Spring 2020

Homecoming

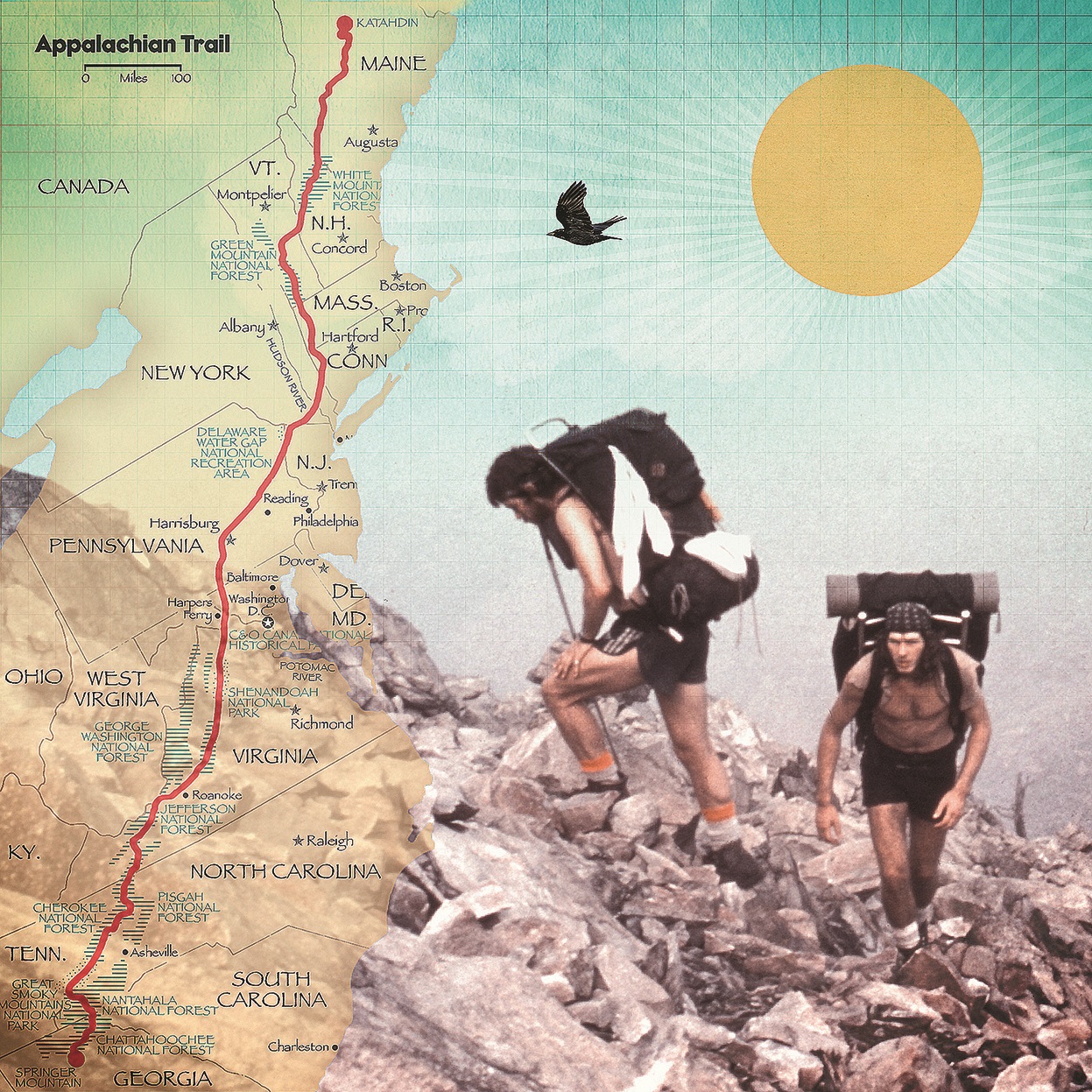

Exactly 40 years after completing the Appalachian Trail, nine hikers reunited in Maine. How had walking those 2,193 miles changed the course of their lives?

On a crystal, cold, late September day, five of us stand at the summit of Mount Katahdin. The seemingly limitless Maine woods stretch out far below in shades of green, scarlet and orange. The wind is as sharp as the sun is warm. We are exhilarated and exhausted at the same time.

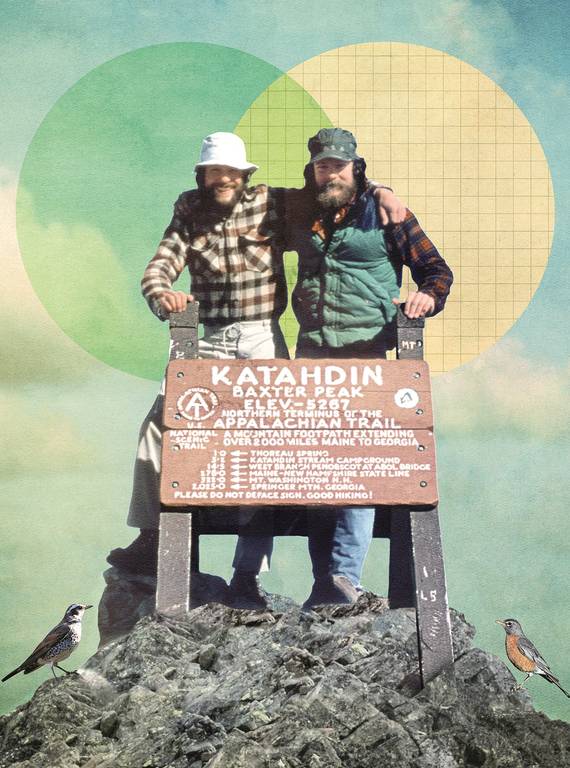

In the Abenaki language, Katahdin means “the Greatest Mountain,” and it is easy to understand why it was so named. At 5,267 feet, it is a dominating presence in this stunningly beautiful landscape of lakes and trees. It is also the northern terminus of the 2,193-mile Appalachian Trail.

Our group of gray-headed 60-somethings — Dave, Jeff, two Pauls and me — squint-smile at each other through the brightness and the gusts. Precisely 40 years ago, this little band, along with 12 other hikers, had celebrated a life-altering moment at this very spot: the final steps of a multi-month, end-to-end walk along the AT. Today, Katahdin, a fulcrum point in all our lives, draws us back again.

We all set out from Georgia in the spring of 1979. Dave Brill and I had met at a lecture in a backpacking store in Arlington, Virginia, a few months before we planned to attempt our respective hikes. The speaker, who had thru-hiked the AT a few years earlier, asked if anybody in the audience was planning to hike the entire trail that year. Two hands rose. We sought each other out after the lecture, loaded up on what now seems like immensely heavy equipment and shoes and decided to begin the hike together.

The others had started at different times and hiked at different paces, but as we neared the end of the trail, snow (or the threat of it) inspired some to hurry and others to slow down, and we drew closer to each other. In the end, 17 of us gathered for a summit photo on September 27, 1979, an extraordinary number considering that only around 130 hikers are known to have completed the end-to-end hike of the AT that year.

We had literally and psychologically started in one place and ended in another. After months of sharing the exquisitely simple daily routine of long-distance hiking — walk, eat, laugh with your friends around camp, sleep, wake, start again — we’d finally reached our goal. From this vantage, we could see the spectacular landscape stretching north into Canada. But what lay ahead in our lives? That was not as clear.

Dave Brill (left) and Paul Dillon on the Appalachian Trail in Pennsylvania in July 1979. © SONIA ROY

At the summit of Katahdin this September, Dave and I brace ourselves against the 25-mile-per-hour wind to grasp each other around the shoulders. We are celebrating not only the 40th anniversary of our walk, but also the way our lives have been connected since, through loves and trials, children and careers. We conjured the idea behind this reunion and tried to send the word out, never expecting more than a couple others to show up.

To our astonishment, seven of the original 17 hikers joined the two of us. Those who were able to agreed to hike up the mountain together, having conveniently forgotten the difficulty of this stretch of the trail — which climbs 4,200 vertical feet over 5.2 miles — and perhaps not accounted for the difference four decades make. After 3.5 miles of extraordinarily steep hiking, the hard part begins — tricky bouldering at a 45-degree angle with 2,000-foot drops on both sides. At points, the only way forward is to grasp a rebar handhold drilled into the granite, which requires a fair amount of upper-body strength. This heart-pumping experience is followed by an additional 1.5 miles of horizontal hiking above the tree line on open, rocky land and a final 700-foot ascent to the summit.

Reunion attendees included (from left) Paul Phillips, Paul Dillon, Gary Owen, Cynthia Taylor-Miller, Dave Brill, Jeff Hammons and Robin Phillips. © SONIA ROY

Our legs are wobbly, but here we are, gathered once again around the weathered sign at the apex of the Greatest Mountain. Paul Phillips, a physician from Florida, completed the alter ego of the AT, the Pacific Crest Trail, before entering medical school. Jeff Hammons, nicknamed “Kansas” during the original hike in honor of his home state, has lost none of his wry Midwestern wit over the years — and very little of his stamina. He still hikes frequently, usually through the desert ranges of the West, and works as an elementary school teacher on the Navajo Nation Reservation. Paul Dillon falls into deep conversations as easily as anyone I’ve known. A leggy ski bum from New Hampshire when we met him, he was always the most athletic of hikers, effortlessly striding across the landscape. He’d pick up a guitar wherever he could find one as we walked north in 1979, and today, he’s a musician in Seattle. It’s Paul’s birthday today, as it was the last time we were here together 40 years ago. Dave, a writer with a shock of unruly hair and boundless humor, lives in Tennessee. He is the author of several books including “As Far as the Eye Can See,” the story of our 1979 hike, which is still in print after 30 years.

MORE NOTES FROM THE TRAIL: A SEASONED GREETER

In spirit (and a photograph), Nick Gelesko — the “Michigan Granddad” — is also with us. He was in his 50s in 1979, when we met him in Georgia. After losing touch for several states, Nick caught up with us in New York, and he, Paul Dillon, Dave and I hiked the remainder of the trail together. Twenty years later, Gelesko, who was then 77 and had recently recovered from carotid artery surgery, joined Dave and me for a reunion hike at Katahdin. I distinctly remember his black beret and quiet smile of satisfaction as he stood proudly at this point that day. I am still in awe of the man, who died at age 94 in 2016.

Farther down the mountain, still working his way up, is Paul Phillips’ brother, Robin Phillips. The brothers completed the trail together in 1979 and today live a few miles apart in Florida, where Robin is a professional photographer. (Later that evening, when we viewed slides from ’79, Robin laughed uproariously at photos of his skinny, 20-something self standing naked in a creek in Virginia.) With Robin is Gary Owen, a tall, smiling Tennessean. He recently retired from his work at a science and technology laboratory, and he and his wife drove their recreation vehicle from Knoxville to be with us. Jim Schaffrick, a soft-spoken woodworker from Connecticut who sat around dozens of campfires with us 40 years ago, chose not to pursue the steepest part of the climb and had walked back to our cars to await our return. Finally, just outside Baxter State Park, nursing a soon-to-be-replaced hip, is Cynthia Taylor-Miller, one of the few female thru-hikers in 1979. Though she and I did not get to know each other well during our original hike, we had reconnected recently through our trail-related volunteer work. Cynthia now gives back as a trail-maintainer and hiking club officer in Vermont.

My decision to hike the length of the AT in 1979 was born of a vague sense of restlessness. For years I’d done what I felt was expected of me: I’d worked hard in school, graduated from a prominent university and secured a good job as a land planner at a large corporation. But it seemed like I was stuck in someone else’s life. I didn’t fit easily into the corporate culture in my workplace, and I felt disconnected from the suburbs of Washington, D.C., where I lived. The economy was in recession, my dad was becoming crippled from rheumatoid arthritis, and the Three Mile Island nuclear accident had just happened, shaking my faith in the certainty of science and political leadership.

I had only limited experience in the outdoors — some Boy Scout camping, a couple of trips to the mountains in college — but the idea of embarking on an odyssey drew me. I sought an extended journey, a vision quest toward … well, something, and to my parents’ chagrin, I was willing to blow off the stability I’d just attained to do it. I quit my job, positioned myself on Springer Mountain in Georgia with my newfound friend, Dave, and started walking north.

The AT is generally not a destination in itself; it is a journey toward something else, a concept many hikers really don’t preconceive. They take the first step on faith. Earl Shaffer, the first person to complete a documented end-to-end hike of the Appalachian Trail, was trying to walk off World War II when he began that first trek in 1948. A sizable contingent of veterans do the same today, hoping to exorcise some of the demons they met in wartime. I hadn’t faced that kind of trauma, but I was determined to slough things off, pare down, reorient, fling myself in a new direction. Jettisoning baggage, from my head as well as from my pack, became an important part of my experience.

Completing the AT in a single season is no easy task. Roughly three in four of those who attempt to become “2000-milers” fail to complete the hike in the year they set out. Most leave the trail in the first few weeks, falling victim to homesickness, loneliness, boredom, injury or the mental and physical challenge of walking up and down mountains every day, often in the rain. But those who stick it out are rewarded with membership in a unique community that forms during hour upon hour of walking and at stops along the way. (In the pre-cellphone era, the chief way we communicated with friends who had sped ahead or slipped behind was through trail registers, little notebooks placed in many of the shelters by volunteers.) By the time we reached the Maine woods, we had become family, and standing on top of Katahdin was like Sunday dinner, a celebration of togetherness.

And then it was over. I recall the letdown of being back in a car, leaving Maine and driving down I-95 back toward Washington. Looking out the window at other drivers, I thought about how much I’d changed during my time on the trail and how the world around me had not. My trail family scattered, and for the most part, everyone struggled to figure out their next steps. Dave went back to Cincinnati, where he grew up, and worked in odd jobs until he set out on another long hike on what later became the Pacific Northwest National Scenic Trail. Eventually, he went to graduate school in journalism and started writing professionally. Paul Dillon moved to Santa Fe for a time. Paul Phillips took off on a journey around the world. I was simply not ready to reenter the world I’d left, so I returned to Hot Springs, North Carolina, where an innkeeper Dave and I had met while hiking had offered me a part-time job, room and board, and a chance to find my path.

Daniel Howe (left) and Dave Brill at Katahdin in 1979 after becoming 2000-milers.

© SONIA ROYThat move made all the difference. I apprenticed to a harpsichord maker, learned how to build the hammered dulcimer — an ancient ancestor of the piano — met other local musicians and played the haunting music of the Southern Appalachians on my guitar and the dulcimer. The AT follows Main Street through town, which allowed me to wander into the surrounding ridges on any given day, and I felt embedded in the landscape. I tended a remarkable bottomland vegetable garden, and my appreciation for the ecology, flora and landscape of the Southern mountains expanded. Inspired, I embarked on what became a 30-year-career as a landscape architect and city planner. In my early 30s, I married, and my wife and I raised a son and daughter. We just celebrated our 32nd anniversary.

Now I teach landscape architecture part-time, and I also serve as a volunteer and board member at the Appalachian Trail Conservancy. My hope is to preserve the opportunity for others to have the sort of trail epiphanies I had, whether they come from day hikes or thru-hikes. My daughter, who is 21, first set foot on the trail nearly 10 years ago and already has indicated her intent to set off on her own end-to-end journey on the AT.

Dave often says he would never have completed the AT if not for me. I think he’s got it backward. Whoever is right, we have profoundly influenced each other’s lives. When Dave’s first marriage was ending, we talked about our children and how to be the best kind of parents to them no matter what turns life presented. Later, when I struggled in my career, I’d head to Dave’s home on the Cumberland Plateau, where we’d share bourbon and mostly true stories around a golden fire. We’d play guitar competently and sing badly late into the night, and after this ritual of talk and song and fire, we’d both feel like all the mountains in our paths were surmountable, and every stiff climb would likely end in a nice view.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Without Dave repeatedly reminding me who I really was, I might have, many times, stepped back onto the path of conformity. In the end, I resisted the temptation to return to the corporate world and found great contentment in my chosen path. As for Dave, he moved on from his divorce to a very happy marriage. He raised two extraordinary, talented daughters and built a magical cabin above a creek in the hemlock woods. My son and Dave’s daughter both got married (to different spouses) on the same day last year, just one week after we returned from the Katahdin reunion.

I can’t quite picture who I would be without Dave. He will always be my first phone call when anything significant, good or bad, happens. (I will, however, have to call his landline because he still refuses to get a cellphone.) And it all started when we walked in the woods for five months and became different people, together.

The afternoon is waning, and our group of old-timers is facing a five-hour hike back to the campground where we’d parked. Even so, we stay an extra few minutes on the rocky summit, hugging each other, taking more photos, making small talk with other day-hikers who hover around the peak. Looking down the steep trail, Paul Phillips suggests that perhaps we should consider a beach vacation for our 50th reunion.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

We greet a hiker who is obviously finishing his own long-distance hike — his gauntness, glow of satisfaction and worn-out shoes give him away. He stops to talk with us for a minute before descending. As usual, there’s a bit of shop talk about the condition of the trail, his start date in Georgia and what he was doing before he started his journey. His face has a wistful cast that I recognize as he looks toward the path he’s about to walk back down, southward. “What are you going to do now?” I ask, shading my eyes from the late-day sunshine. “I don’t know,” he replies. “Something different.”

About the author

-

Daniel Howe Contributor

Daniel Howe ContributorDaniel Howe is a writer, consultant and part-time professor in the Landscape Architecture Department in the College of Design at North Carolina State University in Raleigh, North Carolina. His many national park experiences include thru-hiking the 2,193-mile Appalachian Trail and cycling the length of the 469-mile Blue Ridge Parkway. Howe currently serves on the board of directors of the Appalachian Trail Conservancy.