Fall 2021

Protecting the Homeland

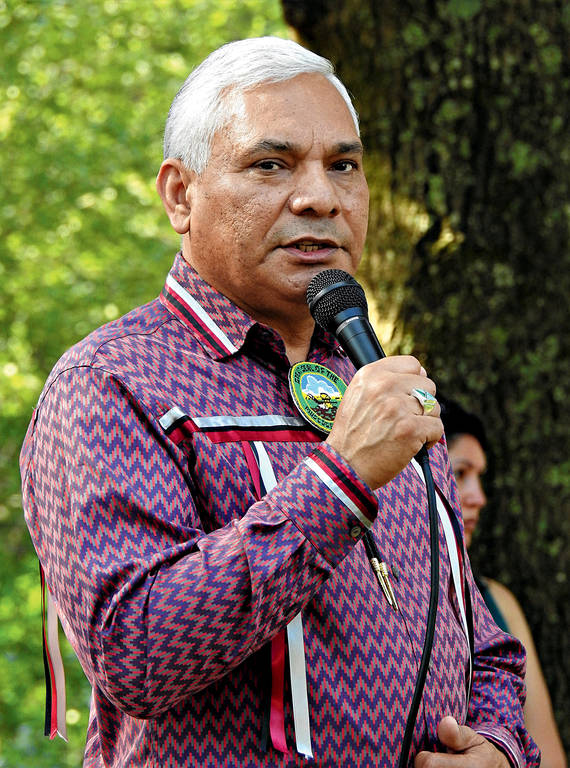

Former Principal Chief James Floyd of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation speaks about his connection to Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park and the need to further preserve the site.

When James R. Floyd, then chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, first visited Ocmulgee Mounds in central Georgia, the ancestral homeland of his people, his experience was “almost overwhelming,” he said.

“The skies, the land, the river, the mountains,” he said of his visit in 2016. “It was like going to a place and feeling it was meant for me.”

James. R. Floyd speaks at the 2017 Ocmulgee Indian Celebration.

©MARK ABBOTT, MUSCOGEE (CREEK) NATIONOcmulgee National Monument was established in 1936, and the site was upgraded to national historical park status in 2019 — thanks in large part to Floyd’s advocacy. The land contains earth mounds as high as 55 feet. Some mounds served as tombs, while others were used to support buildings or perform ceremonies. They were built by the people archaeologists call Mississippians, who lived there more than 1,000 years ago. The area was home to many different American Indian cultures during the last 17,000 years and is considered the cradle of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. Thousands of people come to the park annually for the Ocmulgee Indian Celebration, one of the largest Native American gatherings in the Southeast.

The John D. Dingell, Jr. Conservation, Management, and Recreation Act of 2019, which passed after three unsuccessful iterations of the bill, redesignated the site as a national historical park and quadrupled its size to 3,000 acres; it also authorized a study of a 50-mile section of the Ocmulgee River between Macon and Hawkinsville, Georgia, a corridor that includes undeveloped hills, wetlands and 85,000 acres of contiguous bottomland hardwood swamp. That stretch provides habitat to more than 200 species of birds and 50 species of mammals, including central Georgia’s isolated black bear population. The findings of this study, which will continue until the fall of 2022, could pave the way for an even larger park.

Floyd served as principal chief of the Muscogee (Creek) Nation — a self-governed Native American tribe located in Okmulgee, Oklahoma, and one of the largest federally recognized tribes in the United States — from 2016 to 2020. Previously, he managed the first tribal-owned hospital in the country and worked for a decade at the Portland Area Indian Health Service in Oregon before working in an executive role at the Department of Veterans Affairs. Here, he talks with Melanie D.G. Kaplan about protecting Ocmulgee Mounds, finding peace on ancestral lands and fitting together the puzzle pieces of Muscogee history.

When was the first time you visited your ancestors’ lands?

Floyd (right) stands near the entrance of Earth Lodge with his son Jacob (left) and his wife, Carol.

COURTESY OF JAMES R. FLOYDMy wife and I went with our parents around 1980 and visited some sites in Florida and Alabama. Muscogee (Creek) people have always been in the Southeast. We engaged with the Spanish, French and English, trading furs, metals and small animals for arms and ammunition. Today, you see the absence of our influence and our culture back there. What happened to the Creek people who disappeared? They didn’t disappear. They were forced out [through a series of coerced and brutal relocations to the west by the U.S. government in the 1800s]. The mission now is to communicate that we are not extinct.

What do you remember about your first trip to Ocmulgee Mounds?

It wasn’t until I was elected as principal chief — when I felt a strong obligation to preserve and protect — that I took the opportunity to go. I learned about the bill to expand the park that hadn’t passed in several sessions of Congress, and it was something I felt drawn to. In 2016, my family was there along with other members of the tribe and employees of the Muscogee Nation. The spirits that exist there from ancient times were so powerful to me, and there was a strong sense of peace and belonging — like you needed no introduction.

Tell us more about that feeling, that sense of peace.

Growing up here in Oklahoma, this was home. But where did we come from? It’s like puzzle pieces. You read about these different significant places in the East — Ocmulgee Mounds, Okefenokee Swamp, Trail of Tears, Fort Benning, Horseshoe Bend in Alabama — and you begin to feel the connection. You feel a sense of peace and attachment that’s immediate. We need to put the pieces into place as best we can to form a picture so others can see it as well. When our people are there, they get overwhelmed, knowing their ancestors either traveled those routes or lived in those areas.

When you were principal chief, what role did you play in the expansion of the park?

I took trips to D.C. and tried to keep this in front of congressional members. I coordinated visits from folks at NPCA and in the Georgia area. The tribe would send chartered buses from Oklahoma, and both youth and elders would go down and have ceremonies and set up interactive displays for the public, like bow-making and ancient dugout canoes. In 2019, we had the opportunity to purchase and preserve land in the area known as Brown’s Mount, which lies in the historic Ocmulgee River corridor where our ancestors lived. [The land was threatened by development, and the purchase was the first reacquisition by the Muscogee of land in their historic homeland in Georgia since the time of Indian Removal in the 1830s.] It’s invaluable to the Muscogee people as evidence of the lifestyle of our ancestral people.

Your ancestors lived in Georgia, but you grew up in Oklahoma. What was your family’s connection to the land where you were raised?

When I was young, my parents moved back to their hometown in McIntosh County, Oklahoma, and we lived in Eufaula, a very rural area. There was an Army Corps of Engineers project in the ‘60s to build the largest manmade lake in the state within the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and it uprooted many Muscogee people from their allotted lands. It erased historic towns and relocated many burial sites. My third great-grandparents established Fishertown in 1847, and it survived the Civil War, but all traces of its existence were covered over by the lake. I have mixed feelings about it. The lake is important for flood control and tourism, but the town was part of the Creek Nation, and it’s not there anymore. I always wondered, Were our people in favor of this? Opposed to it? Did they have a voice?

How much did you learn about your ancestors as a child?

What’s Next for Ocmulgee?

Growing up, I was inquisitive, and that stayed with me into adulthood. My dad is Creek, and my mom is Creek and Cherokee. I have eight siblings, and my mom taught us about our family history. My mom still volunteers in the school system, helping kids learn to read. She’s 93.

Had you ever run for anything before you ran for the office of principal chief of the Muscogee Nation?

I had not. I’m not a politician. My family was basically my campaign team, and we funded our own campaign. For us, it wasn’t about money. It was about doing the right thing. My whole career has been in public service. Part of my platform was to protect and preserve our past, and this land in Georgia is an important part of our history that I’d hate to see disappear. It’s a passion we have as a family now. As I get older, this weighs on me. We need to preserve these places because they strengthen our people and give them an anchor — knowing this is where we used to be.

You’ve served on the NPCA Board of Trustees since April 2020. What drew you to NPCA and what do you hope to achieve on the board?

I was drawn to NPCA for several reasons, most importantly because of its mission to preserve, protect and expand land in and around national parks throughout the country. I also saw, as a Native American, that I could bring a voice of Native people and their histories into the national parks that are in Indian Country — Ocmulgee Mounds being an outstanding example. I hope my role on the board will also serve to enhance collaboration and participation of tribal governments in the management of national parks.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland is the first Native American to serve as Cabinet secretary. What are the challenges and opportunities she faces in advancing Native American priorities?

In her role, Secretary Haaland has the opportunity to establish policies that reflect the needs of Native people. She faces immense challenges, such as the ability to balance national parks and oil and gas drilling. We hope we can work with her so she can understand the benefits of the park’s proposed expansion to tribal members.

How different is the Native American approach to land?

I believe it is different. For us, the land is more spiritual. The mounds are evidence of our religious ceremonies. The Ocmulgee River basin is being preserved in a way that multiple groups can come into the area and enjoy it. Tourists can come in and fish or hike, and tribal members can visit their ancestral land. I imagine the public learning more about the Muscogee (Creek) people and understanding that we may have left that area, but we didn’t voluntarily leave, and we’ll continue to be involved. There are a lot of disparate interests in this land, and at this time, I’m fine with that.

This Q&A has been edited for brevity and clarity.

About the author

-

Melanie D.G. Kaplan Author

Melanie D.G. Kaplan AuthorMelanie D.G. Kaplan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer. Her book, "LAB DOG: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research," will be published by Hachette in 2025.