Winter 2019

No English? No Problem.

As the number of international visitors to national parks rises, the Park Service is speaking up — in multiple languages.

In the summer of 2017 at Yellowstone National Park, Evan Hubbard, a ranger from rural New Mexico, approached two Chinese women standing by Old Faithful geyser with a miniature poodle.

“We don’t allow animals other than service animals near the geysers,” Hubbard said to the women, a mother and her daughter. One turned to the other and said, in Mandarin, “As soon as he’s gone, we’ll just put the dog in our backpack.”

“That would not be the best course of action,” Hubbard said in Mandarin, much to their surprise.

As international visitation to the U.S. grows, the number of overseas visitors to the parks also has spiked. In 2017, the U.S. welcomed nearly 77 million international visitors, and a significant percentage stopped at national park sites, according to the Department of Commerce. (The National Park Service doesn’t comprehensively track where visitors come from or whether they are foreign.) Brand USA, which promotes the U.S. as a destination to international markets, reported in September that its popular IMAX film, “National Parks Adventure,” is on track to inspire an estimated 170,000 foreign visitors to travel to the U.S.

The Park Service has taken notice. To accommodate foreigners, park staff increasingly are translating websites, videos, trail guides, newspapers and park brochures into multiple languages. At the same time, a growing number of parks are recruiting employees who can speak foreign languages, including Spanish, Mandarin and French. These rangers, along with bilingual and multilingual volunteers, have been tasked with communicating with visitors from afar. (To be sure, the Park Service also is working to engage local community members who are not native English speakers. That ongoing effort includes multilingual communication, partnering with schools and improving regional transit.)

To accommodate the growing number of foreigners, park staff increasingly are translating websites, videos, trail guides, newspapers and park brochures into multiple languages.

NPSIn the past decade, the number of Chinese tourists visiting national parks has grown at an especially fast pace, said Donny Leadbetter, the Park Service’s tourism program manager. “It’s the outbound market driving the travel industry around the world,” he said.

Yellowstone alone sees hundreds of thousands of Chinese visitors each year. In 2016, Judy Knuth Folts, the park’s deputy chief of operations for the Division of Resource Education and Youth Programs, applied for a grant from Yellowstone’s nonprofit partner, Yellowstone Forever, to employ Mandarin-speaking seasonal rangers.

“We want to make sure these visitors have safe visits and help protect our natural and cultural resources,” said Knuth Folts. “Bilingual rangers are excellent liaisons for making this happen.”

The grant enabled Yellowstone to hire several summer rangers, including Hubbard, who has since become a permanent staff member. He wears a sign with Mandarin characters for “I speak Chinese” on his backpack and often hears people say, “Oh, he speaks Chinese!” before approaching him.

Rangers say translating safety messages to foreign visitors is their most important responsibility, whether it’s telling folks not to feed bison or directing them to move away from a canyon rim.

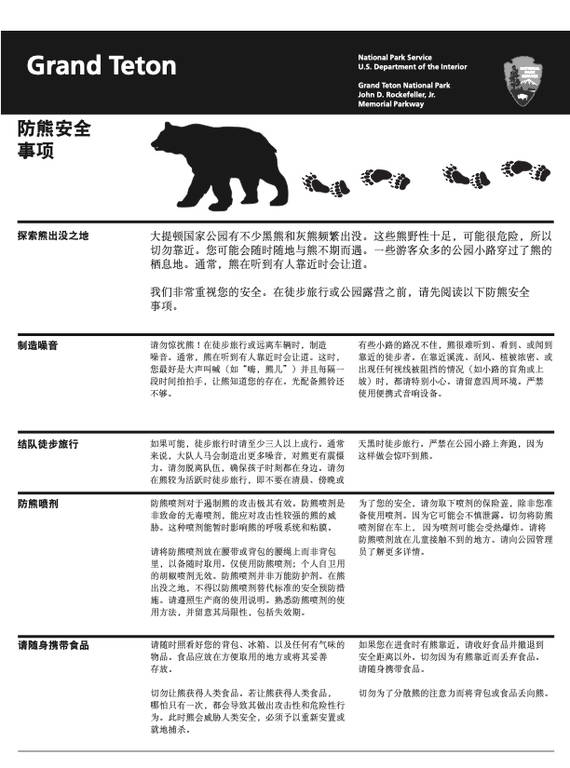

NPSIn 2017, staff at Grand Teton National Park created an internal information sheet, “What to Know about Chinese Culture When Serving Chinese Visitors.” Among the points: Most parks in China don’t have wilderness areas, so Chinese people don’t always understand the inherent risks of backcountry travel; and many only encounter wild animals in shows or zoos, so they may not know that feeding wildlife is dangerous. (The sheet also explains that in China, toilet seats are usually used only at home and are considered unsanitary in public. Recently, Yellowstone and Arches National Park installed squat toilets, which are more typical in China.)

In addition to speaking Mandarin, Hubbard is fluent in Hebrew and Spanish. Other rangers at Yellowstone speak German, French and Polish, and across the country, park staff speak more than a dozen languages. Spanish, which is probably most common, is spoken both at parks near the Mexican border — including Big Bend National Park, Carlsbad Caverns National Park, Saguaro National Park and San Antonio Missions National Historical Park — and at sites in places from Florida to Oregon. St. Croix Island International Historic Site, a small park on the border of Maine and Canada, translates some wall text and exhibit materials into French and has French-speaking rangers to greet visitors from the north, as well as those from France. Everglades National Park schedules a popular volunteer-led tour in German every Wednesday. The National Mall employs rangers fluent in Spanish, Japanese, German, Somali and Mandarin and has volunteers who speak French, Vietnamese and Portuguese.

In general, bilingual rangers say translating safety messages to foreign visitors is their most important responsibility, whether it’s telling folks not to feed bison or directing them to move away from a canyon rim. (Hubbard recently warned a group from Israel to keep their distance from wildlife during the elk rut, or mating season). The rangers also educate visitors about regulations — for instance, that it’s illegal to fly drones in parks or wade in pools at memorials. They explain the ethos of “leave no trace,” and they translate for medical staff and law enforcement.

Many of those messages appear in written materials as well. Grand Teton offers handouts in a half-dozen languages, including a Mandarin sheet on bear safety and an Italian brochure on day hikes. At the gift shop, visitors can purchase the park’s official guidebook in Mandarin. Everglades, where around 60 percent of summer visitors are international, offers brochures in nine languages, including Russian and Japanese.

Park guide Catherine Alvarado Cilfone offers regular National Mall tours in English and Spanish and always has mapas of the park on hand, which she said is the best way for rangers to assist visitors and start informal conversations. She routinely approaches groups of Spanish speakers and asks if she can help: “Les puedo ayudar?” Recently, she met an Argentine woman traveling with her teenage niece and nephew at the World War II Memorial. The teens asked, in Spanish, “Why did the war happen? Why is the memorial so large?”

“I was impressed by the curiosity of these young people,” Cilfone said. “I was able to talk to them informally and explain about World War II in their own language, in a very basic way. Many international visitors come and look at things, and they can’t ask questions. So when I hear anyone speaking Spanish, I make an effort to reach out. The reaction is always so positive, I wish I could speak more languages.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Hubbard, the Yellowstone ranger, has been connecting with people from other countries much of his life, having lived and worked in Spain, Israel and China. “My parents wanted to instill in us an understanding of the incredible diversity of the world,” he said. He’s been struck by the generosity of others around the globe and considers his work reaching out to international visitors a way to give back. “When they’re in some sort of trouble, I can guide them,” he said.

Naturally, some visitors are taken aback when Hubbard starts speaking their language, but the conversations almost always take a friendly turn. In the case of the dog-toting mother and daughter from China, soon they were all chatting away happily. “They asked how I came to learn Chinese and about my time in their country,” said Hubbard. “It turned into a very positive interaction that they’ll probably remember.”

About the author

-

Melanie D.G. Kaplan Author

Melanie D.G. Kaplan AuthorMelanie D.G. Kaplan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer. Her book, "LAB DOG: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research," will be published by Hachette in 2025.