We have a new opportunity to preserve the little-known stories of Los Angeles’ Black founders

Earlier today, the House of Representatives passed the Protecting Our Wilderness and Public Lands Act (H.R. 803). The bill protects over 1 million acres of natural and cultural treasures throughout the country, including lands near Grand Canyon, Mesa Verde and Olympic National Parks, among many other places. One provision in the bill would help preserve some of the last wild spaces in Southern California, as well as the little-known story of Los Angeles’ founders.

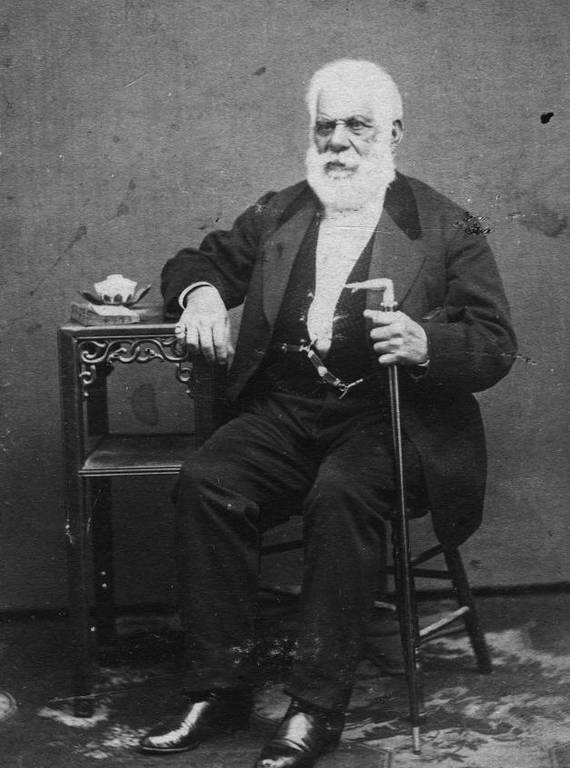

Don Pío de Jesús Pico, the last governor of California under Spanish rule, circa 1890.

Photographer unknownThe City of Angels is usually associated with Hollywood and the entertainment industry, and most people are aware of the region’s Spanish heritage. Less known are the region’s original inhabitants, the Chumash and Tongva people; and even less familiar are the families that founded the city’s historic district, El Pueblo de Nuestra Señora la Reina de los Ángeles, now known as El Pueblo de Los Angeles. These pioneers were a culturally mixed group whose small settlement of 44 people would grow into the nation’s second-largest metropolis of more than 10 million residents.

After Spanish church leaders established the nearby San Gabriel Mission in 1776, colonial authorities were interested in creating a pueblo, or town, that could serve as a center of administration, commerce and agriculture. But recruiting pobladores, or townspeople, for a new pueblo in a remote area, far from Spain’s established colonies to the south, proved a difficult task.

Eventually, volunteers were recruited from as far away as the Sinaloa region in northern Mexico, and 11 families (11 men, 11 women and 22 children) would become the first residents of Los Angeles. According to a 1781 census, the pobladores were a mix of Spanish American castes, including Spaniards, Native Americans and “mestizo,” a Latin American term for people of both Spanish and Native American heritage. But the census identified the largest percentage of settlers, 10 of the 22 adults, as either “Negro” (Blacks of full African ancestry) or “mulatto” (of mixed Spanish and Black heritage), likely descendants of the 200,000 African slaves forcibly brought to New Spain, later known as Mexico, during the Atlantic Slave Trade. Using Native American labor, the pobladores would develop critical infrastructure and agriculture. Many would go on to become owners of large estates, granted to them by the crown, and government and civic leaders.

The founding of the city was far from the only contribution colonists of African descent made to early Los Angeles. Pio Pico, who was of African, Native American and Spanish heritage, served as the last governor of California under Spanish rule, and commissioned the construction of the Pico House. Completed in 1870, the luxury hotel served visitors and new residents of the bustling pueblo, which by then had grown to a population of nearly 6,000. Regrettably, these and other accomplishments would be buried for decades by a city establishment that wanted to distance itself from its Black roots. This was finally corrected in 1981, when a large plaque recognizing the pobladores and their true ethnic heritage was erected to commemorate the city’s 200th birthday.

A colorful shop on Overa Street at El Pueblo de Los Angeles.

© Tom GamacheToday, El Pueblo de Los Angeles is a City and State Historical Landmark. The 44-acre site features a vibrant and bustling plaza with museums, historic buildings and educational plaques that speak to the district’s long history, including the Pico House as well as other notable structures such as the Ávila Adobe, the oldest home in the city. More than 2 million people visit the site annually to see this history, as well as art exhibits, restaurants and a colorful marketplace with vendors selling traditional Mexican fare, among many other items.

El Pueblo do Los Angeles is just one of the historic sites that NPCA has been advocating for years that the National Park Service include as part of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area. We have long supported an expansion effort known as the Rim of the Valley, a 190,000-acre corridor with numerous historic structures, wildlife corridors and irreplaceable green spaces. The legislation that just passed the House today brings this expansion — and the story of these pioneering pobladores — one step closer to being an official part of this beloved national park site.

Stay On Top of News

Our email newsletter shares the latest on parks.

The legislation must now pass the Senate, and I and other NPCA staff and allies will continue to advocate for the area’s national significance and work to see the bill become law. The Rim of the Valley expansion will not just preserve these important places, it will also create opportunities for the National Park Service to partner with local authorities to protect and restore wildlife habitat and cultural resources, enhance visitor and interpretation programs, engage local schools and communities, and share the area’s rich history with a national audience.

My millions of neighbors deserve to know the full history of our city and honor the 44 people who helped create this place we call home.

More places the Rim of the Valley would protect

The Rim of the Valley Corridor expansion of the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area would add over 190,000 acres to the park, help protect critical habitat for wildlife, and expand outdoor recreational opportunities for the region’s 17 million residents. Dotting the corridor are numerous historic treasures that help capture Los Angeles’ history and convey its rich cultural heritage. Including these sites in the park would create opportunities for the National Park Service to partner with local communities to support preservation efforts, expand visitor and interpretive programs, and ensure these stories are told to national audience.

El Pueblo de Los Angeles is the City’s historic core. The bill would also protect Santa Susana State Historic Park, an important trade route for the native Tongva, Chumash and Tataviam people, where village sites remain. Later, a critical wagon trail for early European settlers cut through the area and is still visible in the park today.

Pico Oil Well #4 was established at the start of the region’s oil boom in the 1870s and decommissioned in 1990, when the site was acquired by the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy. The area became the first commercially viable oil field west of the Mississippi, and several structures of the town of Mentryville, which grew to support the oil boom, still stand today.

The Rim of the Valley also contains NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which has been at the forefront of space exploration, the Arroyo Seco, Los Angeles’ first modern freeway, and numerous other sites: a testament to the many diverse peoples and places that have contributed to the story of Los Angeles.

About the author

-

Dennis Arguelles Southern California Director, Pacific

Dennis Arguelles Southern California Director, PacificDennis, Los Angeles Program Manager, works on park protection and expansion efforts as well as engaging diverse and underserved communities not traditionally connected to the national parks.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Pacific

-

Issues