Winter 2021

The Farthest Edge

Chasing solitude — and Thoreau — on the Outer Beach of Cape Cod National Seashore.

At the crest of the first dune, the pickup halted, then it rolled forward slowly, rocking like a boat on a swell. Behind the wheel, Janet Whelan explained that the tires were deflated to 11 pounds of pressure so the truck would handle better on the sand roads. At times, it felt like the vehicle was in charge, she told me. “You sort of let it drive,” she said.

Thoreau described Cape Cod as “the bared and bended arm.”

© KAREN MINOTWe were less than half a mile from U.S. Route 6, the main thoroughfare that runs the length of Cape Cod, and already I felt civilization falling away. All around us were wheat-colored dunes, bright in the October sun and carpeted with tufts of beachgrass. On blind curves, Whelan honked the horn in case other vehicles — most likely SUVs from Art’s Dune Tours, a park concessionaire — were headed toward us.

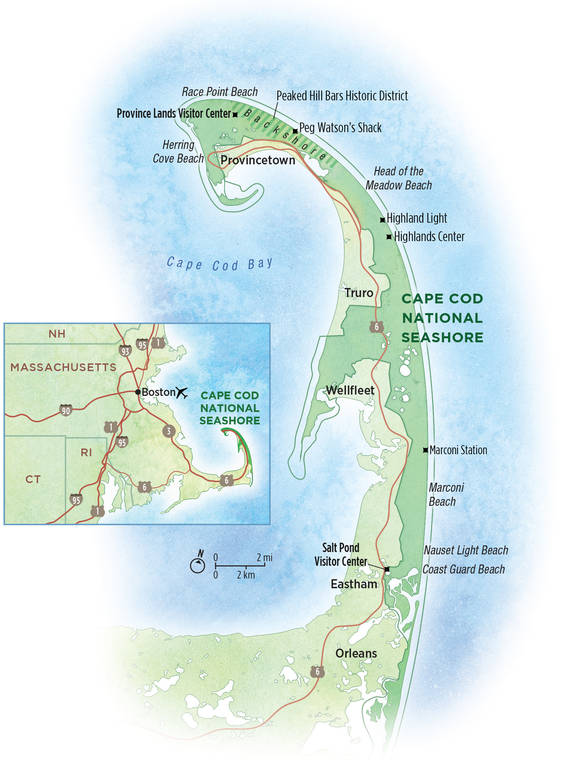

Our destination was a cluster of rustic dune shacks strung along Provincetown and Truro’s so-called “backshore,” arguably the wildest, remotest part of Cape Cod National Seashore’s 40 miles of protected beach. Thanks to a fortuitously timed last-minute request, the opportunity to spend time in a shack had unexpectedly materialized. Whelan, a local doctor and the chair of the Outer Cape Artist in Residence Consortium, was driving me out to the sea, where I’d be hunkering down for the night just before the structures would be buttoned up for the winter.

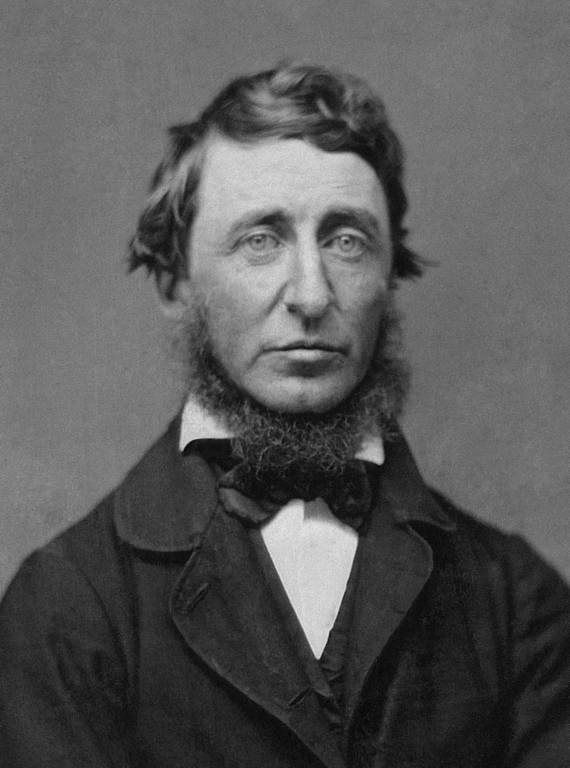

I’d come to the seashore on the trail of writer Henry David Thoreau, who walked a significant stretch of the cape’s backshore in 1849. I was familiar with his oft-quoted book, “Cape Cod,” chronicling his three trips to the area. But though I’ve lived in Boston for almost 20 years, visited Thoreau’s grave in Concord, Massachusetts, and floated in Walden Pond, I’d spent almost no time on the cape, the hooked peninsula that famously flexes into the Atlantic. Thoreau described it as “the bared and bended arm.”

On this visit, I intended to use Thoreau’s travels as a rough guide for my own. I’d spend three days there mid-fall, as he had on his first trip to the cape. “In autumn,” he wrote, “the thoughtful days begin, and we can walk anywhere with profit. Beside, an outward cold and dreariness … lend a spirit of adventure to a walk.” So far, the weather was in the mid-50s, oddly spring-like, but I hoped for some of that spirit. And more than that, I wanted to be alone — really alone, in a way our restless, wired culture rarely seems to allow — and feel a sense of what Thoreau called “the solitude … of the ocean and the desert combined.” Within a few months, the COVID-19 pandemic would demand far more physical isolation than I’d ever wish for. But at that moment, though I didn’t yet know the term, I craved a kind of voluntary social distancing I figured Thoreau would appreciate.

As we trudged up to the shack where I’d stay — known as Peg’s, for Margaret Watson, its original owner, who lived in the structure for 30 years — I caught sight of its pitched roof in the swaying grass. I felt a sudden surge of relief, then nervous excitement. Just over the barrier dune, waves churned against the beach. I’d come for solitude, and here it was.

On October 11, 1849, Thoreau and his friend, William Ellery Channing, arrived on Cape Cod in the wake of a nor’easter, carrying umbrellas. Their aim was to hike roughly 28 miles along the blustery beach from Eastham to Provincetown. I wasn’t ambitious enough to attempt their journey on foot. Though I planned to take some long walks, I’d be driving alongside their route, stopping at points of interest. In lieu of staying with an oysterman’s family and a lighthouse keeper, the lodging the two men had arranged, I’d booked a couple of Airbnb rooms on either side of my shack stay.

The author came to the seashore on the trail of writer Henry David Thoreau, who walked a significant stretch of the Cape’s backshore in 1849.

NATIONAL PORTRAIT GALLERYThe day before my ride through the dunes, shortly after arriving on the cape, I’d driven into Eastham past shingled houses and a smattering of ghosts and pumpkins (Halloween was a week away). I noticed some eateries and shops were already shuttered for the winter. Back in Thoreau’s day, the term “off-season” didn’t exactly apply; Cape Cod was mostly farms and fishing villages. The Cape Cod Branch Railroad — which operated the train he and Channing rode to Sandwich before taking a stagecoach to Orleans — had opened a line between Boston and the cape just the previous year.

“Thoreau was forecasting the allure of the Outer Cape a good half-century before most hotels and inns started catering to people,” explained Bill Burke, the national seashore’s cultural resources program manager. “His writing was evocative of the unsophisticated, untamed, highly rural, isolated Cape Cod.” It would be decades before vacationers and artists flocked to the backshore for its beaches and pristine light, and a hundred years before the tourism boom of the 1950s yielded the area’s first epic summer traffic jams.

Cape Cod National Seashore was authorized by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, after local communities pushed back against tourist-related development. It was one of the first national park sites to incorporate large amounts of private property within its boundaries, and staff were tasked with negotiating more than a thousand individual land transactions, a process that took more than two decades. The resulting 43,000-acre park is a patchwork of public, private and other municipal lands comprising much of the Outer Cape and surrounding waters, and managed by park staff, towns and other stakeholders. The national seashore’s beaches, walking and biking trails, and historic sites now attract millions of visitors each year.

My first stop after circling through Eastham was Salt Pond Visitor Center, near where Thoreau and Channing turned off a dirt road toward the beach. As I followed the 1.3-mile Nauset Marsh Trail beside Salt Pond, a cormorant flapped across the water, and I saw markers where, I’d learned inside, baskets of farmed oysters were submerged. Eager to continue up the coast, I headed north to the Atlantic White Cedar Swamp Trail in Wellfleet, where a boardwalk swerves through an undulating, mossy grove of trees.

By then, I was more than ready to see the ocean, so I crossed a parking lot to the Marconi Station site. In 1903, four antenna towers built by Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi sent the first two-way transatlantic telegraph message from the U.S. to England and back, a feat that helped him earn a Nobel Prize in physics. The station was shut down in 1917, partly due to erosion of the 70-foot bluff on which it sat. Now, only a few concrete tower footings remain, surrounded by heathland. Standing on the cliff, I stared out at blue-gray waves, while a solitary walker tracked across the sand below.

Thoreau, whose brimmed hat featured a special shelf for storing plant specimens, had a romantic fascination with the cape’s flora and fauna, but he also maintained a fatalistic impression of the coast. “I wished to see that seashore where man’s works are wrecks,” he wrote. In the 1700s and 1800s, shoals off the cape caused hundreds of shipwrecks, leading the U.S. government to set up an official lifesaving service in 1871, which was later folded into the Coast Guard. The only souls Thoreau and Channing met on the beach were “wreckers,” who gathered stray cargo and driftwood, and sometimes encountered bodies that washed ashore.

For Thoreau, the unforgiving landscape offered a certain clarity. “The seashore is … a most advantageous point from which to contemplate this world,” he wrote. “It is a wild, rank place, and there is no flattery in it.” When I arrived at Marconi Beach, I felt some of the pensiveness Thoreau describes, but I was also struck by the shore’s stripped beauty. The outgoing tide had carved furrows in the sand, which was littered with thousands of colored rocks. As I picked along the beach — finding clam shells and a brick with rounded edges — I thought I spotted a surfer in the waves. Then I realized it was a seal. Its slick head periodically surfaced and bobbed, watching me.

Since the signing of the Marine Mammal Protection Act in 1972, harbor and gray seals have proliferated on the cape, after being nearly wiped out of the area by hunters. The population is now in the tens of thousands, by some estimates, but the surge has lured predators. In 2018, Cape Cod had its first fatal shark attack in 82 years. The following year, the Atlantic White Shark Conservancy logged over 200 shark sightings off the coast, using a public tracking app that alerts beachgoers in real time.

Later that evening, after parking at the Bookstore & Restaurant in Wellfleet, I was drawn across the street to Mayo Beach, where the sun was setting over the calm bay. The sky was deep purple, with a smear of orange that pulsed before fading out. I stood for a minute, stunned, then wandered back for a delicious fried clam roll and a dozen briny oysters.

The next morning, turkeys grazed at the roadside in Truro as I drove to Highland Light, which sits on an enormous bluff, beside a golf course. The lighthouse is the oldest on Cape Cod, built in 1797 (though the original wooden structure was replaced by a brick tower in 1831, then rebuilt in 1857). After he stayed with the keeper, Thoreau remarked on the crumbling cliff beneath the lighthouse, predicting that “erelong, the light-house must be moved.” It wasn’t until 1996, however, that the lighthouse was shifted 450 feet back. According to Park Service estimates, the cape’s shoreline erodes about 3 feet per year, and rising sea levels due to climate change are expected to accelerate that process. Of the 10 acres originally acquired by the government to build the lighthouse, six have been lost to the sea.

I made quick stops at the Highlands Center — an abandoned U.S. Air Force station now used as an arts and research hub — and Head of the Meadow Beach, where a salt meadow spreads out like a savanna. But farther north, the dunes were calling: Soon I was rushing off to catch my ride to the shack. I parked my car on the shoulder of Snail Road, then found Whelan and Bette Warner, the executive director of Peaked Hill Trust, a nonprofit group that manages five of the 19 shacks on the backshore. Except for one, all the shacks are owned by the park and are considered historic properties for their unique architecture and ties to notable artists who lived and worked in them. The trust runs an annual lottery among its members for one-week stays and manages an arts and sciences residency program, one of several such shack residencies.

In the 1800s, the earliest shacks were intended as temporary dwellings for stranded sailors, “surfmen” on lifesaving patrols or fishermen. By the early to mid-1900s, as Provincetown’s arts colony began to take shape, new shacks were being built by bohemians and others seeking isolation. Playwright Eugene O’Neill moved into the Peaked Hill Bars Life-Saving Station in 1919, stirring interest in the backshore as a source of inspiration. In the ensuing decades, writers and artists such as Josephine Del Deo, Mark Rothko, Jack Kerouac, Cynthia Huntington and Annie Dillard would all spend time in shacks.

Though many used the dwellings for creative escape or recreation, others, such as Peg Watson, a social worker, and poet Harry Kemp, became full-time residents, determined to live a subsistence lifestyle. A 2005 ethnographic study of dune shack culture by the social anthropologist Robert Wolfe, commissioned by the Park Service, identified around 250 year-round residents and as many as 1,700 seasonal users over a century of shack use. Some shack dwellers cited Thoreau and the writer Henry Beston — who spent a year in a dune cottage in the 1920s — as early models for their back-to-the-land ideals.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

Since the national seashore’s designation, the shacks have periodically been the source of tension between shack users and the Park Service. With no electricity or indoor plumbing, the primitive structures were initially seen as a blight, and several of the original 28 shacks were demolished during the park’s early years. “The intent early on was that they would all be removed, it was just a matter of time,” said Burke, the park historian, noting that some of the shacks were burned by vandals or lost for other reasons.

Over time, however, more people began to advocate for the shacks. In the early 1980s, the shack of Charlie Schmid — a full-time dune dweller known for his studies of swallows — was razed just after his death. The event spurred a new campaign to save the dwellings, and though it took decades, the preservationists eventually prevailed: A 1,950-acre historic district protecting the shacks and surrounding land was formally created in 2012.

After the bumpy ride through the dunes and a few stops to pick up outgoing residents at other shacks, I found myself alone in Peg’s. Padding around in my bare feet, I noticed decades’ worth of do-it-yourself touches: spoons bent into coat hooks, an ingenious weight-and-pulley system for keeping the windows open, a guitar lashed to the ceiling.

Outside, I walked across the cool sand past beach roses and cedar-slat fencing to a bench made of salvaged wood overlooking the sea. I tried to imagine living there, making coffee on the propane stove, pumping water from the well, hearing the wind against the shack’s walls, day after day. Already, I felt a connection to the quiet, bare-bones space. I figured I could get used to constantly sweeping out sand, and even relying on an outhouse. But I also wondered: Even in such a charming place, how does anyone adapt to so much solitude? I thought of Thoreau in his cabin at Walden Pond and the occasional trips he made back to town for supplies and his mother’s cooking.

In late afternoon, I bounded down the barrier dune to the beach. As I walked along the shore, tiny plovers scurried beside me, and gulls stood in rows like soldiers, watching the surf. I came across some ancient wood, frayed like a coconut shell. A hunk of an old wreck? On the barren coast with no people in sight, it felt like I was seeing the same landscape Thoreau saw, but I knew the cape’s shoreline is continuously resculpted by waves and wind, and the beach he walked was swept away long ago. Thoreau himself was aware of the speed and power of coastal erosion, writing that the cape’s beaches “are here made and unmade in a day … by the sea shifting its sands.”

Back at Peg’s after my ramble on the beach, I ate a sandwich and shook sand from my shoes. As dusk fell, I stood on the bench outside and watched the sunset streak the clouds orange and pink. Soon the sky was overwhelmed with stars. Inside, I made tea and read for a while by the light of oil lamps. Then I buried myself in blankets, exhausted.

SIDE TRIP: Wellfleet Bay Wildlife Sanctuary

It was drizzling when I set off the next the morning, and I worried about getting caught in a storm. Though only about a mile long, the hike out from the shack district is a challenge, but I welcomed the chance to explore more of the dune wilderness. I plodded through deep sand — where I saw ribbons of coyote tracks — and alongside boggy patches where wild cranberries grow. Catching my breath at the top of the last dune, I looked out over a blanket of russet-colored trees. The rain had picked up, but I was almost there. The cars on Route 6 sounded strangely like the ocean.

I did a quick drive through Provincetown, which looked mostly deserted. Once a salty fishing hub — “the most completely maritime town that we were ever in,” Thoreau wrote — the town has evolved into an arts mecca, and for decades has been a haven for the LGBTQ community. It’s now full of trim, expensive houses, many of which are boutique shops, inns or second homes. By October, a large share of the windows have gone dark. I managed to find an open cafe for coffee and an egg and linguica sandwich, then I headed back into the park.

I ended up at Province Lands Visitor Center, just a short distance from where Thoreau and Channing caught a steamer back to Boston, where I’d be returning the next day. On the hexagonal observation deck, I looked out through a foggy gray mist toward Race Point, at the tip of Cape Cod, pausing to acknowledge that I had traced the full arc of Thoreau’s journey. For a brief moment, the 170 years between our experiences felt short.

Describing his return to Concord after his trip, Thoreau wrote, “I seemed to hear the sea roar, as if I lived in a shell, for a week afterward.” I know what he meant; I still hear it now.

About the author

-

Dorian Fox Contributor

Dorian Fox ContributorDorian Fox is a writer and freelance editor whose essays and articles have appeared in various literary journals and other publications. He lives in Boston and teaches creative writing courses through GrubStreet and Pioneer Valley Writers' Workshop. Find more about his work at dorianfox.com.