Fall 2018

Battling History

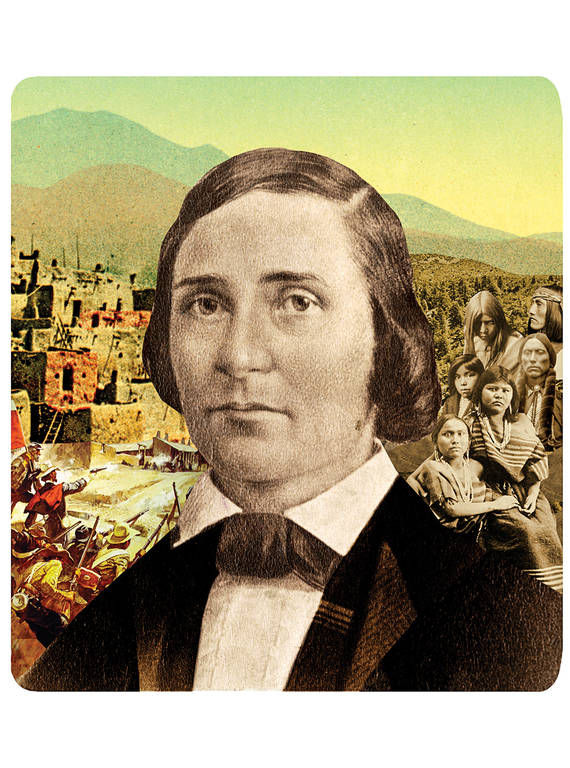

Manuel Chaves was a Civil War hero. He also murdered and enslaved Native Americans. How should we remember him?

Early this spring, a bronze plaque arrived at Pecos National Historical Park, in the junipered folds of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains in northern New Mexico. A slab of sandstone had been placed in the ground to hold it, and a date was picked for its unveiling. Press releases were mailed. Speeches were written.

The plaque’s text, in English and Spanish, commemorated the New Mexico volunteers who fought here in the Battle of Glorieta Pass during the Civil War. Although some historians call it “the Gettysburg of the West,” the battle is little-known. And Lt. Col. Manuel Antonio Chaves, the swashbuckling Hispanic frontiersman who helped seal the Union victory, is not a household name. The small monument aimed to amend that.

But three weeks before the monument’s unveiling, the Associated Press published a story that detailed Chaves’ violent raids against Native Americans. New Mexico Gov. Susana Martinez vetoed a plan to place a bust of Chaves in the capitol’s rotunda, and subsequently, the National Park Service reversed its decision to install the plaque. The park’s superintendent, Karl Cordova, said Chaves is too contentious a character to be honored in a park whose primary draw is the pueblo ruins of the Pecos people.

The Park Service reversed its decision to honor Civil War hero Manuel Chaves after details of his unsavory past become more widely known.

© JOHANNA GOODMAN“It’s our job to protect their ancestral land, and we take that very seriously,” Cordova said. “The last thing we’d want to do is offend their descendants.”

The news stung Andres Romero, the man who began petitioning for the plaque back in 2016. For him, Chaves is a point of ancestral pride — a Hispanic Civil War hero forgotten by an unappreciative Anglo-American majority that has recorded history from its own perspective.

“The whole thing was approved, and then, all of a sudden, they pulled the rug out from under us,” Romero said. “And all to be politically correct.”

Chaves was born 200 years ago in the village of Atrisco, now a suburb of Albuquerque. His family descended from early Spanish conquistadores and raised sheep in New Mexico’s Rio Grande Valley. The region marked Mexico’s northern border and was the territorial nexus of several Native American tribes.

Just 5 feet 7 inches and 140 pounds, Chaves was handsome, steely eyed and soft-voiced. The embattled frontier shaped him into a capable fighter: Fearless under fire, he was a crack shot with his Hawken rifle and a cunning scout. His nickname was El Leoncito — the Little Lion. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, just 13 years after New Mexico became a U.S. territory, Chaves volunteered his services to the Union.

Chaves’ main contribution to the war occurred during the Battle of Glorieta Pass. In March 1862, Confederate troops had captured Santa Fe and Albuquerque and were marching up Apache Canyon in an effort to annex the Southwest before continuing on toward California. At Glorieta Pass, they met Union soldiers and volunteers from Colorado and New Mexico. The three-day battle ended when Chaves guided a group of volunteers on the mesa above the canyon to burn the Confederates’ supply wagons and force their retreat to Texas.

It is not that part of Chaves’ story but his pre–Civil War exploits that lie at the heart of the current dispute. Chaves was born at a time when Spanish settlers were still taking land from Native Americans, and ranchers mounted raids against the Navajo, Ute, Apache and Comanche, stealing children to trade or sell as slaves. According to “The Little Lion of the Southwest,” a 1973 biography by Marc Simmons and the only book written on the man, Chaves first joined these raids at age 16.

Word of his bravery spread, and soon ranchers looked to Chaves to organize attacks to retrieve stolen sheep or horses. Other raids had more nefarious objectives. In 1851, Chaves led 600 men “to pursue the Navajo Nation,” in his words, “to their extermination or complete surrender.” The results of this campaign are unrecorded, but in other attacks Chaves and his men killed dozens of Ute and Apache and stole horses, jewelry, blankets, weapons and slaves. Captured Comanche children became Chaves’ household servants.

According to Romero, who is the vice president of Friends of Pecos National Historical Park, Chaves should be judged within his historical context. “A lot of times you had to fight to save your own life,” he said. “Sure, he went on raids, but so did the Apache, the Comanche and the Navajo.”

Romero first learned about Chaves, one of thousands of Hispanics who served on both sides of the Civil War, when a teacher told him that his high school’s adobe study hall had served as a field hospital during the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Romero started reading about the battle and was surprised that Chaves was not mentioned in official military records. Romero said the omission speaks to the era’s prejudice against New Mexicans, many of whom were Catholic, spoke Spanish and had been Mexican until the U.S. acquired the territory in 1854.

“We’ve been neglected in the history books,” Romero said. “Chaves is the true hero of the Battle of Glorieta Pass. Had it not been for him, we might be living in another country.”

But long before Glorieta Pass was a Civil War battlefield, it was home to the Pecos people, who established a multistory farming and trading pueblo of 2,000 people here around 1400 A.D. Today, most of the 40,000 annual visitors to Pecos National Historical Park come to see these ruins.

So when Cordova, the park superintendent, read about Chaves’ unsavory past, he grew uneasy about honoring him. Two other markers already exist on the battlefield, for the Texas Confederates and Colorado volunteers, and neither mentions any individual. “That’s when I said, ‘Maybe it’s more appropriate if we stay consistent with what’s already out there,’” Cordova said, “making sure that we respect the historical perspective of our native communities as well.”

Cordova has since commissioned a new plaque to honor the New Mexico Civil War volunteers without mentioning names. It will be erected under a juniper, between the Texas and Colorado monuments. The original plaque now stands in the New Mexico National Guard Museum in Santa Fe.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Santa Fe City Historian Andrew Leo Lovato compares the plaque’s controversy to the recent national debate about removing Confederate monuments. “We’re going through a period in the U.S. where we’re re-examining history,” he said. “It gives us an opportunity to look at how attitudes from the past filter into the present.”

Lovato suggests we remember Chaves as a skilled fighter and the byproduct of a violent colonial era. That context helps explain Chaves’ raids, but it doesn’t excuse them. History, and the people whom we celebrate or vilify, are complicated. “It’s easy to put a label on somebody and say they’re good or bad,” Lovato said. “But for most people in American history, whether it’s a president or Kit Carson, there’s more than one way to interpret their lives.”

As for Chaves, he survived the Civil War and all of his campaigns against Native Americans. He became a wealthy man and spent the twilight of his life on his sheep ranch in San Mateo, 130 miles west of the battlefield that notched his place in history. When he died at age 70, blind and frail, with painful, oozing leg wounds, he was buried beneath the church he built. Two musket balls were in his pocket.