Winter 2021

Hidden Names, Hidden Stories

A journey to the depths of Mammoth Cave to record signatures left by Civil War soldiers.

I stood 200 feet below the Kentucky countryside, looking at three lines of graffiti written in pencil on the white limestone wall of Mammoth Cave. “A Rust 1861, W Garnett, V Hobartt 5th A G 1861,” read the faint cursive. Today, such casual vandalism within the boundaries of a national park would probably get you arrested, but the Park Service considers these Civil War-era signatures and hundreds of other messages in the winding El Ghor passage an important part of the cave’s historical record.

Beside me, Marion O. Smith carefully copied the inscriptions into a small journal as photographer Kristen Bobo fired her flash at an oblique angle to reveal hidden details. As Smith wrote, he placed question marks next to letters or symbols that were hard to make out definitively. These names had likely been left by Confederate soldiers during the opening months of the Civil War, said Smith, who with his dark, rough clothing and close-cropped white beard might have passed as a Confederate ghost himself.

This cave trip on a spring day in 2018 was part of a three-year study of Civil War signatures in Mammoth Cave National Park by Smith, Bobo and Joseph Douglas, a professor of history at Volunteer State Community College. (The next year, the park commissioned a multi-year study by Douglas and Smith to document historical signatures left in Mammoth Cave from the 1810s to the 1930s.) Smith and his colleagues spent long days scouring the walls and ceilings of the cave for signatures, then immersed themselves in archives for scraps of information about the men who etched their names in the rock more than 150 years ago. “These names are little stories you squeeze out of the wall,” Smith said. “Each one is a puzzle, and I enjoy solving puzzles.”

Recording Civil War names can be difficult: Some signatures are layered atop one another, while others are frustratingly succinct, such as “William,” “Capt. Jones,” and “1863.” Names have been smoked onto ceilings by candle flame, scratched into walls with rocks or knives, or neatly handwritten with pencil or ink.

The three-year study, which ended in 2019, yielded only 41 confirmed signatures left by Civil War soldiers during wartime. (Douglas estimates that more than 10,000 signatures were left in the cave over the past two centuries — not to mention pictographs and other markings made by Native Americans.) Such finds add little to the overall record of use of the cave by the Confederate and the Union armies, but by matching signatures found deep underground with photographs, letters and journal entries, the team achieved something they consider equally valuable: They humanized the soldiers who, for a brief moment, took in the wonders of Mammoth Cave as any tourist would — and escaped the horrors of war they would soon revisit.

“There is a poignant aspect to the research,” Douglas said, noting that several of the soldiers who left their mark during a rare day of recreation would later die in battle.

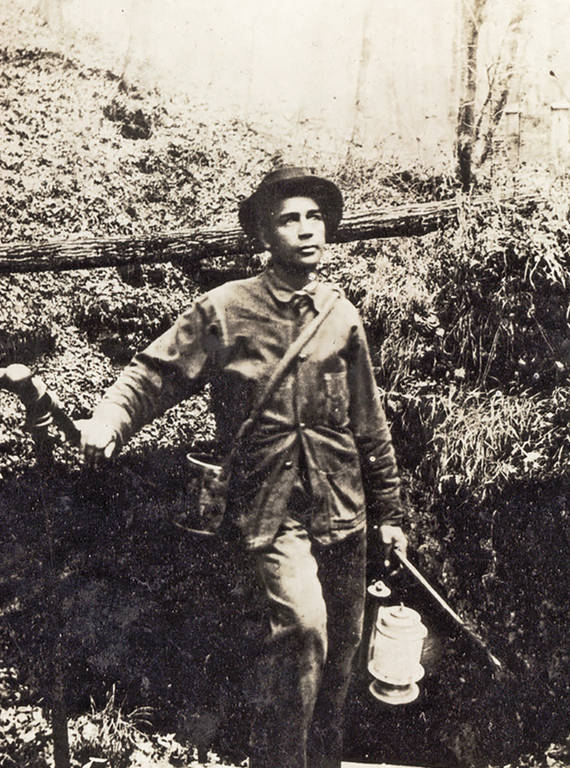

The work is personal for Smith. One of America’s greatest living cave explorers — a description that Smith would object to out of modesty — he is also a trained historian specializing in the Civil War era, and the project gave him a rare opportunity to combine lifelong obsessions. But time is running out. Caving is a strenuous activity, and a recent injury forced Smith to slow down substantially. At 78, he wants to make a lasting contribution to the history of the cave before no longer being able to do so.

I had asked to join the trip for a book I was writing about Southern caves and cavers, but I had an ulterior motive. I had followed Smith’s career since I started caving as a college student in 1980, and I first met him in 1989 in Mexico, where we had joined the same expedition to a deep cave. In 2002, I accompanied him into Rumbling Falls, a massive cave system in Tennessee that Smith helped discover and protect from a proposed sewage plant. I knew he was dealing with the aftermath of a recent caving accident, and I was eager to take advantage of what might be my last chance to explore Mammoth alongside a caving luminary.

Smith grew up in northern Georgia, spending much of his youth touring Civil War battlefields and reading historical accounts of the war. In his early 20s, he started poking into the region’s caves and rediscovered “lost” caves mined for saltpeter during the 19th century. He first saw a Civil War-era signature in a cave in Alabama in 1972 and soon located information on that soldier. These discoveries established what would become his modus operandi for decades.

Douglas started working with Smith in 1991 on a trip to document prehistoric and historic use of Tennessee caves. Douglas was fascinated by his colleague’s encyclopedic knowledge, and the two made plans to study Hubbard’s Cave, a Tennessee bat cave with a few thousand 19th-century signatures. They moved on to other historic caves in Kentucky before applying for a research permit for Mammoth in 2015.

Through most of the war, Mammoth Cave remained open to soldiers stationed nearby, American civilians and even Europeans willing to travel to a war zone. The cave itself had no specific military value, but as surrounding land was seized by the Confederate army and then, in February 1862, by the Union, controlling the natural wonder became a “sign of prestige,” Douglas explained.

“Confederate soldiers would write their name, then Union soldiers would write theirs in the same passage, as though claiming the space,” Douglas said. He described a spot where someone wrote “hurrah for Jeff Davis,” an inscription later scratched out. One cave wall has what researchers believe is a portrait of President Abraham Lincoln.

Our signature hunt began in a hallway of the park’s Science and Resource Management Building, where we crowded around a framed 1908 map of Mammoth Cave showing the routes known during the Civil War. Today, over 400 miles of passages have been mapped, with new discoveries made every year, but in the 1860s only a fraction of those passages had been explored. We decided to take what was known as the “long route” through the cave, starting with El Ghor.

Matt Bransford, a guide at Mammoth Cave, was the grandson of Mat Bransford, an enslaved man and one of the first of many African Americans (including multiple generations of the Bransford family) who served as guides at the cave.

MAMMOTH CAVE NATIONAL PARKWe had a much easier time making our way to El Ghor than visitors 150 years ago did: We went down in an elevator and took a short walk through the Snowball Room — a large white chamber that hosted an underground cafeteria for decades until it was closed in 2013 to avoid contaminating cave life. Reaching this spot in the 19th century would have meant traveling seven or eight hours underground by lantern light. Guides — many of them enslaved African Americans — led visitors through the cave’s complex maze. Abandoned shoes, broken water bottles and bits of torn woolen clothing still dot the most-traveled routes. While such trash would be promptly removed nowadays, these discards are considered part of the cave’s history, and park managers have intentionally left them in place since the national park opened in 1941.

The cave’s inner recesses inspired awe in some soldiers, as recorded in journals and letters. “It was the nicest thing I ever saw,” wrote Union Pvt. George Kryder in a letter to his wife, Elisabeth, dated March 14, 1862. “We went into large chambers like great halls all arched over with solid rock.”

Standing where they had stood, letting my eyes roam over a small section of the wall, I spotted a potential Civil War signature that no one else had noticed. I stared at the delicate cursive, thrilled with the idea that I was perhaps the first to read the simple line in over 150 years. Smith recorded it, Bobo photographed it, and we moved along. We left El Ghor and headed toward the Welcome Avenue, where the narrow corridors and low ceiling required stooping and crawling. The half-mile tunnel provided a shortcut to a graffiti-rich passage.

In September 2017, Smith was nearly killed in a Tennessee pit when another caver accidentally dislodged a fist-sized piece of flowstone that fell 40 feet and struck Smith’s temple just below his helmet. Bleeding from the ears and barely conscious, he somehow climbed out of the pit unassisted and was then airlifted to a nearby hospital for treatment of a concussion and other injuries. For several months before our trip, he had been prone to periods of vertigo whenever he had to stoop or look up, both of which occurred repeatedly as we moved along the Welcome Avenue.

He told the main group to move ahead, saying he would catch up. I stayed with Smith, who walked slowly but deliberately with his carved walking stick. I felt fortunate to spend an hour traveling with him at this slower pace. As we moved along, he spotted and recorded signatures we might have missed had we traveled at a faster speed. We climbed upward, occasionally pausing for him to rest.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›At last we reached the others at the Wooden Bowl Room, which some say was named for an ancient artifact found there by early explorers. From about 5,000 to 2,000 years ago, Native Americans mined gypsum from the cave walls and lit their way with torches made of river cane. I saw black “stoke marks” from torches on the walls, and burned bits of cane lay scattered on the floor. I picked up a hollow, charred piece of cane an inch long and held it to my nose. It smelled of fire.

Continuing toward the cave’s historic entrance, we found new signatures, several of which Smith later identified as dating from the Civil War. We also saw the occasional artwork: a portrait of Andrew Jackson from the 1830s, a woman in a dress, and assorted birds and flowers. Smith called Douglas over to look at a name that was hard to make out. Beside it was the date 1798. If indeed from 1798, the signature would be the oldest ever found in the cave, Douglas said.

By that point, we were nearing the end of our journey, moving slowly because of fatigue. On the way out, we passed wooden saltpeter works from the early 19th century and walls scraped by ancient gypsum miners thousands of years earlier. Finally, after eight hours underground and five difficult miles, we saw the glow of daylight coming around a curve from the natural entrance. Smith slowly marched ahead, and I turned to look one last time at the darkness behind.

About the author

-

Michael Ray Taylor Contributor

Michael Ray Taylor ContributorMichael Ray Taylor teaches journalism at Henderson State University in Arkansas and is the author of several books on caving and cave science. This story is adapted from his new book, “Hidden Nature: Wild Southern Caves,” published by Vanderbilt University Press.