80 years ago, the federal government imprisoned innocent civilians for their Japanese ancestry. Today, survivors and their descendants fight to preserve the sites where these injustices took place — and to not let history repeat itself.

The Tule Lake Segregation Center sits near the California-Oregon border on land that is largely bereft of vegetation other than tall grass and sagebrush. The site is flat as a pancake with the exception of Castle Rock, an 800-foot bluff offering views of nearby Mount Shasta. Near the top sits a replica of a cross placed there by some of the people of Japanese descent who were imprisoned below.

It’s a beautiful place to reflect on an ugly period in U.S. history.

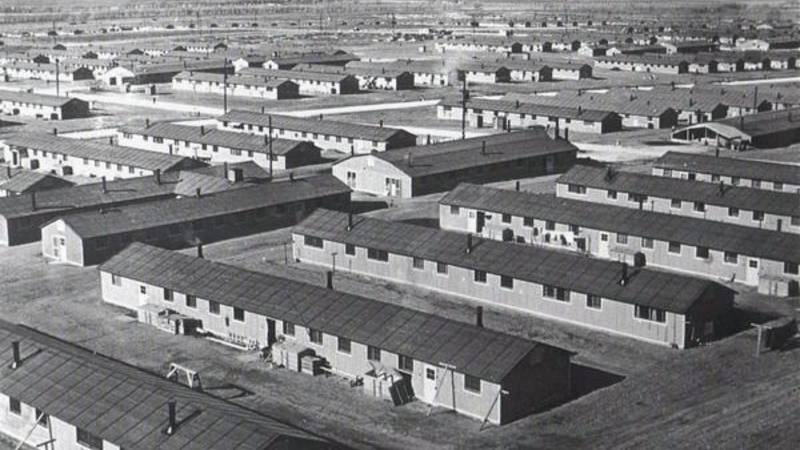

Tule Lake is one of 10 “war relocation centers” where thousands of people who had committed no crimes were imprisoned indefinitely during World War II based solely on their Japanese ancestry.

The Day of Remembrance Marks Need for Continued Japanese American Incarceration Site Protections

Conservation group advocates for further protections to honor survivors and descendants’ experiences.

See more ›That hellish period began when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. The date is marked annually as the Day of Remembrance — this year will the 80th — and each year, fewer people are still alive who bore witness to this experience.

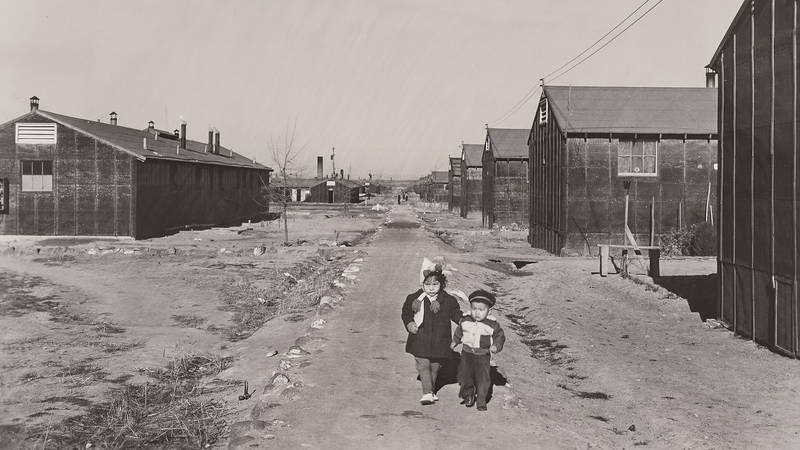

Stan Shikuma once visited the place with his mother, Miki Okano, who’d been imprisoned at Tule Lake during World War II. She was one of some 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry who were incarcerated by the U.S. government at the outset of the war. Shikuma asked his mother if she’d recognized any landmarks along their drive in.

“Why should I?” she replied. She’d arrived with her family on a train with all its shades drawn for security purposes. They’d left on a bus during the dead of night.

Another survivor of Tule Lake, Dr. Satsuki Ina, also didn’t have reference points for her initial return to the concentration camp site. She was born there, in 1944, to parents who’d been relocated from another camp after answering “no” on a government-issued “loyalty” questionnaire.

Detainees were asked whether they would serve in the U.S. military and swear loyalty to the United States, and those who answered “no” to both questions were stigmatized as “No-Nos” and confined to this maximum-security facility. Tule Lake was viewed by some as a place for troublemakers; others, especially now, regard it as a center for protest.

The shame of the experience had haunted Ina’s family until their first visit back, on a family road trip when she was in high school.

“What I was struck by at that time was the silence from my parents,” Ina recalled. “We just kind of looked at it from a distance and then got back in the car and continued our drive.”

Mike Ishii also found significance at Tule Lake, even though he doesn’t have direct lineage to the northern California facility. His family had been incarcerated at Minidoka, in Idaho. After pilgrimages to Tule Lake had transitioned from reunions to efforts to promote healing, education and history, Ishii, a trained facilitator, was recruited to help lead the intergenerational discussions that became the focus of that transition.

The first time he visited the grounds, Ishii’s response was vehement.

“I vomited,” he remembered. “I felt such overwhelming grief. It was like having my insides ripped out.”

Those three reactions to visiting Tule Lake — feelings of dislocation, shamed silence and extreme grief — could also describe stages of forced removal itself for members of the Japanese American community during World War II.

Ina, Ishii and Shikuma used their shared connection to Tule Lake as an inspiration for creating Tsuru for Solidarity, an organization that uses the moral authority of the Japanese American community’s WWII incarceration experience to advocate against immigration bans and detention impacting other communities of color. Tsuru has chapters or affiliates in most major cities in the U.S., as well as in Canada and Japan.

Encapsulated by the hashtag and slogan, “Never Again Is Now,” the urgency of Japanese American activism is fueled by events that feel far too familiar.

Amache Japanese American incarceration site on verge of becoming national park site

Unanimous Senate and House passage puts preservation campaign waged by survivors, descendants and advocates near completion

See more ›Of the 10 War Relocation Authority camps, only Tule Lake, Minidoka and Manzanar in central California, plus a smattering of related sites such as Honouliuli National Historic Site in Hawaii, have federal protection through the National Park Service. A measure to designate Amache, an incarceration camp in Colorado, as a national park site just passed a unanimous Senate vote earlier this week and is close to being approved by Congress. A handful of sites, including Heart Mountain in Wyoming and Topaz in Utah, have private support, and two WRA sites in Arizona — Gila River and Poston — are located on Native American reservations.

Federal protections are crucial because places such as Amache and Tule Lake stand as some of the last authentic remnants of this dark history, and several of these sites are threatened by encroachment.

At Tule Lake, the installation of a 10-foot-high security fence for an adjoining airstrip is viewed by incarceration camp survivors as insensitive at best and, at worst, desecration. The airstrip is located on land where Japanese American families were housed during the war; homesteaders had bulldozed the Tule Lake cemetery and shoveled the dirt and human remains into the grid of ditches upon which the barracks were located.

“The spirit of our community resides in these places,” said Ishii, 56, a New York-based organizer and musician who is a PhD candidate in Chinese medicine. “These are sacred sites for Japanese Americans.”

Shikuma, 68, an activist, organizer and artist who lives in Seattle, said, “If you accept the premise that we can learn from our mistakes and then say that we’re not going to preserve or memorialize any of those errors, mistakes or atrocities, it means that we will never learn from them. That’s a dangerous and scary proposition.”

Many people are working to preserve what is left, and the documentation of this history has progressed, particularly during the past 40 years.

An American Journey

Was the story of Minidoka National Historic Site his story, too?

See more ›The fight for redress, which was granted to 82,250 former detainees in 1990, pushed incarceration camp survivors to fight through cultural norms and lingering trauma to share their experiences. The University of California, Berkeley, has more than half a million objects in its Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement digital archive. UCLA and the Japanese American National Museum each have hundreds of thousands of objects, though only a fraction of them is digitized. Densho, a nonprofit in Seattle, has nearly 111,000 digitized objects, including 1,075 oral histories.

Tom Ikeda, who is retiring from Densho after founding it 26 years ago, says his organization has focused on digitization to improve access to the history. He still believes in the imperative to preserve the incarceration camps and other sites as anchors to the truth.

“I think these physical sites are an important reminder that this happened here — that even in a democracy where everyone is supposed to have equal rights, terrible injustices can happen if we’re not vigilant in standing up for each other,” said Ikeda, whose parents were incarcerated at Minidoka during World War II.

In addition to Tule Lake and the nine other WRA camps, there is a labyrinthine network of some 70 assembly centers, numerous Department of Justice and U.S. Army detention facilities, and assorted additional supplemental holding centers and designated communities.

One of those, the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial near Seattle, is nestled in a clearing among six acres of firs, alders and cherry blossom trees. At its center is a story wall of old-growth cedar, 276 feet long, one foot for each person of Japanese descent who was exiled from Bainbridge, the place where the forced removals began during World War II.

Return to Manzanar

As the number of Japanese-American incarceration camp survivors dwindles, a new generation strives to keep the story alive.

See more ›My first visit there was disconcerting. The tranquility of the place seemed incongruous with its history of hatred. I expressed my confusion to Clarence Moriwaki, a third-generation Japanese American who spearheaded efforts to produce and care for the memorial, now a unit of the Minidoka National Historic Site, managed by the National Park Service.

Moriwaki seemed almost to relish in my reaction. Others, including survivors he’d consulted, had similar hesitations. But there already was too much ugliness and pain associated with the World War II incarceration, he’d replied. The Japanese “less-is-more” aesthetic of the site was a testimony to the survivors, many of whom had been burdened by shame and approached this part of their past according to the Buddhist notion of “Gaman” — enduring the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.

This place was intended to offer a release — and hope.

“We wanted to create the most beautiful and contemplative site possible that would impart to all survivors and their loved ones that our nation respects, cares and honors them,” said Moriwaki, who now is a Bainbridge Island city councilmember. He added that the memorial also is meant to “inspire the hope in peoples’ hearts of our aspirational phrase: ‘Nidoto Nai Yoni — Let It Not Happen Again.’ “

That aspiration now drives the work of Satsuki Ina. At 77, she is a trained psychotherapist whose practice has morphed into helping heal the collective trauma suffered by her community.

Ina was attending Cal Berkeley when she started to understand more fully what she and her family had endured. Her parents had both renounced their U.S. citizenship, and her father was locked in a stockade for other protests. He also had been banished for two years to a detention center outside Bismarck, North Dakota.

The Art of Gaman

Bearing the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.

See more ›While Ina’s parents were objecting to their treatment as “alien enemies” by their own government, other Japanese Americans responded to the accusation of being disloyal with ultra-loyalty. The ultra-loyalists in turn cast the Tule Lake protestors as instigators who prolonged the incarceration experience.

“Our parents transmitted to us that fear that, if you’re not the best student in the class, the hardest working, the most compliant, then terrible things will happen to you,” Ina explained. “That’s kind of the pall that hung over many of us.”

That pall no longer awaits Ina at her birthplace. Every time she returns to Tule Lake — so far, about 20 times — she finds a private spot. There, she lies on the ground, her heart to the earth.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

“It’s feeling the pain and sorrow that was so alive at that time, and has been so suppressed ever since,” Ina explained.

“For me, it’s kind of like putting your ear next to a pregnant mother’s stomach and hearing the heartbeat or the movement of her baby inside. It feels like somehow getting to the heartbeat of what this land witnessed and what it absorbed. And then it mirrors and reflects what I’ve buried and what I’ve absorbed.”

In other words, to heal is to first remember and feel.

Learn more about NPCA’s work to preserve World War II incarceration camps at npca.org/dayofremembrance

About the author

-

Glenn Nelson Contributor

Glenn Nelson ContributorGlenn Nelson founded The Trail Posse (trailposse.com), a nonprofit media project covering the intersection of race and the outdoors, and writes a column about race and equity for SouthSeattleEmerald.com. He is based in Seattle.