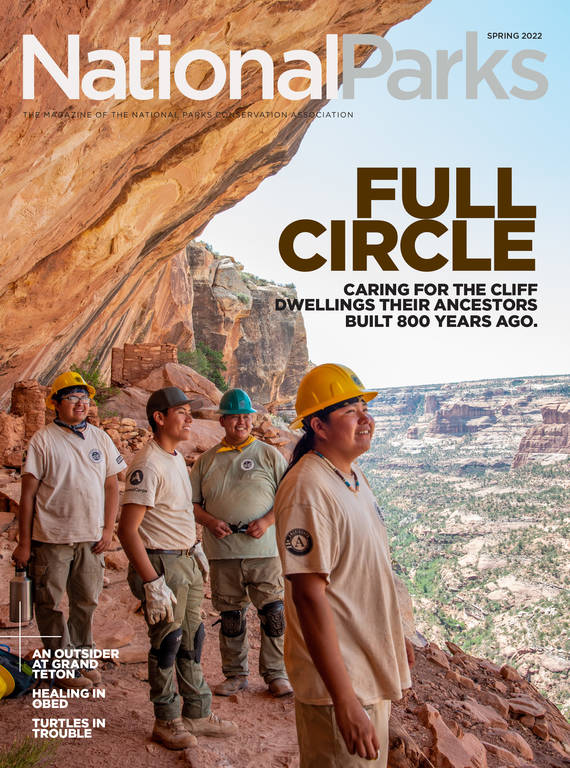

Spring 2022

Lofty Heights

We were young, brown outsiders in the world of outdoor adventure. Climbing Grand Teton marked a turning point.

One September morning in 1979, I stood on the summit of Grand Teton with my friend, Mark Martinez Luna, ecstatic. The sun was shining, immense views stretched before us, and we were young, strong and fearless. A pair of 23-year-old Chicanos far from our normal lives and manual labor jobs back in Denver, we had just sprinted up the Grand in style and surprisingly good time. Mark and I had spent most of a week climbing other peaks in the Tetons backcountry, but the Grand was the climax. In every sense, we were on top of the world.

I have thought a lot about the climb over the years. Whenever I visit Grand Teton National Park, I can hardly take my eyes off that breathtaking crag. I stare up at the highest point of the range, marveling that I once stood on its summit and boring my family again with the story. It was a pivotal experience at a time when I was just finding my way in the world of outdoor adventure — a world that was even less welcoming to people of color than it is today.

I don’t know that we realized it at the time, but on some unconscious level, Mark and I felt we had something to prove, not just to ourselves, but to some of the people around us. The challenge was social as well as physical. In the last couple of years, as society has grappled more openly with complex issues of race and class, all this has come into sharper focus. I more clearly see the barriers I faced as a young brown man from an underprivileged background trying to find my place in a very white field — and how I made my way despite the obstacles. It was a lot like a successful climb: I had to choose the right line, make every move count and push my limits to get there.

A week before summiting the Grand, we had driven from Denver to Wyoming in my ratty old patchwork Volkswagen Beetle, hoping the whole way it wouldn’t overheat. As we pulled into Jackson Hole and got our first view of the legendary mountain range, “Whoa” was about all we were able to articulate. We had both already been bitten by the climbing bug. Knowing what we were in for, we looked at those enormous, jagged peaks with a mixture of dread and desire.

The trip was part of the Colorado Outward Bound School’s Minority Field Staff Training Program. The trainees were all people of color who had been students on a full 23-day Outward Bound wilderness course, had shown their mettle and interest in outdoor work, and had been recruited to join the program to add some diversity to a mostly white staff.

My path to the program began a couple of months before graduating North High School in Denver, when I heard an announcement on the scratchy PA system about a full scholarship for an Outward Bound course. I had been in trouble with the law, dropped out of school twice and never expected to graduate, so just receiving a high school diploma was a monumental accomplishment, and I had no plans whatsoever for what came after that. I’m not completely sure what it was about the announcement that caught my attention, only that I vaguely knew that Outward Bound had something to do with the outdoors, and I had a yearning for the kind of adventures in the wild that I had only read about. Outward Bound offered scholarships to one student in each underserved high school and Boys and Girls Club in Denver, under a program colloquially referred to as “hoods in the woods.” I was one of those hoods.

I had been in trouble with the law, dropped out of school twice and never expected to graduate, so just receiving a high school diploma was a monumental accomplishment.

I ended up being the token scholarship student on an Outward Bound trip with 18 others in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains of southern Colorado. Mountaineering with ice axes, technical rock climbing, crossing miles of sand dunes with a full pack, learning to navigate in the wilderness, and the simple pleasure of self-reliance — of carrying everything I needed to survive on my back — all blew my mind and my horizons wide open. And in that stripped-down version of life, class distinctions faded, and I discovered strengths, skills and leadership abilities I never imagined I had. It very likely saved me from a dead-end life, or worse, in inner-city Denver.

After returning home, I worked whatever manual labor jobs I could find and started buying outdoor gear and talking my friends into backpacking trips and even some risky rock climbing using cheap rope from the hardware store. A year later, I learned about a program at a small community college in Leadville, Colorado, that trained outdoor leaders. I couldn’t imagine anything better and enrolled immediately. I joined the Outward Bound minority training program soon after.

Mark’s story was similar — an uncertain future, some shady activities with friends, a conscious decision that he “didn’t want to die in the city” and an Outward Bound scholarship that required a month’s worth of work in the organization’s gear warehouse. Mark was an artist as well as a gifted athlete. Despite harassment he’d endured as a brown kid playing a white sport, he had become a champion tennis player in high school. He entered marathons spur of the moment, without training, and finished in respectable times. Here is a legendary story about Mark: The capstone of a standard 23-day Outward Bound course at the time was the challenge of a long trail run — sometimes a full 26.2-mile marathon. Sitting around a campfire the night before one of those Outward Bound marathons, students were talking about their reasons for running, saying they liked to push themselves or that it was good for their mental health. With a distant look in his eyes, Mark said, “I run for the colors.” After a moment, someone asked, “You mean the colors of the landscape? The sky?” “No,” he said, as if it were clear as day. “I see colors when I run.” Any visit to Mark’s house brought him to the front door splattered with paint from his latest project. Things others thought were mundane or gross he found beautiful. He saw art everywhere.

That’s Mark — tapped into a liminal dimension that others only glimpse. He had a far more spiritual and inspired approach to outdoor adventure than some of our gearhead colleagues, who seemed most interested in acquiring the latest equipment and checking popular routes and summits off their punch lists. What both of us wanted, by contrast, was to use our gear and skills to escape to those wild places and precipitous edges where we felt most alive. He often talked about the warrior spirit from the Indian part of our Chicano blood and how, when traveling in the wilderness, we stood on the shoulders of centuries of ancestors in the Southwest.

We both had worked a couple of courses as “minority trainee” instructors — a notch below assistants — which gave us more outdoor access and experience, but it paid squat. And we did not always feel welcome. Many instructors could step right into jobs with Outward Bound because they came from privileged backgrounds and had access to outdoor gear and experiences. That was not the case for us, and our training program was intended to correct that. But labeled as minority trainees, we were marginalized and tokenized from the start. We had overheard white instructors talk about what a waste our training program was, making comments like, “If they can’t get the skills and experience and gear they need to be instructors on their own, they have no business here.” As part of one performance evaluation, a blond, blue-eyed senior instructor went so far as to grumble about the incredible free ride I was getting and lecture me about the fact that I still lived in a rough neighborhood and hung with the same sketchy friends I’d grown up with. She probably had her own challenges as a woman in the field and may have thought she was being helpful, but I was dumbfounded when she suggested that I move to Boulder or Aspen to live the proper life of an Outward Bound instructor. Not everyone was like her — plenty of good people and mentors lent a friendly hand along the way — but still, we were often reminded, in both subtle and not-so-subtle ways, that outdoor adventure was an exclusive club, and we didn’t belong.

It is a typical irony that diversity programs tend to assimilate recruits like us into the mainstream, rather than accept and embrace difference. The irony was particularly rich in this case. Outward Bound specifically wanted me to work with disadvantaged minority students because I could relate, but this woman thought I should turn myself into someone those students would have no interest in talking to.

Looking back, I’m shocked at how passive I was in encounters like this — and there were a few. It was a survival mechanism I learned early on as I straddled two different worlds, and I usually didn’t feel the insult until a few days later. We have to pick our battles, Mark once advised. I’m proud to see people of color in the outdoors these days speaking their truth, but it was a different world for my generation.

Our original group of nine trainees all came into the program with basic skills, and the previous year, we had spent a week together honing our technical climbing on the Flatirons near Boulder and in Rocky Mountain National Park. A few months later, we applied for Outward Bound funding that allowed seven of us to travel across Mexico on a successful expedition to climb Pico de Orizaba, the third-highest peak in North America. But group participation was waning. The others had jobs they couldn’t get away from, kids to take care of, or other interests they were pursuing.

Mark and I were the only ones who showed for this trip in the Tetons. Even knowing that some folks looked down on us and that we had to get back to the daily grind and our real jobs right after the trip, we were drawn to be there. The summits called to us.

While organizing gear in a campground at the foot of the peaks with our two full-fledged Outward Bound instructors, we jointly decided that Mark and I would go it alone. We may not have had the technical skills of more experienced climbers, but we knew the basics, we were a good team, and we were certain that we could work through any problem.

Mark and I share the same birthday but, despite what astrology might say, we are radically different characters with divergent attitudes and skill sets. Mark provided the emotional strength, fierce stamina and spirit needed for a challenging climb. I added a practical mechanical aptitude, an intuitive understanding of the physics of climbing and placing safe anchors, and a knack for fixing broken things. I am more willing to take risks than Mark — and more hotheaded. One time, some rich guy Mark knew stiffed us after a long day hauling his furniture, and my temper got the better of me. Mark pulled me away before the situation got out of control, explaining that this man had a black belt in karate. It would not have ended well.

CLIMBING IN GRAND TETON

We were the yin and the yang of a perfectly balanced climbing team — the spiritual and the practical, the inspired and the determined, the considered and the impetuous — and we shared the sheer irrational joy of pushing and punishing our bodies to reach a remote mountaintop.

Those Teton trails are damn steep and ropes and climbing gear heavy, but we headed out into the beautiful, wild mountains feeling the strength and optimism of youth and the anticipation of something unforgettable. By the time we reached the Grand five days later, we were in our synergistic groove, having worked out the kinks summiting Nez Perce and Middle Teton. We camped at a spot called the Lower Saddle for a head start up the mountain, hunkering in our sleeping bags behind stone windbreaks as the wind howled over the treeless, rocky pass.

When we rose before dawn the next morning, the wind had stopped, and the sky was clear — a perfect day. We looked up at the summit, around 2,100 feet above us, then started up the Owen-Spalding Route, which is the easiest route to the top but still requires ropes and anchors for safety. Mark and I were tied in to either ends of our rope, and we began leapfrogging our way up, taking turns leading each pitch while the other remained stationary, ready to put the brakes on the rope in case of a fall. We were feeling sure of ourselves, so we didn’t bother with anchors. This approach was dangerous — the lead climber could fall a long distance and get injured or, worst case, pull the belayer down with him. We considered all this but continued without anchors anyway. Maybe that was lazy or cocky or plain reckless, but we did not want to break the rhythm and the grace of our fluid movement up the mountain. We were in the zone.

Still no anchors. A slip here by either one of us would have taken us both down on the talus.

Our confidence held as we made our way upward without a hitch or a hiccup. The rare thrill of being totally laser-focused in the moment kept us aloft. No questions, no second-guessing. Just moving with instinct and faith and trust in each other, our fates bound by a length of rope. I’ve seldom felt such absolute certainty about anything.

A move called “the belly roll” did give us pause. It involved rolling around a bulge in the rock onto a face with 2,000 feet of sheer exposure that bottomed out onto a rocky talus slope. That was immediately followed by another section called “the crawl” where we wedged the right half of our bodies into an 18-inch-deep horizontal crack and carefully inched along for 40 or 50 feet while our left sides hung in thin air over the cliff.

Still no anchors. A slip here by either one of us would have taken us both down onto the talus.

After a few more pitches, we were on the top, breathing deeply as we looked out at the magnificent range of the Tetons stretching to the north and south. We didn’t think to time ourselves, but the 2,100-foot ascent took two — maybe 2.5 — hours. We reached the summit by around 9:15 a.m.

On the descent back to the Lower Saddle (we did use anchors on the way down for a couple of rappels), we realized that we had not seen another soul on the mountain. Grand Teton is on most climbers’ bucket lists, but by some trick of timing, we had the mountain to ourselves that morning. Rather than spend another night in the backcountry, we had decided on the summit to head to Jackson that night for a beer, so we quickly packed and started the 6-mile march down a steep trail to the parking lot. It was a relentless, pounding descent with heavy packs, but we were brimming with energy from the climb, our bodies resilient and knees and hips pumping like pistons.

I know we were not the first or the fastest or the best, but damn, what a climb. That day shines bright in my memory all these years later, not just because it was such an epic and satisfying ascent, but because it was one of a handful of experiences that propelled me into full-time outdoor work and toward a different life. I felt sure that I had earned my place in that world, despite the naysayers and barriers. That confidence stayed with me as my life unfolded in ways that I could never have imagined in my wildest dreams on that spring day at North High School when I first heard about the hoods-in-the-woods scholarship. After a few years leading outdoor programs, I worked as a national park ranger throughout the Southwest, taught environmental education programs in Yosemite National Park, traveled and adventured around the world, earned a master’s degree in applied cultural anthropology, spent a season doing grad school fieldwork on the Tibetan Plateau, published books about environmental justice, and ended up in leadership positions in the conservation community. Mark led a few more Outward Bound trips then went back to his roots to become a successful tennis coach — taking one high school team to the Montana state championships — and a tennis pro. He created programs to introduce underserved city kids to tennis and is still winning tournaments. Like that day on Grand Teton, life has been an unexpected journey and a hell of a ride for both of us.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Though I still often find that I’m the only brown face in the crowd and occasionally feel like a stowaway who snuck onto the boat when nobody was looking, I am dedicated to protecting the sorts of wild places and public lands that saved me. Those wide horizons broadened my own horizons and opened the door to so many meaningful relationships and opportunities. And they still keep me sane.

I did not get into outdoor adventure or conservation work to be a diversity advocate, but the lack of inclusion in this arena is hard to miss. Those of us in a position to make a difference have a responsibility to challenge the status quo and help provide access to places and experiences that can change lives. Mark and I may have paved the way for others, but the struggle is far from over, and we still have work to do.

But none of that was on my mind that day on Grand Teton. I wasn’t thinking of the past or future, and I wasn’t trying to shatter any glass ceilings — I was just engrossed in the moment. I will always remember in my bones the joy and certainty I felt. That morning, I never doubted that I belonged. Anything was possible.

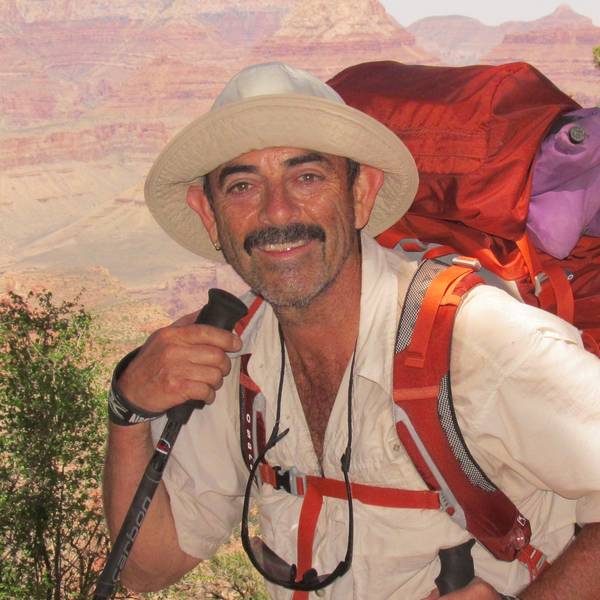

Ernie Atencio lives in his northern New Mexico homeland near Taos and still occasionally climbs a 14,000-foot peak or disappears in the wilderness for days at a time. He was the first person of color to be hired as a regional director at NPCA. A skilled tennis professional, Mark Martinez Luna lives in Denver, where he continues to make award-winning art. The two men remain good friends.

About the author

-

Ernie Atencio Former Southwest Regional Director

Ernie Atencio Former Southwest Regional DirectorErnie Atencio fell in love with parks and wild places at a young age and has spent most of his career working in and for those places.