Winter 2022

The Land of the Giants

An artist’s view of Sequoia & Kings Canyon national parks in the age of extreme wildfires.

I traveled to Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks in the brief interlude between two devastating wildfires.

In July, more than six months after the Castle Fire of 2020 had been contained, and before the KNP Complex Fire had swallowed thousands of acres, I brought my pencils, pastels and paper to this landscape of extremes nestled into the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada. I wanted to capture this place, this land, these trees — and the recent fire and threat of other blazes lent my project an air of poignancy and urgency.

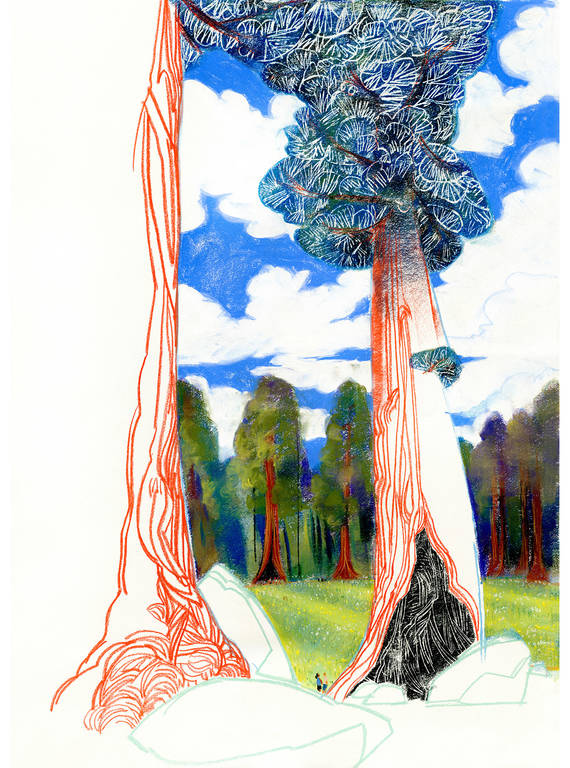

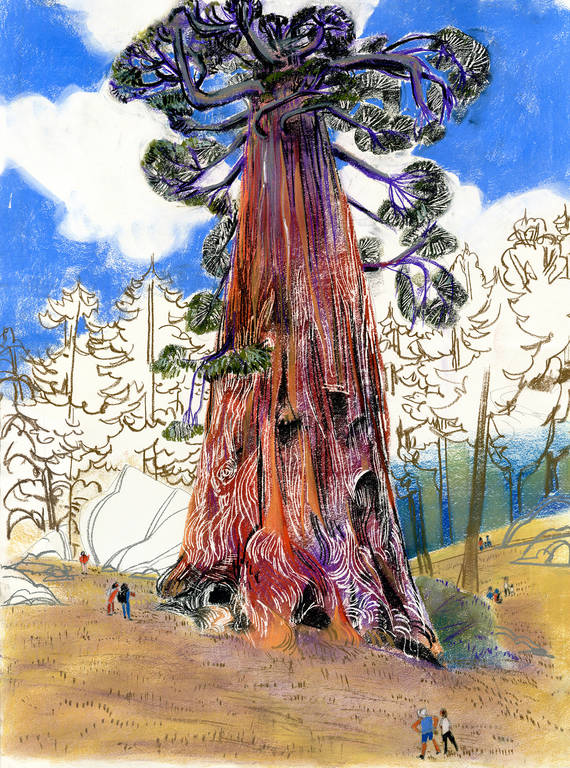

When I arrived in Sequoia, the park looked parched, and the grass was brittle. But as I climbed higher into the park, I felt like I was witnessing a second spring. The understory was lush and green from late snowmelt, with ferns, grasses and wildflowers covering the forest floor. I had visited the park before, but seeing the sequoias in the Giant Forest, where more than 2,000 of them stretch toward the sky, is still shocking; the immensity and age of these ancient trees are almost too much to comprehend. The trees can live for over 3,000 years, and they can grow to more than 300 feet — taller than a 26-story building. With their orange-hued bark, the giant sequoias stand out among the sugar pines, incense cedars, and white and red firs, glowing like candles.

One might expect sequoia cones to be oversized, but they’re smaller than chicken eggs.

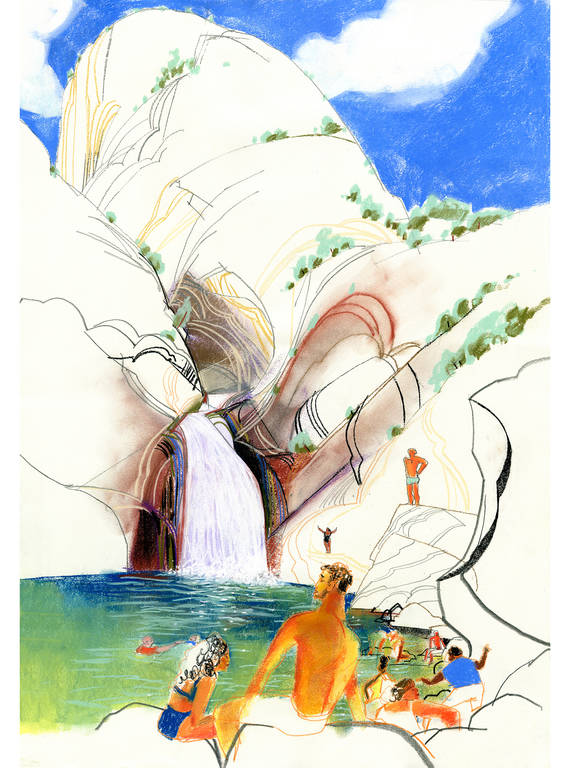

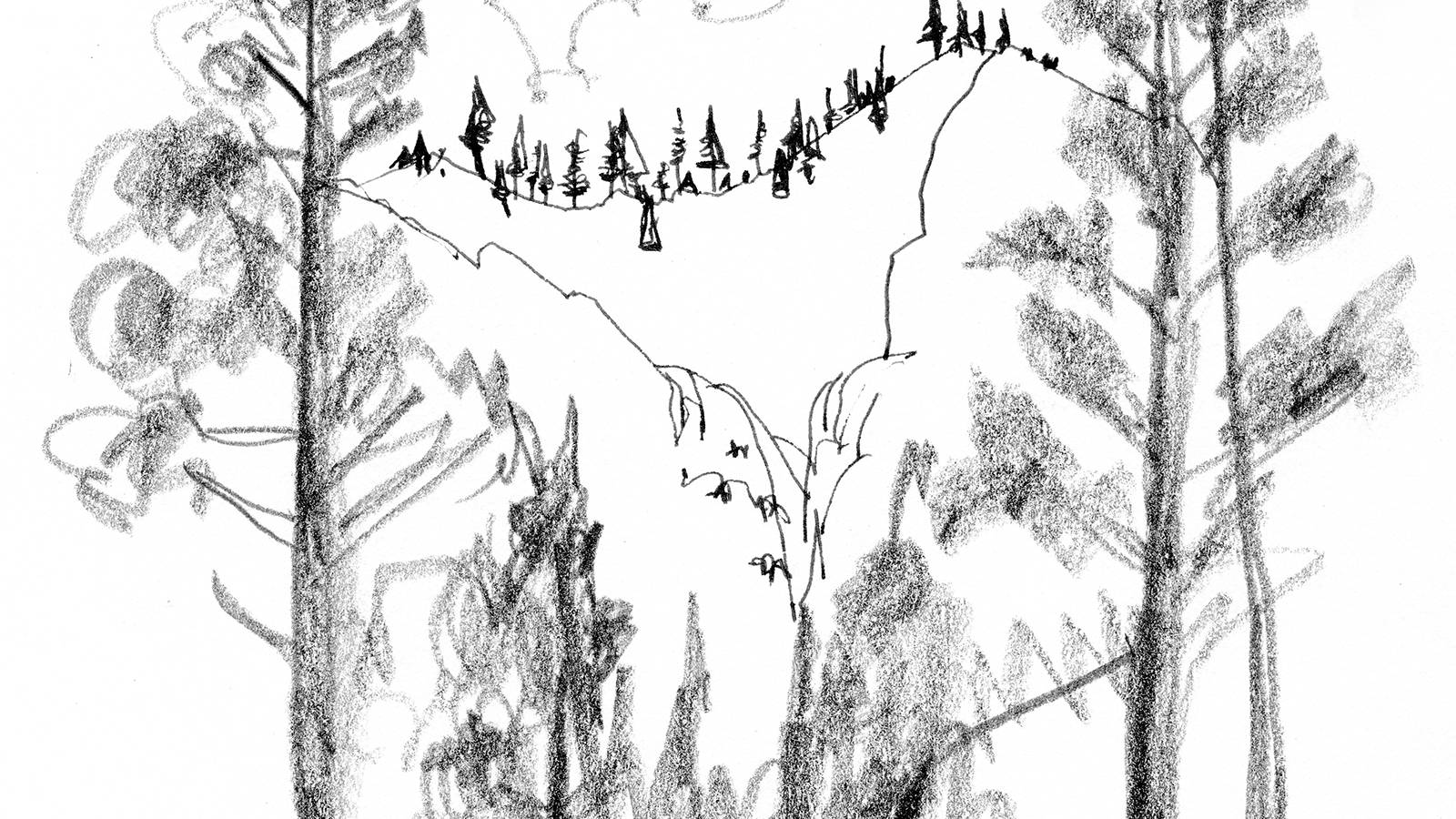

©EVAN TURKJust to the north, at Kings Canyon, I drove high into the mountains and down into the park’s namesake canyon, which was carved by glaciers over millions of years. I touched sequoias, dipped my toes in the icy, turquoise waters of Kings River and listened, mesmerized, as Roaring River Falls coursed through a rocky tunnel and crashed into the sparkling pool below. For two nights, I camped in the park, watching from my campsite as stars and thunderclouds passed over the treetops and the canyon’s granite walls.

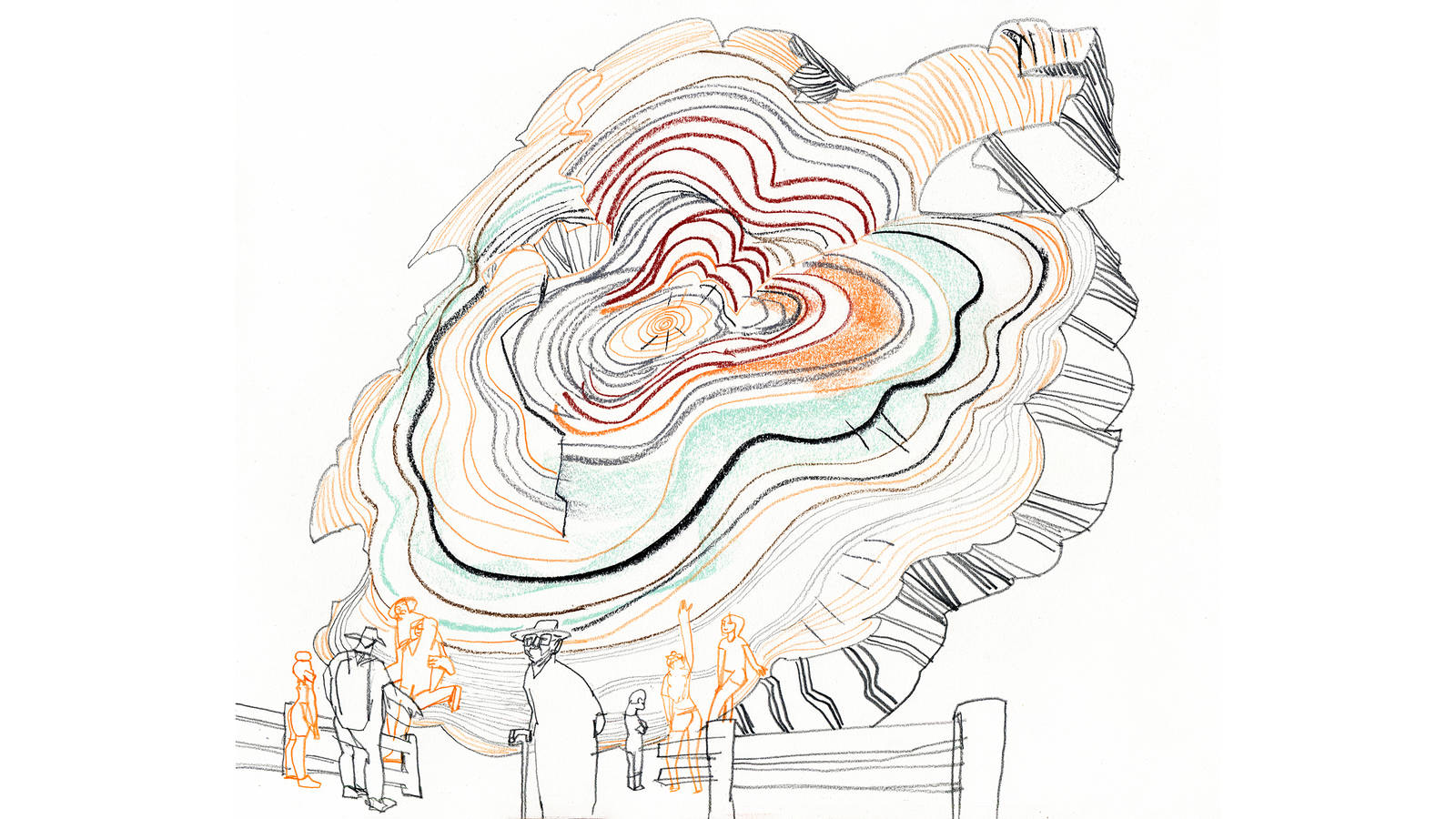

Giant sequoias are exquisitely designed to live alongside wildfire. The heat of forest fires causes the small cones to release even smaller seeds, and mature trees are protected by spongey bark, which can be more than 18 inches thick at the base of the trunk. In addition, fires typically engulf the understory, burning away competition and leaving behind soil that is hospitable to seedlings.

But these are not typical times. The climate crisis has led to increasingly severe droughts and more extreme, untamable wildfires. It has become much more difficult for mature trees to withstand the blazes tearing through the West. Last year, the Castle Fire destroyed at least 10% — and possibly as much as 14% — of the giant sequoias in the Sierra Nevada. As I write this, the wildfire in and around Sequoia and Kings Canyon continues to burn, and the toll won’t be known for months.

Sometimes I feel helpless, but the trees themselves offer a glimmer of hope. Many bear the scars of centuries of previous fires with pitch-black, sometimes oozing, wounds in their mighty trunks. But the trees persevere, and over the years, the bark often grows over the old wounds like scar tissue. Standing in the shadows of these ancient behemoths, I start to see time on their scale and can’t help but feel we will make it through to the other side.

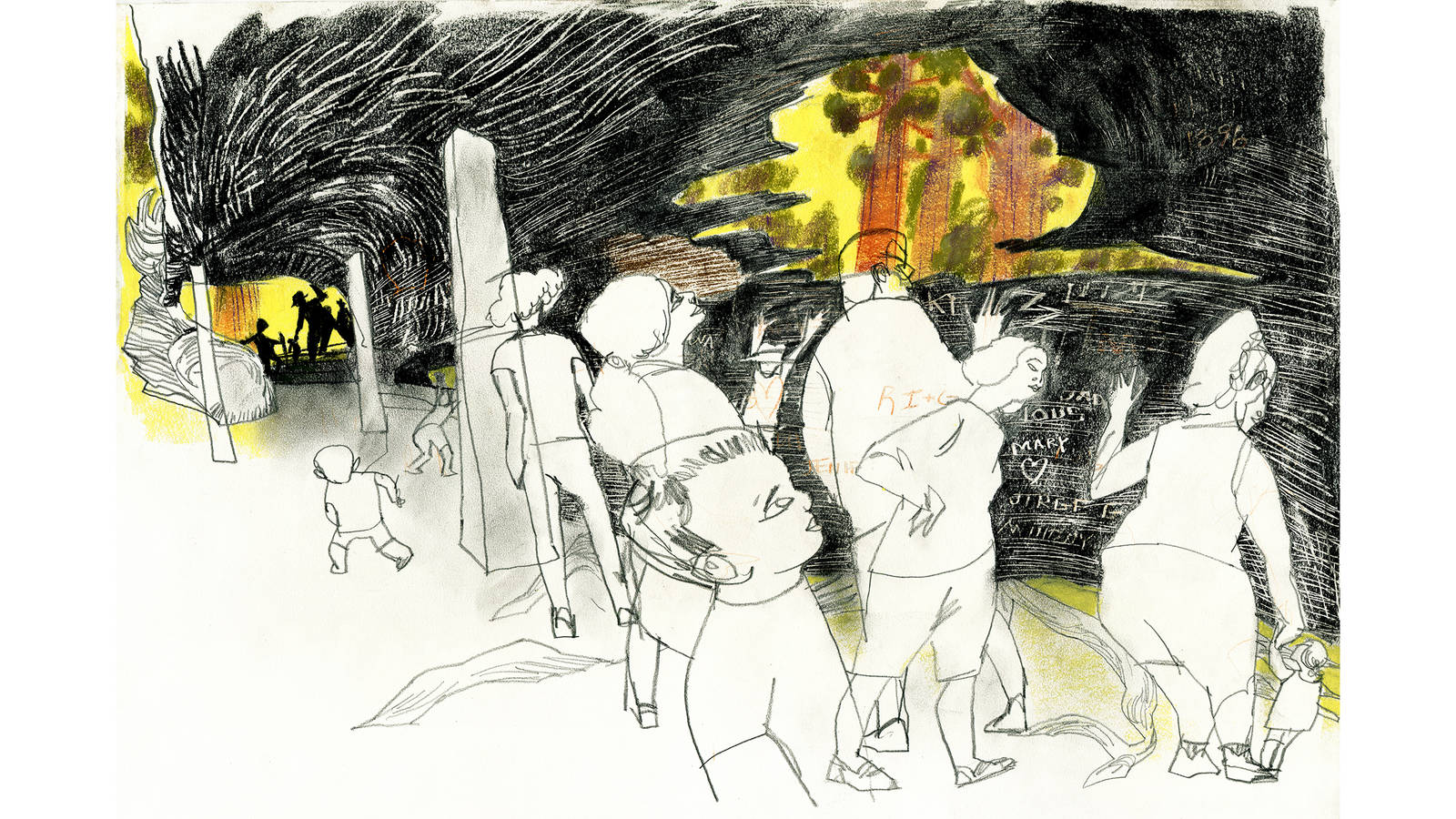

Fallen Monarch in Kings Canyon served as a refuge in the parks’ early years. Employees camped inside, and cavalry kept their horses there. The felled tree also once allegedly served as a saloon. Park staff believe that Native Americans used downed sequoias like Fallen Monarch as shelter. Indigenous people — including the Mono (Monache), Yokuts, Owens Valley Paiute-Shoshone, Western Shoshone and Tübatulabal — lived in the region for thousands of years before they were forcibly removed to make way for the park.

©EVAN TURKSequoia and Kings Canyon national parks cover nearly 900,000 acres of land in California’s southern Sierra Nevada mountains. The closest airports are Fresno Yosemite International Airport and Visalia Municipal Airport, but several other airports can be reached by car within a few hours.

©EVAN TURK

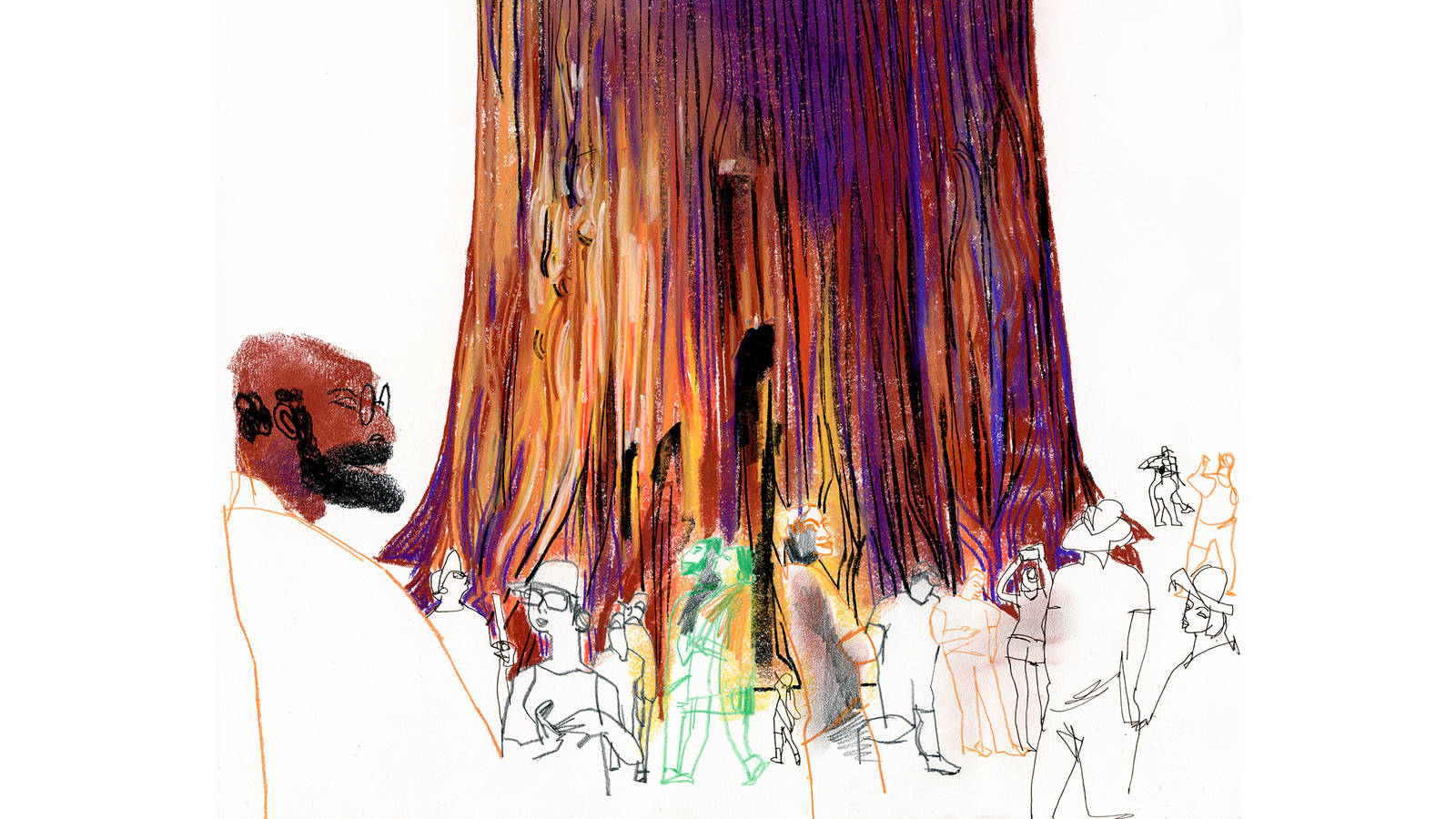

General Sherman Tree stands apart, but it is often ringed by throngs of tourists from around the world struggling to fit their companions and this living monument into a single photo. Scientists estimate that the tree is at least 2,000 years old, and possibly much older.

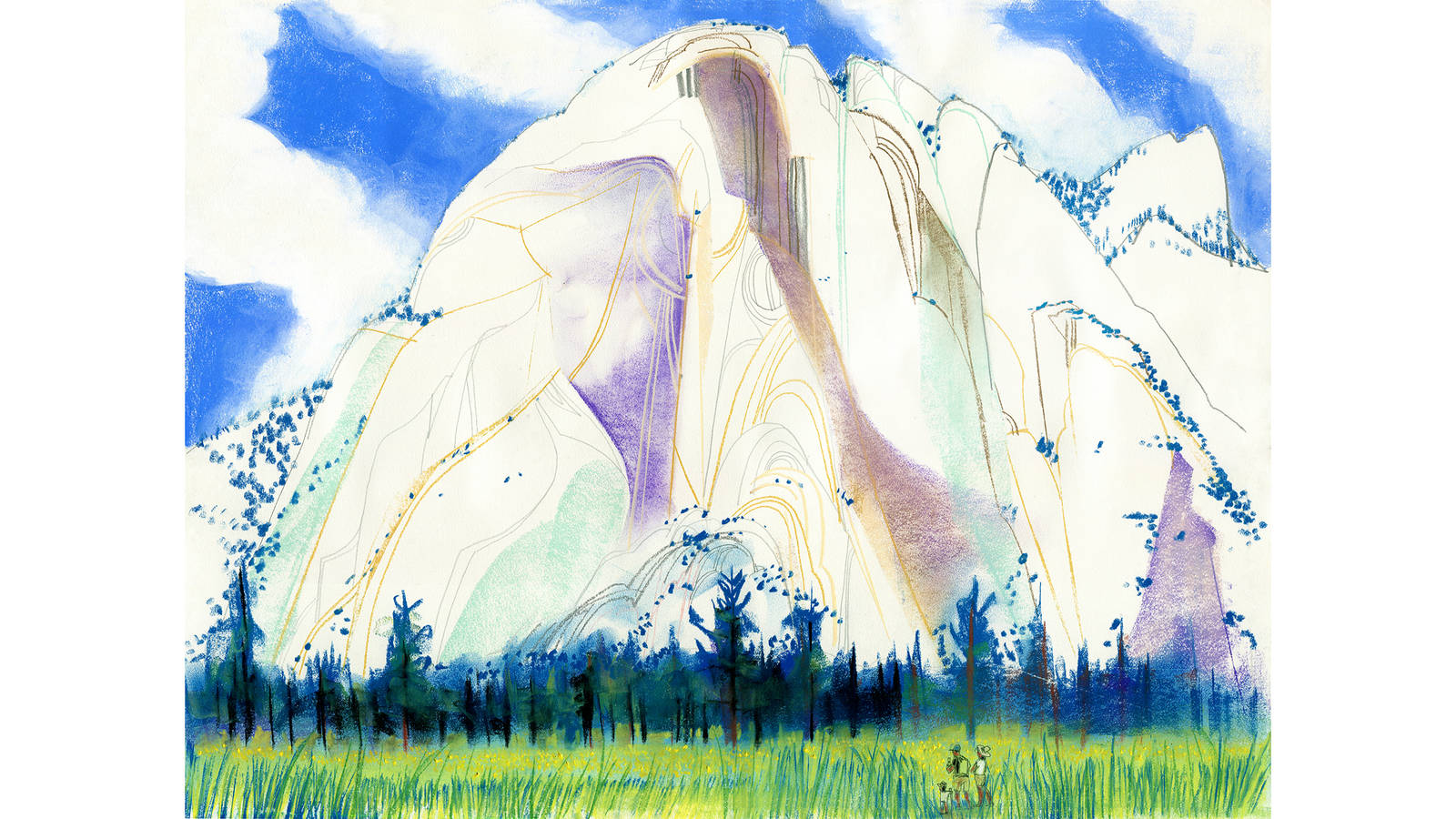

©EVAN TURKThe lush Zumwalt Meadow in Kings Canyon National Park is surrounded by immense granite walls.

©EVAN TURKI took a quick plunge into the frigid pool below Roaring River Falls in Kings Canyon, before making this drawing while drying off on the rocks.

©EVAN TURKThe view from my campsite in Kings Canyon. The Moraine Campground, near Cedar Grove, is roughly an hour away from any cell reception or Wi-Fi.

©EVAN TURKA sudden commotion caught my attention as I ate dinner by Kings River, and I turned to see a black bear and her cub saunter by. As onlookers shouted, the bears scampered back to safety across the river, the little cub leaping and stumbling across the slippery rocks behind its mother.

©EVAN TURKAt King’s River I was greeted by squawks and chirps of Steller’s jays (pictured) and woodpeckers.

©EVAN TURKWoodpeckers.

©EVAN TURKGiant sequoias hem in Round Meadow, which is verdant and overflowing with wildflowers even during Sequoia’s dry season.

©EVAN TURKGenerations of humans, animals and plants have come and gone, and the giant sequoias live on, witnessing it all.

©EVAN TURKIn the higher elevations of Sequoia, I saw scores of butterflies and bees flitting through meadows of lupine (pictured), prairie fire and rudbeckia.

©EVAN TURKRudbeckia.

©EVAN TURKGeneral Sherman Tree is the largest tree in the world by volume.

©EVAN TURKAn enormous cross section of a felled tree in Sequoia.

©EVAN TURKChipmunks were everywhere in Kings Canyon.

©EVAN TURKA sequoia continues to grow even after a fire gouged and charred its trunk.

©EVAN TURKI traveled to Sequoia several years ago when I was working on the children’s picture book, “You Are Home: An Ode to the National Parks,” and made this pastel painting.

©EVAN TURKA young sequoia. It is mind-bending to think this little tree could still be around in 3,000 years.

©EVAN TURK

NPCA at Work

Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks hold the dubious distinction of having some of the worst air quality in the park system, thanks to nearby agricultural and industrial activities, as well as vehicle emissions. NPCA and its allies have been working for years to improve the air here, but even small victories take time, and unfortunately, the recent spate of wildfires has exacerbated the problem. This fall, the KNP Complex fire consumed nearly 90,000 acres of Sequoia and Kings Canyon within a month. Not only did the lightning-sparked blaze force community evacuations, demand the efforts of more than 2,000 firefighting personnel and close the parks, the fire belched tons of smoke, ash and other particulates into the air while simultaneously destroying the trees that act as carbon sinks. “Most of the progress that’s been made to reduce man-made sources of pollution locally has been completely wiped out,” said Mark Rose, NPCA’s Sierra Nevada program manager. “It’s devastating.”

Scientists estimate that between 7,500 and 10,600 mature sequoias died in the 2020 fire.

©EVAN TURKEven species evolutionarily designed to live with wildfire, such as the giant sequoias, aren’t equipped to survive them in the age of climate change, Rose said: “It’s just that fire has never behaved like this. It’s never been so hot; it’s never spread so fast.”

To address this new reality, NPCA has been active on several fronts: working to limit greenhouse gas emissions to combat climate change and pushing for more Park Service funding to help parks prevent future megafires, through vegetative thinning and prescribed burns.

Program staff have collaborated with partners to close power plants, halt rampant oil and gas leasing on public land, and hold accountable the agencies responsible for protecting our air, such as the Environmental Protection Agency.

In January 2021, NPCA celebrated a long-sought decision by the California Air Resources Board to end agricultural burning in the San Joaquin Valley by 2025. And by the time the Winter issue hits homes, there may be more good news. As of November, the Biden administration and the state of California were getting close to unveiling ambitious new fuel efficiency standards, and a lawsuit NPCA and co-plaintiffs brought against the Bureau of Land Management was nearing resolution. An agreement could eventually result in a ban on new federal fracking leases on 1 million acres near Sequoia and Kings Canyon.

Tackling air pollution benefits not only park ecosystems, staff and visitors but also all those who live and work in nearby communities. Learn more at npca.org/regionalhaze. -Katherine DeGroff

About the author

-

Evan Turk Contributor

Evan Turk ContributorEvan is an award-winning illustrator, author and animator, who lives in Riverside, California, with his husband and two cats. His work has been featured in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Post, the Chicago Tribune and NPR. His recently published children’s books include “The People’s Painter,” “A Thousand Glass Flowers” and “You Are Home: An Ode to the National Parks.”