Spring 2019

Growing up with Gettysburg

Over the decades, the park changed. So did I.

I was born and raised in Washington, D.C., and I grew up visiting Park Service Civil War battlefields in the Mid-Atlantic. My parents weren’t “park people,” but they were mindful of a tight family budget and the gasoline shortages that marked the 1970s. And they latched onto places such as Antietam National Battlefield, Gettysburg National Military Park and Harpers Ferry National Historical Park as inexpensive and educational sites less than one tank of gas away from home that they could visit with their only child.

Gettysburg, the site of the largest and bloodiest battle of the American Civil War, was my favorite from the start. Every visit began at the interpretive center, which I recall being a rather nondescript, dimly lit treasure trove of muskets, maps and books plopped at the northern end of Cemetery Ridge. The electric map resided there, and no visit to the battlefield was complete without a viewing of its red and blue lights, which flashed on and off to represent Union and Confederate troop movements over the course of the three-day battle.

After examining the explanatory text and visiting the bookstore, my parents and I would head out to the battle sites: Culp’s Hill, Little Round Top, the Wheatfield. We’d walk over the open, undulating terrain to stand on the hallowed ground where the fate of the nation was decided.

Forever linked to those battlefield visits were the joyous ancillary attractions in the town of Gettysburg. A restaurant, long since closed, served piles of the best fried chicken on the planet, and we ate lunch there after every tour. At a hobby shop on Steinwehr Avenue, discovered by accident, I persuaded my parents to buy me legions of Airfix plastic Civil War figures that were 1/72nd the size of actual soldiers. Once we got home, I would deploy my troops on the floor of my bedroom and refight Pickett’s Charge, the failed Confederate assault on the Union lines that served as the bloody climax of the Battle of Gettysburg.

My study of the tactics and the geography of the Battle of Gettysburg and the American Civil War influenced me deeply and in unexpected ways. Once, during a snowball fight at my school, I led a small contingent of seventh-graders on a flanking maneuver through some undergrowth around a line of burly eighth-graders who were waiting on a snowy field to pulverize us. Imagine a portly African American kid in ill-fitting galoshes channeling Stonewall Jackson at Chancellorsville. We caught the enemy by the flank and rear and drove them ingloriously from the field. It was the best recess I ever had.

As a child, I was fascinated by the war in the naive way a 10-year-old boy from a safe, middle-class home in Washington, D.C., would be. The statues and paintings at Gettysburg showed men (and only men) of valor and courage. Their uniforms were distinctive and often colorful: the baggy red trousers of the Zouaves; the black hats of the fellows from the Iron Brigade; the butternut and gray of the Confederate infantry men, invariably portrayed in serried ranks advancing, as Walt Whitman wrote, “to the muzzles of guns with perfect nonchalance.” The horrors of the Vietnam War still were unfolding daily on the television and in the headlines. Gettysburg was, for me, however, a sanitized version of war that fit neatly into my uncomplicated view of the world.

That began to change as I grew older. Since the 1880s, both the academic and popular culture interpretation of the Civil War had been shifting; over time, the story of the conflict increasingly focused on state’s rights, the virtue of antebellum Southern culture, and the fortitude and infallibility of the Confederate fighting man. This happened at the expense of an honest accounting about the roles race and slavery played in catalyzing the conflict and the active participation of black men and women, free and enslaved, in the prosecution and conclusion of the war. At the very time I started looking to Gettysburg and Antietam to find examples of how the African American experience intertwined with those events, precious little appeared to be on the landscape to feed or sustain my interest and passion.

In 1978, my freshman year in high school, my history class watched black-and-white clips from the 1950s and ’60s in which pro-segregationists waved Confederate flags to intimidate civil rights marchers. I had to come to grips with the fact that the flag Gen. James Longstreet had fought under at Gettysburg had been adopted by white supremacists as a symbol of hate, not heritage.

Then, during my senior year, a history teacher encouraged me to conduct research on the massacre of United States Colored Troops at Fort Pillow in Tennessee. In April 1864, Confederate forces under the command of Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest attacked the fort and overran the Union garrison stationed there. Nearly all the white soldiers who surrendered were taken prisoner while some 300 black Union troops were deliberately killed by Forrest’s men after laying down their arms.

Some argue that Forrest’s men acted without his consent or that the massacre never happened. But Union Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s reaction to news of the massacre was to suspend the practice of paroling and exchanging captured Confederates until the South agreed to treat its black prisoners humanely. The South refused to comply, and prisons in both the North and South, especially at sites such as Andersonville in Georgia, began to bulge with prisoners of war. After my research on Fort Pillow, I was never again able to regard the Confederacy or the Confederate battle flag with neutrality, as I had when I was a child.

As a young adult, my interest in Gettysburg and Civil War history waned. I visited the battlefield less and began to explore other aspects of American history. I still kept my plastic soldiers and once spent the better part of a first (and only) date displaying for an astonished young woman my miniature armies. Once a Civil War geek, always a Civil War geek.

I suppose it was nostalgia that brought me back to Gettysburg one day in my early 30s, and a chance encounter with an interpretive marker that rekindled my love for the park. At the northern end of Cemetery Ridge lies the white house and barn of Abraham Brian. Brian, I discovered during this trip, was a free African American man whose property stood on the ground one mile from where the left flank of the Confederate forces attacking the Union lines during Pickett’s Charge began their assault on July 3, 1863.

I had seen the house during previous visits to the battlefield, but I had never stopped to visit it. Nor had I ever seen or read the interpretive marker next to the structure. When I learned that this house, literally at the center of the park, had been the home of a free black man, his wife and their five children, I had an epiphany. No black troops had fought at Gettysburg, at least not in any formal units. But a black family was directly connected to this battlefield, and their story was being acknowledged and shared by the National Park Service.

I began to wonder what other stories I’d missed on these landscapes, and it appeared that the Park Service had also become curious about the untold stories at its battlefield parks. Slowly but surely, the old, orthodox interpretation of Civil War history was becoming more inclusive, more accurate and, I dare say, more compelling.

A few years later, after I’d started working at NPCA, I had the great fortune to take a tour of Gettysburg in the company of several of the organization’s board members and “Battle Cry of Freedom” author James McPherson. Ranger Terry Latschar led us off the battlefield and into the town of Gettysburg on a tour highlighting the African American history there. We heard about Gettysburg’s role as a major stop on the Underground Railroad and were introduced to characters such as Mag Palm, a powerfully built African American woman and resident of Gettysburg who allegedly beat up a gang of slave catchers who dared one night to try to apprehend her. Our final stop was the Lincoln Cemetery, the segregated burial place for Gettysburg’s black population where among the gravestones is a large marker bearing the names of roughly 30 African American men who fought for the Union during the Civil War.

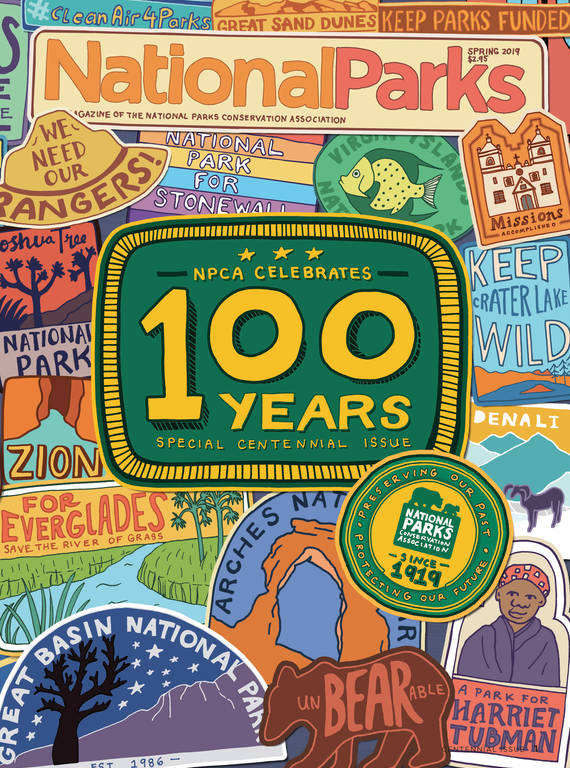

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›This history had always been a part of the Gettysburg experience, but it was just hidden (often) in plain sight. It took leadership from Park Service employees such as Latschar and former chief historian Dwight Pitcaithley and prodding from the likes of McPherson, the late historian James Oliver Horton and former Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. to help reclaim a space for the African American experience in the National Park System’s interpretation of the Civil War. Gettysburg helped lead the way.

These days, 10-year-olds might begin their trips to the battlefield by watching “A New Birth of Freedom,” a video narrated by actor Morgan Freeman that describes the details of the three-day battle and identifies slavery as a root cause of the Civil War. Then, after a stop in the bookshop, these young visitors might take brief hikes on a trail running through the woods toward the battlefield, past Gen. George G. Meade’s headquarters at the Leister House and up the long rise to Cemetery Hill. There, they would spot, among all the cannons, a simple white house and barn, the home of Abraham Brian, a free black man. And they might learn, much earlier than I did, that the history of this country is wonderfully complex and more fully integrated than we’ve been led to believe.

Forty years after I toured this site in a replica Hardee hat and bell-bottoms in colors louder than any Civil War cannon, the battlefield and I have both grown up, and for that I am truly grateful.

About the author

-

Alan Spears Senior Director of Cultural Resources, Government Affairs

Alan Spears Senior Director of Cultural Resources, Government AffairsAlan joined NPCA in 1999 and is currently the Senior Director of Cultural Resources in the Government Affairs department. He serves as NPCA's resident historian and cultural resources expert. Alan is the only staff person to ever be rescued from a tidal marsh by a Park Police helicopter.