Anniston commemorates the civil rights activists who risked their lives to integrate the bus system in 1961.

©RORY DOYLEAlberta Cooley McCrory, mayor of Hobson City, Alabama, stands for a portrait in Anniston, Alabama. McCrory recalls marching in the streets as a teenager in the aftermath of the 1961 bus attacks. “What happened in Anniston is a story that has to be told,” she said.

©RORY DOYLEA visit to Montgomery’s National Memorial for Peace and Justice, managed by a nonprofit, offers a sobering glimpse into the legacy of enslavement and lynching in this country. Atop a grassy knoll, the memorial features 800 coffin-sized, steel slabs, inscribed with the names of more than 4,400 lynching victims. Each slab represents a county where at least one documented lynching occurred.

©RORY DOYLE