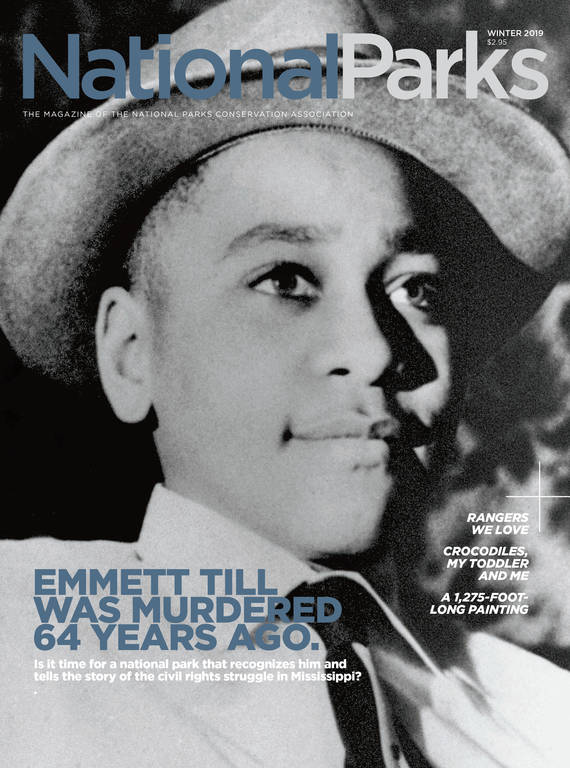

Winter 2019

Valley of Memories

Their land was taken to create Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Each year, their descendants return to reconnect.

Hemmed in by high peaks, Cataloochee is not an easy place to reach. The Cherokee who hunted and fished in the remote valley in North Carolina gave it a name that, according to one translation, means “row upon row,” a possible reference to the rugged mountain ridges. When white settlers established the first homesteads there in the 1840s, they were struck by the wild, isolated beauty. They built frame houses, a church and a school, and tended livestock, farmed vegetables and maintained apple orchards for around 100 years. Even into the 1930s, their communities had no electricity, telephones or local doctor.

In August, around 400 people returned to the valley. The visitors included descendants of the settlers and a handful of seniors who were born on this land, which is now part of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. After driving down a narrow, dirt-and-gravel road, they congregated in Palmer Chapel Methodist Church, where they sang “Amazing Grace,” “Unclouded Day” and other old hymns. Stephen Woody, the master of ceremonies, did roll call, reading out the family names: Caldwell, Hannah, Bennet, Davidson, Sutton, among others. When Palmer was called, nearly half the room stood.

The gathering has been happening for 81 years — with a brief hiatus during World War II — since shortly after the National Park Service bought the land from the residents of Big and Little Cataloochee to create the park, which was authorized in 1926 and established in 1934. Though the event is billed as a “reunion of families,” many call it a homecoming. In past years, as many as 600 people have attended.

Woody remembers visiting the farm of his grandfather, who was one of the last to leave Cataloochee in 1942. “I have a picture of my sister and myself on his horse,” he said. “We would feed the chickens. Dad would fish.” By then, the community had shrunk from a population of around 1,250 in 1900 to a few hundred residents, including the Civilian Conservation Corps members living in the park.

Jonathan Woody, Stephen’s father, began organizing the annual reunion in 1937 and passed on the role to his son in 1975. “I looked at it as a responsibility,” Woody said. “We get a lot of cooperation from the park, and we keep it going.”

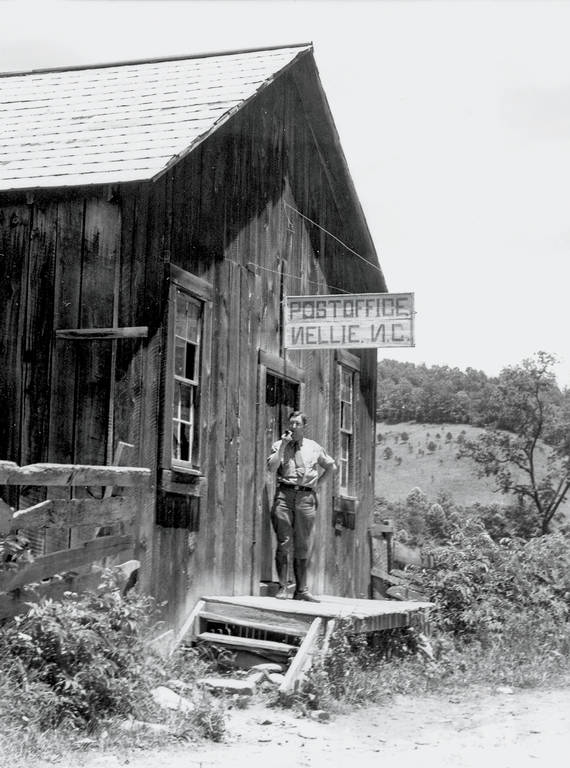

An undated historical photo of the Nellie Post Office and Store in Cataloochee, North Carolina. Descendants of Cataloochee settlers return every year for a reunion in what is now Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVESPark staff carefully maintain and curate the valley’s historic structures, such as Caldwell House and Beech Grove School. To prepare for the gathering in August, they hauled out picnic tables and weeded the cemeteries where the relatives of attendees are buried. A few rangers were on hand to answer questions, and the park’s deputy superintendent spoke at the event.

The relationship between the Park Service and the Cataloochee families hasn’t always been like this: In the early years of the reunion, it was much more strained.

“Lots of people who were forced out were extremely resentful,” said Ronnie Trantham, a guitarist who has led songs at the reunions for around 15 years. “They were not paid enough and didn’t want to leave.” The fact that the park was developed during the Depression made the transition especially hard.

Don Barger, senior director of NPCA’s Southeast Regional Office, explained that unlike most Western parks, which were established on land already owned by the U.S. government, Eastern parks required the acquisition of private land. The states of North Carolina and Tennessee purchased or condemned more than 1,100 tracts to create Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Residents were permitted to stay on as lifetime leaseholders, but the conditions for continuing to live in the park, including paying rent for the land, were onerous, and few economic opportunities existed there. Most relocated. The displacement led to an anti-government animus that still affects some people in the area, Barger said: “My grandfather didn’t like you, my daddy didn’t like you and I don’t like you.”

Early on, the park staff did its best to make inroads. Trantham’s grandfather, Mark Hannah, a Cataloochee native, was hired as one of the first park rangers in the valley. From a talented musical family, Trantham has childhood memories of visiting the ranger station where Hannah lived and singing gospel and bluegrass tunes with his uncles and aunts after dinner. He credits his grandfather with helping to build trust between the park and the displaced community. “Having him there made them feel they could go back and visit and still have a connection they were comfortable with,” he said. “He eased the transition for them. He was a great bridge.”

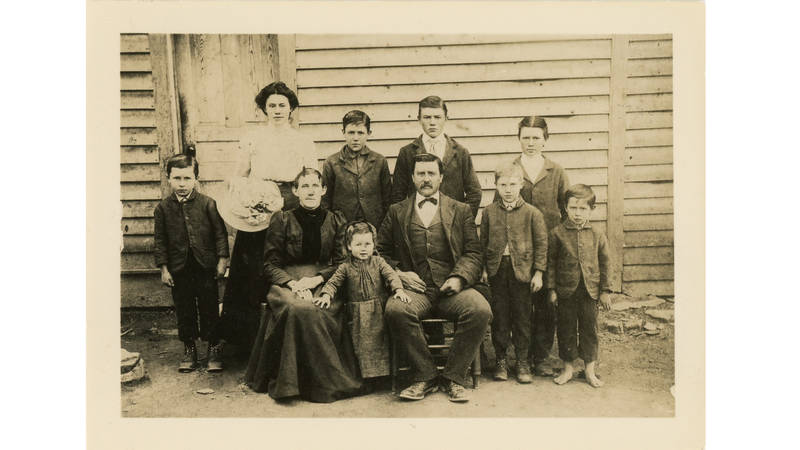

A 1902 photo of Cataloochee resident George H. Caldwell and his family. Before he died in 1928, Caldwell advised his family to sell their home to the Park Service. Caldwell descendants, along with the families of other Cataloochee settlers, return to the valley every year for a reunion.

GREAT SMOKY MOUNTAINS NATIONAL PARK ARCHIVESEven before the national park opened, Cataloochee’s trails and pristine creeks had lured hikers and trout fishermen to the valley. Some residents had capitalized on this, offering tourists food and lodging for a price. Still, savvy as they were, those who left Cataloochee may have found the cultural adjustment jarring. “The times had passed them by,” said Woody. “If the park had never come, there would probably be some people living there today, maybe still without a paved road or electricity.”

Of course, the isolation of Cataloochee has always been part of its allure. “It’s good that it’s hard to get to,” said Lawrence McCleskey, a retired Methodist bishop who spoke at the reunion in 2016. “It maintains its character, which is very rich.”

In 2001, the park worked with local groups to reintroduce a small group of elk, which had been hunted out of the East more than 100 years earlier. As the population has grown, the animals have drawn more traffic to this lesser-known part of one of the country’s most visited national parks. This in turn has opened more eyes to Cataloochee’s past. “Elk bring people into the valley, and the history keeps them there and brings them back,” said Lynda Doucette, a park ranger.

Doucette has attended the last two reunions and was struck by the passion of attendees who are interested in fleshing out their family trees. “They come to connect with family they’ve never met,” she said. “It’s a genealogical drive to find out, ‘Where did I come from?’” In 2017, two brothers from Oregon, who are connected to the Palmer line, flew in for the reunion after discovering their ties to Cataloochee through ancestry.com. They were welcomed with open arms.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›“The huge thing I take away is the fellowship and reconnection to distant family,” said Trantham. “Just knowing you can still reach out and touch those people and interact.”

After the roll call in August, the church bell rang 10 times, once for each person the families had lost that year. Then they ate a potluck lunch: casseroles, deviled eggs, potato salad and homemade desserts such as banana pudding and “stack cake” layered with applesauce.

While families shared food, they mingled and exchanged stories. Gradually small groups of people broke off, wandering to the cemeteries and homeplaces to pay their respects. Later, some played old mountain songs on the porch of the preserved Palmer House.

“It’s bittersweet,” said Woody, “but that’s slowly going away. People now think, ‘Thank goodness the valley was saved.’ It’s a place for everybody.”

About the author

-

Dorian Fox Contributor

Dorian Fox ContributorDorian Fox is a writer and freelance editor whose essays and articles have appeared in various literary journals and other publications. He lives in Boston and teaches creative writing courses through GrubStreet and Pioneer Valley Writers' Workshop. Find more about his work at dorianfox.com.