Spring 2022

Park Protein

A Chicago-based company has created a new, Earth-friendly protein from a fungus that was accidentally discovered in Yellowstone.

In 2009, Mark Kozubal was a doctoral student at Montana State University, six years into his research of extremophiles — microorganisms that thrive in environments of unusual temperature, pH level or chemistry — in Yellowstone National Park. The research entailed annual excursions in which Kozubal, his fellow graduate students and their professors would lead a team of horses 20 miles to a backcountry base camp. From there, they would set out on foot, sometimes through waist-deep mud, carefully dodging unmapped fumaroles and geysers.

The barren land was painted in hues of red and yellow. Green and black algae grew out of sandy, acidic soil full of heavy metals. Bison filtered in and out of the steam.

“It’s just a magical place to work,” Kozubal said, “like the surface of Mars, but even more colorful.” The environment was so alien, in fact, that NASA was one of several organizations funding Kozubal’s research in hopes of gaining a better understanding of where life might exist on other planets.

One summer day, Kozubal was in the park with a biology class from a Montana high school. Although his research focused on the primitive cellular life in the hottest zones of the hot springs, Kozubal wandered off to inspect an interesting-looking alga growing in the warm rhyolite sand of a geothermal floodplain. At the time, there was much scientific hype about using algae to produce biofuels, so Kozubal put a sample in a flask to take to his lab.

Back in Bozeman, Kozubal tried to cultivate it, but whenever he did, a white fungus took over instead. “I thought, this is kind of a unique-looking fungus,” Kozubal said. “It grows in a cool way. I decided to switch my focus to that.” The fungus grew quickly and robustly in acidic environments. Eventually, Kozubal dubbed it Fusarium strain flavolapis, with “flavus” meaning “yellow” in Latin, and “lapis” meaning “stone.”

At first, Kozubal sought to use the fungus to make biofuels through a company he co-founded in 2012. But in 2015, Kozubal and his co-founders decided there was more promise in turning the fungus into protein.

Kozubal and his colleagues developed a new way to ferment the fungus in trays using a simple sugar substrate, nitrogen and acidic water. They grew the fungus into a mat of interconnected filaments akin to muscle that is 30% fiber and 50% dry mass protein with vitamins, minerals and all 20 amino acids. “It looked like food,” Kozubal said of the result. “There’s lots of precedent for people eating fungi, and it had the nutritional profile that was very desirable and the texture we like.” The team called it “Fy” and renamed the company Nature’s Fynd.

You can’t really solve climate if you don’t solve food.

Fungi have a long history in alternative proteins. The meat alternative called Quorn has been made since 1985 using a fungus from the same genus as the one Kozubal discovered. Startups such as The Better Meat Co., Meati, ENOUGH and MyForest Foods are conjuring “steaks,” seafood substitutes and vegan bacon out of fungi-derived proteins.

Audrey Gyr, a startup innovation specialist with the Good Food Institute, a nonprofit promoting alternative foods, considers ingredients like Fy to be the proteins of the future. “The cost and ability to create proteins at scale is pretty unparalleled,” she said, “and it’s usually far more efficient than using an animal.”

According to the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization, 26% of the planet’s ice-free land is used for animal grazing, and a third of cropland is used to grow livestock feed. Raising farm animals is one of the largest sources of human-induced greenhouse gas emissions, which is why alternative proteins are drawing significant interest from environmentally minded investors.

Fy, a fungus grown from algae collected at Yellowstone, is high in protein and can be formed into meatless breakfast patties.

©NATURE’S FYND“They’re moving beyond electric and solar to see food as a critical innovation,” Gyr said. “You can’t really solve climate if you don’t solve food.”

Last year, the Chicago-based Nature’s Fynd launched its first products — meatless breakfast patties in original and maple flavor, and dairy-free cream cheese, in original and chive and onion. For now, the products are available in Berkeley, California, Chicago and New York City. The company is mum about new products in the offing, but Anderson Cooper recently sampled a Fy yogurt on TV.

Nature’s Fynd is capitalizing on the Yellowstone origins of the fungus behind its protein, but Kozubal’s Ph.D. adviser, Bill Inskeep, who has been studying life forms in Yellowstone’s thermal features for almost 25 years, said fungi of the Fusarium strain can be found elsewhere. In any case, he said, the origin of the fungus has little bearing on the protein it makes.

“Protein’s protein,” Inskeep said. “It’s not like there’s little golden shamrocks in here that make us invincible. Bringing things to market has everything to do with how much perseverance and long-term commitment you have, and sometimes less about the uniqueness of the idea.”

According to Inskeep, many scientific discoveries happen in Yellowstone because the park offers a 2.2-million-acre natural laboratory and an organized permit system for scientists to conduct research. Perhaps the most famous application of Yellowstone research followed Thomas Brock’s discovery of the bacterium Thermus aquaticus in Mushroom Spring in the 1960s. That led to the isolation of the enzyme Taq polymerase, which enables everything from COVID polymerase chain reaction (or PCR) tests to DNA analysis.

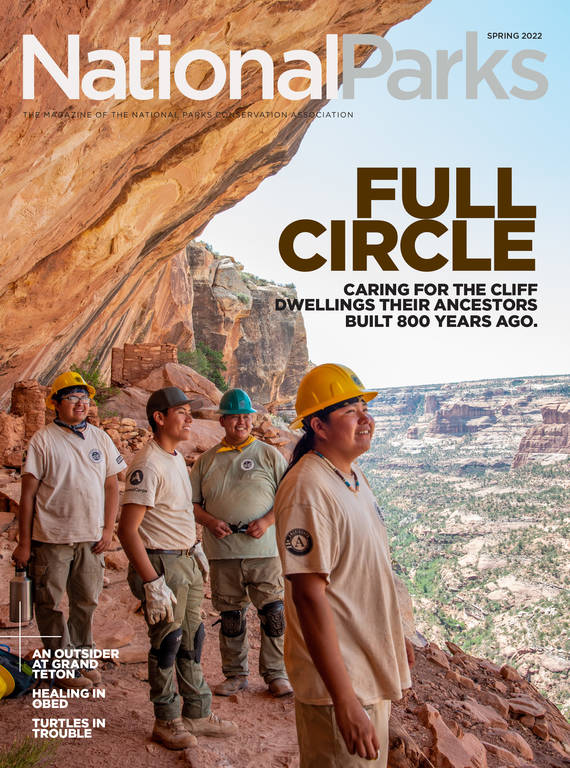

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›In the crowded but burgeoning alternative meat market, Nature’s Fynd has raised more than $500 million from investors such as Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates by presenting its products as healthier and more Earth-friendly than plant-based proteins. Fy uses a fraction of the land, water and energy that traditional agriculture requires and can be made without sun, rain or soil. The company regenerates all the fungus it needs without having to collect more from Yellowstone.

Whether this fungus has the global impact of Thermus aquaticus or is merely a flash in the pan will depend on how Fy is received by consumers. “At the end of the day,” said Nature’s Fynd CEO Thomas Jonas, “if you’re making food, it better taste good.”

My family and I had the chance to find out when Nature’s Fynd mailed me a box of its products. One Saturday morning in January, I cooked up a hearty breakfast of eggs, maple and original breakfast patties, and bagels slathered with both original and chive and onion dairy-free cream cheese. Our disobedient dog begged at my feet, an endorsement tempered by the fact that he also eats mouth guards, used tissues and socks.

We gathered around the table and took our first bites. The cream cheese was soft and spreadable and tasted very much like cream cheese. The breakfast patties were a little dry, with a texture that reminded me of tempeh. The flavors were inoffensive, if not transcendent. Our 7-year-old, Theo, nibbled a breakfast patty and ventured a lukewarm opinion. “It tastes a bit vegetably,” he said. Later, though, when I brought our dishes into the kitchen, I could see he much preferred it to his eggs.