Spring 2022

Charley Harper’s World

Remembering the late artist — and his vibrant national park art — on the occasion of his 100th birthday.

In 2006, at age 84, artist Charley Harper discussed what he called “minimal realism” in a wide-ranging radio interview. “I work flat, hard-edged and simple,” he told designer Todd Oldham on WVXU, Cincinnati’s NPR station. “Instead of trying to put everything in, I try to leave everything out. And that works pretty well.”

This clear-eyed approach translated into bold, graphic compositions with an unmistakable style. Though his beloved ladybugs and jaunty cardinals may be the best known of his creations, his oeuvre spanned all the natural world. His works — commissioned by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ford Motor Co., Hallmark and many others — were always meticulously designed and relentlessly researched. (He claimed to own more bird guides than anyone in the country.) Exhibited from Los Angeles to Germany, the artworks inspired devotion and today remain as popular as they are ubiquitous.

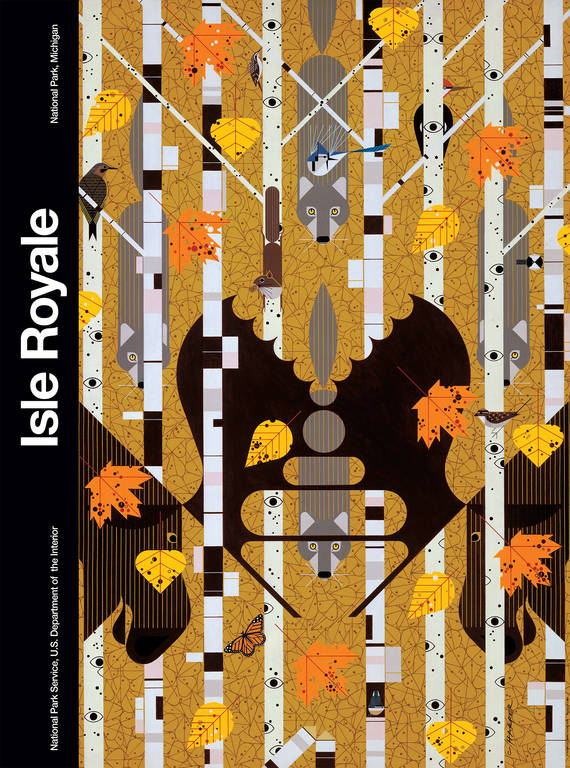

Wolves and moose roam through birch and aspen forests in Harper’s poster of Isle Royale National Park.

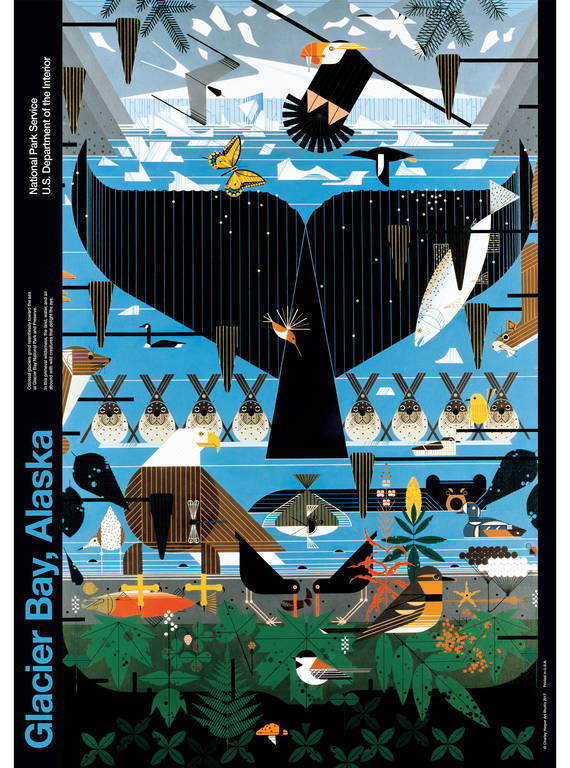

ARTWORK ©CHARLEY HARPER ART STUDIOHarper inserted more than 30 species, including a chorus line of harbor seals, a tufted puffin and a salmon, into his depiction of Glacier Bay.

ARTWORK ©CHARLEY HARPER ART STUDIOSchools of colorful fish, plus coral, mollusks and a sea turtle, give life to Harper’s coral reef, which he called “probably the hardest thing I’ve ever had to paint.”

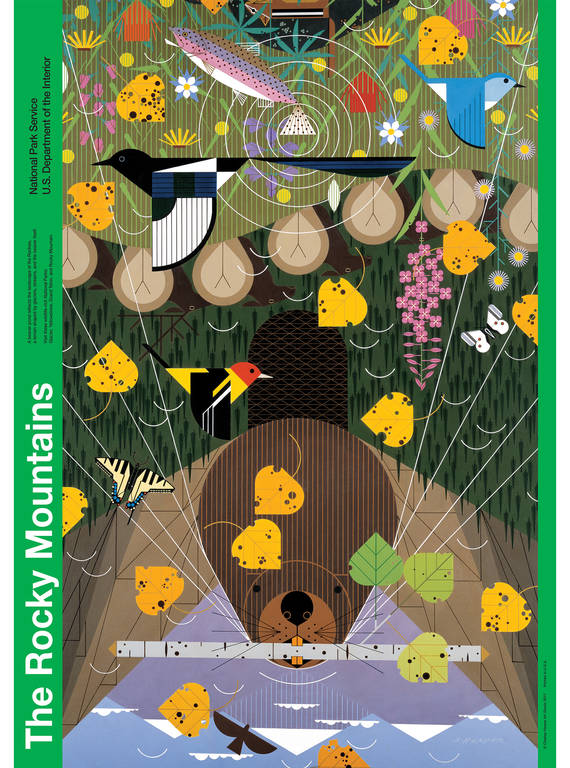

ARTWORK ©CHARLEY HARPER ART STUDIOA montane ecosystem, complete with elk, fireweed and snow-capped peaks, is reflected in a beaver pond in Harper’s poster of the Rocky Mountain national parks.

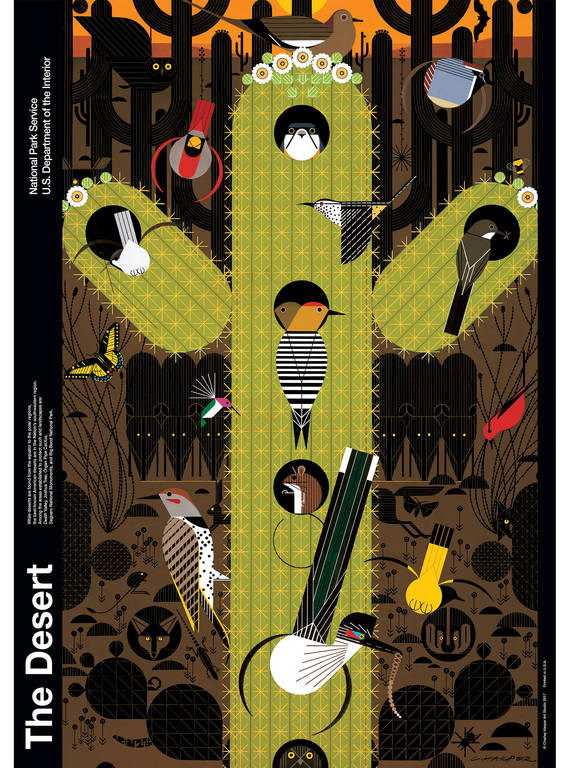

ARTWORK ©CHARLEY HARPER ART STUDIOHarper’s distillation of a desert park shows the yellow eyes and dark silhouettes of javelinas and other critters, as well as the many species of birds that nest in the saguaro cactus.

ARTWORK ©CHARLEY HARPER ART STUDIO“He just had this way of getting you to look at things,” said Mary Yakush, a writer and editor at the National Park Service’s Harpers Ferry Center for Media Services in West Virginia. Hoping to draw attention to Harper’s artistic chops and lasting legacy, Yakush recently curated a virtual exhibition of the 10 national park posters Harper created in the 1970s and 80s, which were commissioned by the center’s then-director, Marc Sagan. The timing of Harper’s commission was key, she said, because people were looking to the relatively new Harpers Ferry Center to define the Park Service’s graphic identity. “And that’s really what Charley Harper did,” Yakush said.

For the assignment, the World War II veteran — accompanied by his wife and two other couples, including Sagan and his wife — crisscrossed the country visiting national parks from Hawai’i Volcanoes to Isle Royale. The resulting paintings, cherished by the Park Service and sold broadly as prints, are complex, vibrant and playful. A beaver, that dominant ecosystem engineer, reigns front-and-center in the poster for the Rocky Mountain parks (encompassing the national parks from Glacier down to Rocky Mountain), and a panoply of briny sea creatures occupy their appropriate tidal zones in the depiction of the Atlantic barrier island parks (including Assateague Island, Cape Hatteras and Fire Island national seashores, among others).

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›“If anything, his works remind me of a tapestry,” Yakush said. Layers of tempera paint and sharp lines form a mesmerizing web of species, often challenging the viewer to find a focal point. Loath to paint a creature out of context, Harper, who graduated from the Art Academy of Cincinnati, took pains to place each species where it would naturally be found, often distilling the workings of an entire ecosystem into a single illustration. He attributed his ability to convey the breadth of a place in one painting to his multi-month honeymoon road trip with his wife and fellow artist, Edie Harper, in 1947. “That’s where I came to grips with the idea of simplifying,” he said in the 2006 interview with Oldham. “You have to simplify Rocky Mountain to get it on a piece of paper.”

The artist’s son, Brett Harper, believes his father, who would have turned 100 this August, would be pleased that his paintings continue to inspire park visitors and remind them of the interconnectedness of the natural world. At heart, “he was an environmentalist,” Brett said, recounting how he found a letter his father penned in 1966, in which he wrote that he would have been a conservationist if he hadn’t been an artist. “In a sense,” Brett said, “he ended up doing both.”

About the author

-

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online Editor

Katherine DeGroff Associate and Online EditorKatherine is the associate editor of National Parks magazine. Before joining NPCA, Katherine monitored easements at land trusts in Virginia and New Mexico, encouraged bear-aware behavior at Grand Teton National Park, and served as a naturalist for a small environmental education organization in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.