Spring 2020

Seeing the Light

A weekend getaway to the country’s only national park site devoted to painting.

The grass tickled the back of my legs. As the sun sank in the autumn sky, I opened up a paint-mottled canvas bag and one by one, pulled out the objects inside: four paintbrushes of varying widths, a translucent blue ruler, a No. 2 pencil, a cup of water for rinsing brushes, a clipboard with a sheet of pleasingly thick white paper and a set of watercolors that looked brand-new. I spread all the items on the grass before me and delighted in my bounty. A soft breeze grazed the lawn, and birds chirped and squawked overhead. Looking around, I could see a forest, a meadow, a stone wall and a garden. The landscape summoned me. I picked up a brush and began to paint.

Julian Alden Weir’s circa 1894 oil painting “The Laundry, Branchville,” depicts a scene at Weir Farm.

© WEIR FARM ART ALLIANCEIt was late September at Weir Farm National Historic Site in southwestern Connecticut, where I had come to enjoy a break from my urban life, learn about the park’s history, marvel at the fall foliage and create a little art. Bucolic and serene, Weir Farm is a compact, 68-acre park with a handful of buildings, gardens and trails. The country’s only national park site devoted to painting, the farm is unassuming, easily blending in with the stone walls, tidy gardens and historic homes of the surrounding neighborhood. But the apparent simplicity of the farm belies the remarkable quality of the light and colors there. Some visitors described the landscape as “magical,” which at first seemed to me like an overstatement but after playing artist for the weekend, I understood what they meant.

“The most important thing you can do here is paint, draw, make art,” said Superintendent Linda Cook. “When people come here and try art, they let down their defenses in many ways. It allows you to be still in a park setting — to focus and observe and look at things longer.”

I knew very little about Julian Alden Weir, considered by some to be the father of American impressionism, when I signed up for a free evening painting class at the park. I had been craving some creative time away from my computer, and the fact that I hadn’t painted in years did not deter me in the least. The farm, I learned, has a long history of serving as a retreat from the city. Weir first arrived here by train from Manhattan in 1882, seeking an environment he thought would be conducive to art-making. The property, eventually covering 238 acres, became Weir’s sanctuary and muse — and a second residence for his family. He continued journeying there for nearly four decades until his death in 1919 at age 67.

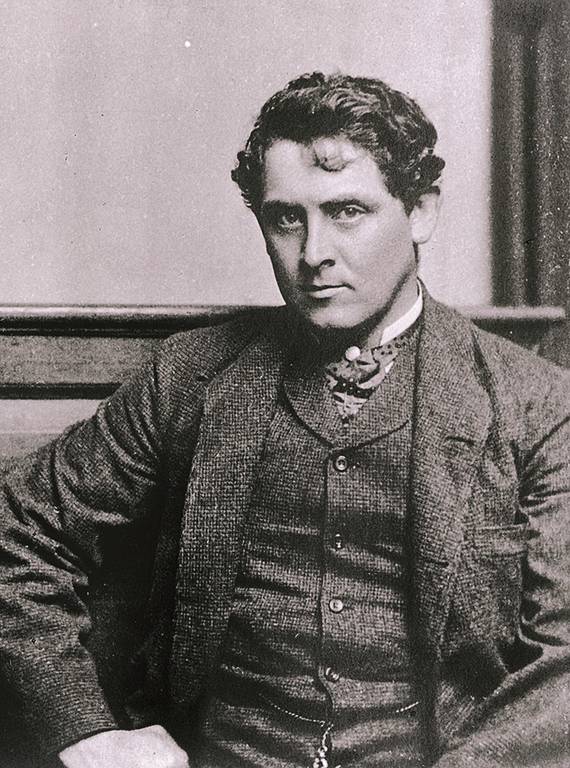

Weir in an 1883 photograph taken on his honeymoon in Europe.

NPSThe 14th of 16 children, Weir was the son of Robert Walter Weir, a professor of drawing at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. (Weir’s brother John Ferguson Weir became the first director of the Yale School of Fine Arts). He studied art in Europe from 1873 to 1877 and after returning to New York City, he painted, taught art, and worked as an art buyer and collector. In 1882, one of his wealthy clients proposed trading an abandoned colonial farm he owned for $10 plus a painting Weir had recently purchased that the client particularly liked. Weir accepted the offer.

Trained in a rigid, detailed style and known for his still lifes, Weir initially disliked impressionism, which he had first encountered in France at an 1877 exhibition by Claude Monet and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. During his early years at the farm, he painted mostly dark-colored family scenes of his wife and daughters. By the late 1880s, however, Weir had developed a robust appetite for painting landscapes in a less conservative style. He painted en plein air, capturing whatever was happening in nature at the moment. By 1891, critics were calling him an impressionist, noting a lighter, brushier, more experimental style; he would continue to paint this way for the rest of his life.

“Weir is one of the few truly direct links between American and European impressionists,” said Yale University Art Gallery Curator Mark Mitchell. “By the time Americans are turning to it in the 1890s, the impressionist movement in France had ended.” Mitchell said impressionism on both sides of the Atlantic depicted modern life and the middle-class fantasy of escaping by train to the beach or countryside. The Americans, however, focused more on landscape painting than their European peers, and their brushwork was typically faster and looser.

Visitors can hike on a network of trails that wend their way through the park and the adjacent Weir Preserve. The park grounds are open year-round, sunrise to sunset, for walks, art-making, dog-walking and self-guided tours.

© GASTON LACOMBEWeir’s hilltop farm, where he grew corn, cabbage, beets and apples, influenced not only Weir but also his three daughters, as well as visitors including painters John Singer Sargent, John Twachtman and Albert Pinkham Ryder. Today, artists visit year-round with their easels and paint in much the same way as Weir and his contemporaries.

Cook said she is still amazed, after 15 years at the park, that a relatively modest place has sparked such creativity through the decades. “It’s not by water, there’s no spectacular views of mountains, it’s not a majestic landscape, it’s not a Western vista,” said Cook, whose family couldn’t afford to go to national parks when she was a child but who now has worked for the National Park Service for three decades. “It’s subtle — the stones in the wall or the way the light filters through the trees.”

After arriving on a Friday afternoon, I toured Weir’s home and examined some of his original works, including his self-portrait and “Early Moonrise” in the living room and “Autumn” in the dining room. (The park owns 175 of his pieces, including oils, watercolors, etchings and sketchbooks; Weir’s art can also be found around the world in museums, galleries and private collections, including The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, the Brigham Young University Museum of Art and The Phillips Collection.) As I walked around the rooms, decorated with ornate wallpaper and furnishings Weir shipped from Europe, I glanced outside and imagined Weir looking out the same windows. The park’s “Painting Sites Guide” brochure maps out the real-life scenes depicted in paintings by Weir and other artists.

Weir curated everything on the farm from the living space to the landscape. To create his romantic ideal of a farm, he had fields mowed a certain way, used oxen instead of machinery, and added stone walls and rustic fences. In 1896, he built a pond using prize money he’d won when a painting he had entered in an art show took first place. Today, the park is mandated to maintain the look Weir cultivated and goes to great lengths to do so. A red oak by Weir’s studio, for instance, gets extraordinary care from a tree company — including annual deep root injections, a fertilization process.

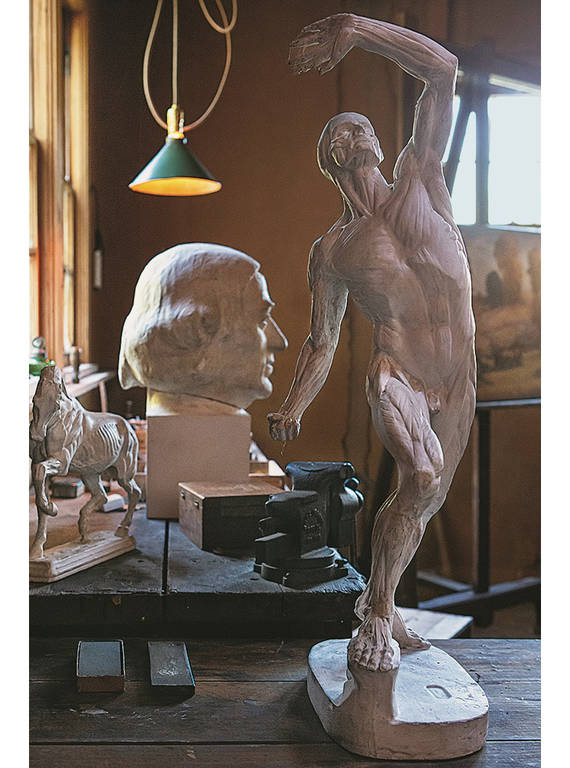

The studio of sculptor Mahonri Young, who married Julian Weir’s daughter, Dorothy Weir.

© GASTON LACOMBEFriday evening, I joined the park’s last yoga class of the season, held in one of the formal gardens. “Nature has a way of slowing us down,” the instructor said. The last light of the day bathed her face in color; she moved a fat worm off her mat. “You may have a lot of sensations flowing in the body. Don’t miss anything.”

As I lay on my back at the end of class, I watched a bee hover by a raspberry bush and a dragonfly dart in a “Z.” Above, wide brushstrokes of clouds filled the sky.

Saturday, still feeling the calming effects of the yoga class, I walked around Weir’s pond and back toward the farmhouse, which was originally built in the late 1700s. The morning sun hit the yellow and red leaves in a way that made them flicker like sequins. Behind the house, I visited the studio of sculptor Mahonri Young (grandson of Mormon leader Brigham Young), who married Weir’s daughter, Dorothy Weir. Another daughter, Cora Weir Burlingham, lived with her husband in a house on the property that later became the visitor center. Along with Doris and Sperry Andrews, the last residents of the farm, Burlingham helped organize a grassroots movement to preserve the land and buildings that in 1990 became Weir Farm National Historic Site.

On the lawn in front of Weir’s home, I found artist-in-residence Alissa Siegal painting one of her favorite trees. The park hosts a different artist each month, February through November, and I’d heard it was Siegal’s final day.

“Do you want to see my studio?” she asked. She left her easel in the middle of the lawn, and we walked across the street. The modern space was flooded with light, and Siegal pointed out the work she’d created during the month, including papier-mache flowers and acrylic and charcoal paintings of animals. Though she’s been creating and selling art for decades, she said she hadn’t had so much concentrated time for art since graduate school.

“To have someone invite you to be part of this historical lineage — and have no constraints and no requirements other than coming here and making art — is pretty magical,” said Siegal, who lives in Stamford, Connecticut, and teaches art at The Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum. She said she appreciated the connection to the artists who came before and enjoyed seeing how each had responded to the place. Her experience here mimicked Weir’s in some ways — she spent her time outdoors, watching the light change throughout the day and recording impressions with quick paintings.

SIDE TRIP

Late that afternoon, I picked up the canvas bag of art supplies from the porch of the visitor center. Colored pencils or watercolors are always available to borrow when the building is open, May through October, and visitors can take them anywhere in the park. Cook told me that the staff takes great pride in offering high-quality supplies and cleaning them carefully between uses; the message is that everyone, regardless of experience or skill, is treated like an artist here.

I walked to the middle of the lawn and plopped down in a spot facing a stone wall and the forest. Feeling exhilaratingly unhurried, I contemplated the blank paper for a while before finally picking up a pencil. With light strokes, I sketched stones and branches. Then I opened my watercolor box and added color, watching watery blues and greens pool, swirl together and fade. The familiarity of these motions was palpable and welcome — down to swishing a brush in the cup and watching the water turn a new color with each rinse.

After dinner in town, it was time for class. Dmitri Wright, who calls himself an evangelist for impressionist plein-air painting, has taught at the park for more than a decade, and regulars from the area flock to his classes. Inspired by painter Albert Pinkham Ryder as a young man, Wright came to understand that plein-air works rely on senses other than sight. Those other sensations are particularly handy when one is painting outside at night.

“The sound of crickets becomes louder, you hear the owls talking to one another,” Wright said. “Since you can’t see the painting that well, you have to trust your instincts and use your gut. Don’t worry if your painting looks very childlike. Impressionists say, ‘Paint your own naive impression.’” Wright stressed the importance of keeping our palettes organized so we would know where the colors were once it got dark. He assured us that our eyes would adjust.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

At twilight, our class of a dozen, mostly women, picked spots and set up easels. Siegal was there, and I met a number of other local artists, including a professional illustrator who lives in New York. She told me she likes painting at the park because of the vibe: “You can feel the other artists.” Other women said they felt safe setting up and painting there, even when they were on their own.

I squeezed acrylic paint out of several tubes onto my palette then suddenly felt paralyzed, realizing Wright’s short talk in the classroom was our only instruction; it seemed that all the other artists were experienced enough to know how to proceed. I could see Siegal painting bold, sinuous branches across her canvas and the illustrator carefully painting a building. I asked Wright for advice.

“Breathe in, fill your belly, be in the moment,” he said. He stepped away from the easel, turned sideways and stood in a fencing position. Then he bent his knees and stretched his arm out like he was about to slice up the canvas.

I laughed nervously and tried to mimic Wright’s stance, trusting that these movements would result in something artistic and not completely humiliating. The landscape I’d chosen just 30 minutes earlier had transformed into murky shapes under the darkening sky, so I tried to follow Wright’s instructions and paint by feel. At first, I took care not to mix colors unintentionally, but in no time, my palette was a jumble of hues. As I added details to my scene, I surrendered to the darkness and the intermingling paint, brushing a confusion of color onto my canvas. Somewhat arbitrarily, I decided the painting was finished. When I brought it inside, I saw greens, reds and whites swirled around in tree-like shapes.

“Fantastic!” Wright beamed. “You can’t see, so you paint from your heart!”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›“Thank you,” I said, amused but skeptical. I looked at my painting and felt the smallest amount of satisfaction, admiring the way some of the thick paint stuck out from the canvas.

The next morning, eager to savor the last few hours of my visit, I woke early enough to catch a sunrise at the park. I sat on Weir’s porch in a rocking chair, watching chipmunks scamper along stone walls and listening to acorns pelting the lawn. With every gust of wind, a shower of brittle leaves twirled to the ground.

Just two hours later, I was on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. Horns blared, sirens wailed, handcarts rattled. As I drove up Broadway, I recalled the line from a letter Weir wrote to his mother-in-law soon after returning to New York from the farm: “We are again in this big turmoil of a city and already wish we were out of it.”

ABOUT THE PHOTOGRAPHER

I entertained no such wishes; I was determined to hold onto the carefree feeling of the morning even as I immersed myself in the commotion of the city. I parked my car on a busy street and strolled for a few blocks, thinking happily about my rural getaway. Then I stopped cold. My painting! In plain sight on the back seat of my car! Of course, it was preposterous to think that someone could mistake my childlike artwork for something of value. But decades of city living and two broken car windows have taught me not to leave anything visible in my car — even something, ahem, worthless.

I turned around and walked back to my car. Chuckling at the thought of someone stealing my painting, I covered it with an old sheet. Then I locked the doors and headed up the block again, my pace quickening with each step.

About the author

-

Melanie D.G. Kaplan Author

Melanie D.G. Kaplan AuthorMelanie D.G. Kaplan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer. Her book, "LAB DOG: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research," will be published by Hachette in 2025.