Summer 2019

Naming Matters

Should Devils Tower be called Bear Lodge? Is Tacoma a better moniker than Mount Rainier? Around the country, activists are fighting to change place names they deem offensive, hurtful or arbitrary, and national parks are frequently the targets of these campaigns.

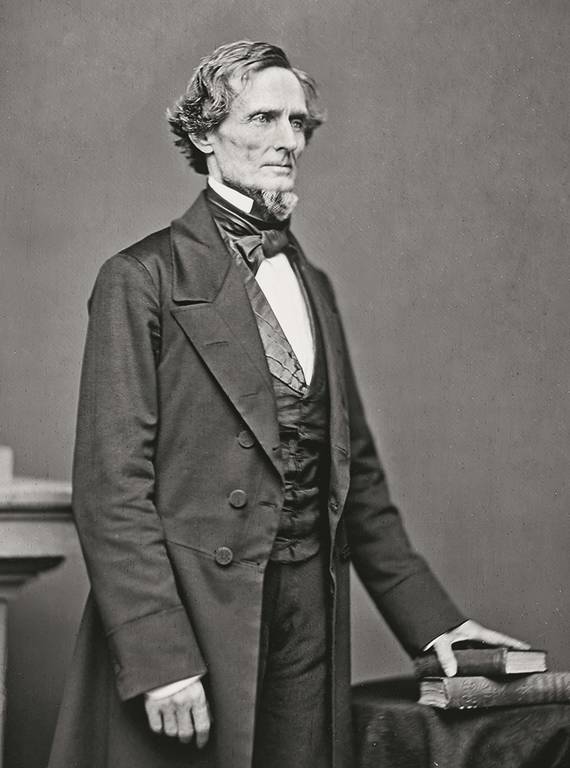

In 1855, a U.S. Army officer was conducting reconnaissance work in the Great Basin on the eastern edge of what would soon become the state of Nevada. Contemplating the area’s most majestic peak, he decided to name it after his superior: Secretary of War Jefferson Davis.

Jefferson Davis

MATHEW BRADY/NATIONAL ARCHIVES AND RECORDS ADMINISTRATIONDavis, as we now know, went on to serve as the president of the Confederacy for the duration of the Civil War, and only a decade after the peak was named in his honor, his side lost the war, and he was sitting in prison and awaiting trial for treason. Government mapmakers no longer saw Jeff Davis Peak as an appropriate moniker for Nevada’s second-highest mountain. They toyed with a few replacement options, including Union Peak and Lincoln Peak. Eventually, they settled on Wheeler Peak in honor of another officer who had surveyed the area, but they didn’t discard the old name. Instead, they assigned it to a lesser summit nearby.

For more than a century, nobody seemed to give Jeff Davis Peak much thought. That changed in August 2017, when Anthony Oertel, a Bay Area resident, was inspired by the activists behind the effort to remove statues of Confederate generals in Charlottesville, Virginia. Oertel, who had never set foot in Great Basin National Park where the peak is located, filed a request with the U.S. Board on Geographic Names to rename the mountain after Robert Smalls, an enslaved man from South Carolina who orchestrated a daring escape during the Civil War and later was elected to the House of Representatives.

It took an article in a Nevada paper for locals to notice, and notice they did. State newspapers ran opinion pieces about the controversy, a member of Nevada’s legislature sponsored a resolution supporting changing the name, and representatives of the Nevada State Board on Geographic Names, who submit recommendations on local names to the national board for final approval, received a flurry of passionate letters.

“You have my vote to change the name of Jeff Peak and any other landmark named after Confederate traitors,” wrote one local. Others criticized what they saw as undue political correctness. “Please help stop the madness in this country and leave the name alone,” a Reno resident pleaded. A high school student suggested naming the peak after Heather Heyer, the woman who was killed while protesting a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville. Lonnie Feemster, the president of the local NAACP chapter, wrote that the peak should not honor a man who fought the Union, which Nevada joined during the Civil War.

“Some things are history, and some things are errors that need to be corrected,” Feemster said in an interview.

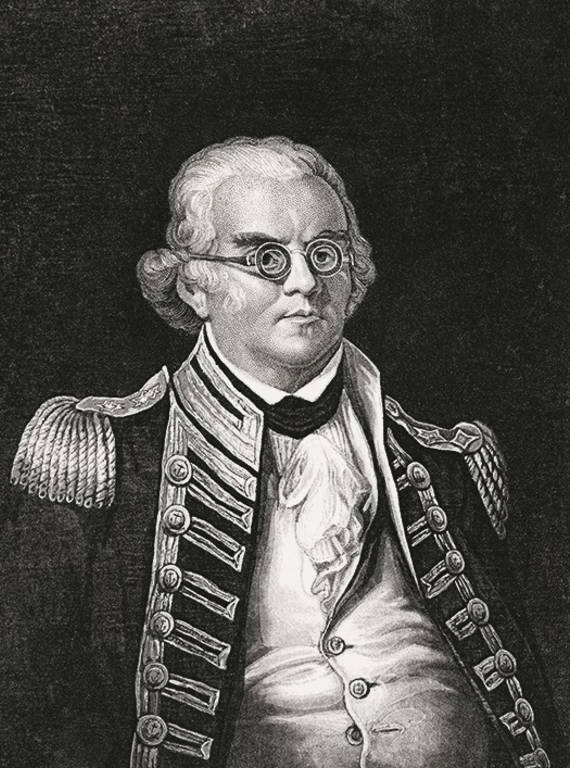

Several campaigns over the past century have attempted to change the name of Mount Rainier, which was named after Peter Rainier, a Royal Navy officer who fought the United States during the Revolutionary War.

© JUSTIN BAILIEShould a natural feature in a national park honor someone who defended slavery and led secessionist states in a war that devastated the country? Is it appropriate for Mount Rainier to bear the name of a British officer who fought the United States? Why keep the Devils Tower name for Wyoming’s famous monolith if it came from an erroneous translation that insults many tribes? Across the country, groups are raising these sorts of questions as they challenge names they deem offensive or inappropriate. These campaigns extend well beyond national parks: Schools, university halls, streets and other landmarks are being renamed to honor overlooked historical figures and remove the taint of unsavory characters. Those leading these efforts say that in the process of cleaning up maps, they’re hoping to make the places themselves more inclusive.

“If history can be read in the names on the land, then it is very partial and very fragmented,” said Lauret Savoy, the author of “Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape” and a member of NPCA’s board. “It would do us all well to see what’s missing.”

NPCA at 100

Changing the name of a mountain, lake or other geographical feature in a national park is a lengthy process, although the first step is easy: Anyone can send a request to the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, which is the authority on the names of natural features — located on public or private land — that appear on federal maps. The board, which is composed of members of various government agencies including the Park Service, conducts extensive research into both the existing and proposed new names, solicits input from various stakeholders including tribes, state bodies and federal agencies, and considers public comment before voting. It can take years to decide on controversial proposals, partly because however improper a name might be to some, locals and visitors often have an emotional attachment to it and resist a change. Opponents cite the cost of replacing signs, brochures and other promotional materials. The more popular the name, the broader the ramifications of a name change become. If Mount Rainier is dropped, what happens to the names of Rainier Beer, Rainier cherries and the Tacoma Rainiers minor league baseball team?

“With a name that has been around for quite some time, the likelihood of getting it changed is not that great,” said Mark Monmonier, a geography professor at Syracuse University who wrote a book about controversial place names.

Peter Rainier

© CHRONICLE/ALAMY STOCK PHOTOSome of the people who oppose name changes view the controversies as part of a larger culture fight. For example, after Minnesota decided to remove “squaw,” a word widely viewed as an offensive reference to a Native American woman, from the state’s maps, reluctant officials in one county proposed replacing Squaw Creek and Squaw Bay with Politically Correct Creek and Politically Correct Bay. (It didn’t pass muster.) Jeff Cruess, a Nevada resident who wants to keep Jeff Davis’ name on the Nevada mountain, said names bestowed long ago shouldn’t be judged by today’s standards. “Washington state was named after George Washington,” he said. “You’re going to change the name of the state because he owned slaves? How far do you take that stuff?” Cruess, who stressed he opposes slavery, said changing the names of places honoring historical figures is equivalent to changing history itself. Others disagree. They note that the place names that are dropped from maps are maintained as variants in official geographical databases and argue that history is preserved in many other ways.

“A name on the map is not history,” Monmonier said. “It’s a name on the map.”

For millennia, tribal peoples living in what is now the United States used place names that were not recorded on paper. Beginning in the era of the first European explorers, government mapmakers retained indigenous names in some form (more than half of U.S. state names originate from Native American languages), but many were eventually dropped and replaced with Western ones, and those that survived were often rife with peculiar transpositions and transcribing errors. Wyoming, for example, is rooted in a Native American word, but one that designated a valley in Pennsylvania. “It was such a dominant white society,” said Gerard Baker, a Mandan-Hidatsa Indian who was the highest-ranking Native American in the Park Service when he retired in 2010. “We never had that political power in those days when they were naming these places.”

The names that appeared on the country’s earliest maps came from a variety of other sources. Some places, such as San Francisco Bay, were named after religious figures; others were meant to honor England’s monarchs (Maryland, the Carolinas). As they moved inland, European explorers and settlers often resorted to descriptive names such as Grand Canyon and Rocky Mountains. The naming of towns and cities was sometimes arbitrary. In “Names on the Land,” George R. Stewart, a midcentury authority on the history of place names, tells of the town of Barre in Vermont whose name was settled by a fistfight. The city of Portland, Oregon, reportedly acquired its name in a coin toss between two settlers — one from Boston and one from Portland, Maine (who evidently won).

By the end of the 19th century, many of the country’s geographical features had been named, but spelling variations were common, and rivers and mountains frequently had more than one name. To bring some order to the nation’s federal maps, President Benjamin Harrison created the U.S. Board on Geographic Names in 1890. The board established a few guiding principles, including the avoidance of possessive forms and a preference for names already used locally and names it considered “euphonious” — or pleasant-sounding.

The board also started handling requests for new names and name changes. There are various reasons to request a name change. Some applicants want to correct erroneous spelling or honor a local personality; other proposals revolve around names that someone has deemed offensive.

The board agreed to automatic changes for derogatory names just twice since its inception. In 1963, under public pressure, the Department of the Interior mandated that an offensive term referring to African Americans be replaced by the word “negro,” and in 1974, the board decided to replace the slur “Jap” with “Japanese.”

Most cases are not that clear-cut. The board has discussed adding “squaw” to its list of unacceptable names, for example, but has refrained from doing so because some tribes don’t consider it disparaging, said Lou Yost, the executive secretary of the board’s Domestic Names Committee. And some names viewed as appropriate replacements decades ago are now considered offensive themselves. A peak on the edge of Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area in California was changed from a name containing the N-word to Negrohead Mountain in the 1960s; in 2009, it was changed again and became Ballard Mountain, in honor of an African American pioneer. Despite the present-day aversion to the term “negro,” such replacements are hardly automatic: Today, hundreds of place names containing the word remain on federal maps.

Native Americans have long taken issue with national park names. In 1915, for example, a delegation of Blackfeet leaders met in Washington, D.C., with soon-to-be Park Service Director Stephen Mather to protest the use of English names in Glacier National Park. But for decades, other issues took precedence. Many national parks were created on land that tribes were forced to vacate, and disputes continued for many decades after the parks’ creation over land claims, hunting rights and proper representation of Native American history, among other issues. For a long time, changing place names was not high on the tribes’ agenda.

That changed in recent decades, and Native American activists and their allies have celebrated several notable successes. Congress changed the name of Custer Battlefield National Monument to Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in 1991. Mount McKinley National Park became Denali National Park in 1980. The mountain itself was also officially rechristened Denali, its Koyukon Athabascan name, but that wasn’t until 2015, when the Department of the Interior issued a secretarial order.

For more than two decades, several tribes have called for changing the name of Devils Tower, which many believe to have originated from the mistranslation of a Native American word for “bear” into “bad god.” (The plural form is a separate issue: The apostrophe in “Devil’s Tower” was erroneously omitted in the 1906 proclamation creating Devils Tower National Monument.) The latest effort is led by Arvol Looking Horse, a spiritual leader of the Lakota Nation, who filed a request to change the name of the butte to Bear Lodge in 2014. Many tribes consider the site sacred, and Looking Horse wrote that the Devils Tower name has provoked “anger and ongoing resentment” among tribal elders, leaders and members.

Starting in the late 1990s, Sen. Mike Enzi of Wyoming has been introducing bills to preserve the name Devils Tower, in part because of the role the site and its current name play in the state’s tourism industry. “He understands the position of Native Americans who would prefer to see the name changed, but he believes much would be lost if the name was changed,” said Rachel Vliem, his spokeswoman, in an email. The Board on Geographic Names refrains from taking action on name proposals under consideration in Congress, so Enzi’s bills effectively stop the process. Park Service officials don’t comment on pending name change requests.

In recent years, national park name campaigns have increasingly focused on renaming geographical features that honor figures with checkered pasts. Yost, the Domestic Names Committee’s executive secretary, said the trend started about five years ago, with the effort to rename Harney Peak in South Dakota. The peak, named after an Army officer who oversaw a massacre of Lakota men, women and children in 1855, was rechristened Black Elk Peak in honor of an Oglala Lakota medicine man from the turn of the century.

Around the time of the Harney Peak controversy, several tribes decided to protest two place names in Yellowstone, and in September 2017, tribal leaders gathered at the park to deliver a letter to a Park Service official demanding that Hayden Valley and Mount Doane be renamed Buffalo Nations Valley and First People’s Mountain, respectively. The tribes also sent a letter to the national board formally petitioning for the name changes.

Chief Stanley Grier of the Piikani Nation hands over a letter to a Yellowstone National Park official in 2017. The letter, which was signed by leaders of several Native American tribes, asks that two landmarks in the park be renamed because they pay tribute to one man the tribes view as a war criminal and another they say was a proponent of genocide.

© BRAD ORSTEDIn 1871, Ferdinand Vandeveer Hayden led a survey of the Yellowstone region that was instrumental in paving the way for the park’s creation the following year, but writing attributed to him extolled white supremacy and advocated for the extermination of nomadic Native Americans unless they settled and embraced the agricultural economy. Right before Gustavus Cheyney Doane participated in two expeditions to the Yellowstone area, he played a leading role in a raid on a camp of Piegan (related to today’s Blackfeet and Piikani Nations) in the Montana Territory that resulted in the deaths of at least 170 people, mostly elderly men, women and children. The band’s chief had been guaranteed protection by the U.S. government. That Doane boasted about his deed when applying for the position of Yellowstone superintendent two decades later (he didn’t get the job) added insult to injury, said Paul Wylie, a Montana historian who wrote a book about the massacre.

Stanley Grier, chief of the Piikani Nation, said every year his people hold a ceremony to honor the massacre victims. “These are relatives of ours,” he said. “They’ve never been forgotten.” He is stunned that Doane’s name has remained on the mountain so long. “There is no honor in massacre,” he said, “so why should we honor those who committed war crimes?”

Jake Fulkerson, the chairman of the Park County Commission, said the proposal caused a “huge uproar” in his Wyoming county, which overlaps with much of Yellowstone. Though he sympathizes with the request, he said he did not receive any calls supporting the name change and that his duty is to respect the will of his constituents. The commission voted to oppose the name changes. “This was not an anti-Native American thing,” he said. “This was just about trying to keep an iconic name in the park.”

Tom Rodgers is undeterred by the opposition. A lobbyist working on behalf of the tribes and a member of the Blackfeet Nation, he vows to keep fighting to honor the memory of his ancestors. “Only after we expunge Capt. Doane’s name can these souls have some peace,” he said.

“We’re facing an awakening and a reckoning in this country when it comes to issues that overlap with racism and historical awareness,” he said. “I totally believe that this is a teachable moment.”

In Boston, Kevin Peterson and his allies have embarked on a similar campaign to change the name of Faneuil Hall, a 277-year-old building that is owned by the city of Boston and is part of Boston National Historical Park. Also known as “the Cradle of Liberty,” the building was funded by Peter Faneuil, a merchant who traded African slaves. The Park Service tells the story of Faneuil’s connections to slavery through tours and the park’s website, but Peterson said that most visitors and Boston residents still ignore Faneuil’s ties to slavery and that many African Americans who are aware of them “feel absolutely humiliated that the name of a slaver adorns a public building.”

Peterson has asked for the city to hold a hearing on the renaming of the building, but so far, the City Council has ignored his request. “If we were to change the name of Faneuil Hall today, 30 years from now, no one would know why we did it,” Mayor Martin J. Walsh said in a statement. “What we should do instead, is figure out a way to acknowledge the history so people understand it.”

Peterson disagrees. He sees the name change debate as a way to get Bostonians to pay attention to the larger problem of racial inequity in Boston, where economic disparity between whites and nonwhites is one of the most pronounced in the nation. “If we can address the issue of slavery in this city, then we can move to having conversations about racial repair,” he said.

Meanwhile, another battle is brewing in the Pacific Northwest. In 1792, explorer George Vancouver named a volcanic peak after his friend Peter Rainier, a Royal Navy officer who had fought the United States in the Revolutionary War. Attempts to change Mount Rainier’s name have come up repeatedly over more than a century.

The name Rainier is not outright offensive, but it feels inadequate and random to Brandon Reynon, a tribal archaeologist for the Puyallup Tribe of Indians. “The guy never saw the peak,” he said. “It would be like me going to Australia, seeing a cool mountain and naming it for my buddy.” The Puyallup and other tribes in the area have a strong connection to the mountain, and Reynon thinks they should oversee the selection of a new name. “In our creation story, she’s our mother,” he said. “She’s where we came from.”

Reynon favors Tacoma (or alternate spellings such as Tahoma and Tacoba), which he said means “place of frozen water” in his language, as the name for the peak in Mount Rainier National Park, but he plans to meet with representatives of other tribes to reach a consensus on a single alternate name to propose. He is confident he can garner the support he needs. “It’s definitely doable,” he said.

Mary Schaff, a member of the Washington State Committee on Geographic Names, is among those who aren’t so sure. She thinks Washingtonians would have a hard time letting go of a name that’s been around for more than 200 years. “It would set up a firestorm,” she said.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Many of these proposed changes will take years to resolve, but in the meantime the effort to rename Jeff Davis Peak has picked up speed. After the initial brouhaha, the Nevada board decided to reach out to local tribes and seek their input. When Warren Graham of the Duckwater Shoshone Tribe received the board’s letter, he decided to consult the tribe’s historian, who directed him to two elderly sisters, members of the Ely Shoshone Tribe of Nevada. The women told Graham their late mother knew the Shoshone name of Jeff Davis Peak — it was called Doso Doyabi, or “white mountain” in Shoshoni. Graham reported back to his tribe’s elders. After discussing the matter, they wrote to the Nevada board, which in January voted unanimously to support renaming Jeff Davis Peak to Doso Doyabi — a decision that still needs to be approved by the national board. (Editor’s note: On June 13, 2019, after National Parks magazine went to press, the U.S. Board on Geographic Names officially changed the name of the peak from Jeff Davis Peak to Doso Doyabi.)

Graham did not initiate the renaming process, but once he got involved, he realized how important it was for his tribe to weigh in. He heard the rationale of those opposing the name change, but he said his effort is not so much about wiping out Davis’ name as it is about restoring a part of his tribe’s heritage. “These places had names before the names they have today,” he said. “What they did to my people was erasing the history that was there before.”

About the author

-

Nicolas Brulliard Senior Editor

Nicolas Brulliard Senior EditorNicolas is a journalist and former geologist who joined NPCA in November 2015. He serves as senior editor of National Parks magazine.