Fall 2018

On the Rocks

She went to City of Rocks and Castle Rocks to climb. Then it rained. And hailed. And snowed.

I pressed my body against the cold granite as if we were slow dancing. But I didn’t move.

Eventually, I mustered the courage to lift a foot, carefully raising it a few inches to a ledge no wider than a popsicle stick. With the arch of my foot hugging the rock, I pushed up, positioned my other foot on a similarly insufficient ledge and quickly adjusted my hands to higher spots on the wall, feeling around for something — anything — to grasp. I cupped one hand around a gritty, clamshell-shaped hold. With the other, I reached up, willing my arm to lengthen. The chains anchored into the top of the 40-foot wall — which hold the belay ropes and mark the end of the climb — were within inches, teasing me. Assessing my options, I ran my fingers across the rock by my hips and searched for something that resembled a foothold. Zilch.

Below, Hannah North held onto a rope that would save my life if I lost my footing. Behind me, rigid knobs and spires of gray sprouted up from the land, as though a child had drawn a farm of rocks in a vast array of shapes and sizes. In the distance, snow-covered peaks dotted the horizon, and in the vast quiet, my breathing sounded like a steam engine. I tilted my head back and eyed the chains again. Then I looked at North.

“Can we…” I paused, “just say I touched them?”

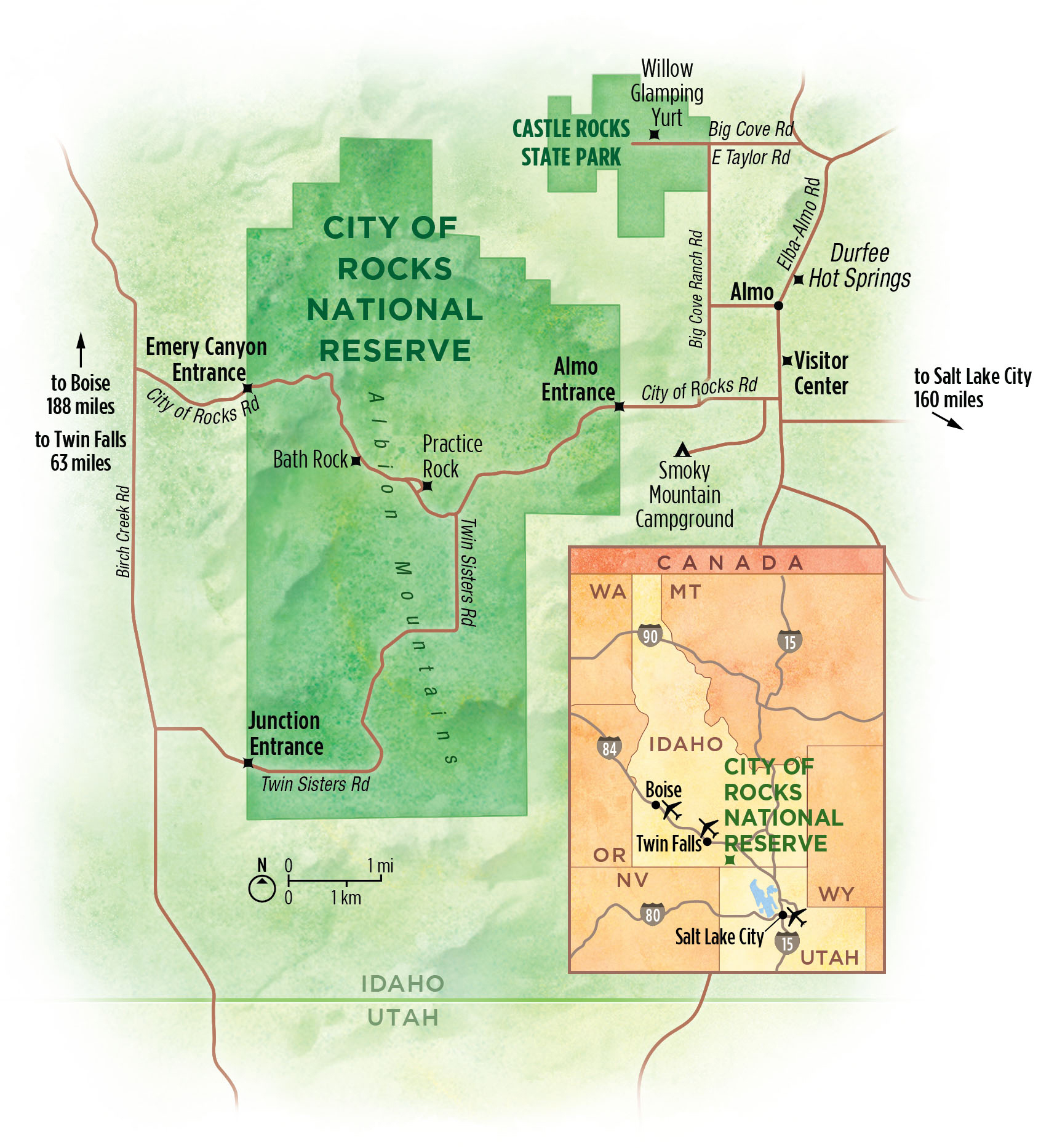

On most days, taxing my fingers means overuse of the Delete key, not digging my digits into granite cracks. But I knew enough about climbing to think I’d like it, so I signed up for a class in the spring, when I visited City of Rocks National Reserve and Castle Rocks State Park in southern Idaho. The parks are also popular destinations for hikers, birders, mountain bikers and horseback riders, and I was particularly excited to be off the grid for several days; locals had told me not to expect cell service. I invited Gaston Lacombe, a photographer who has become a friend after collaborating with me on a handful of articles. We packed our hiking shoes and Gore-Tex (just in case), and met in Boise.

What we hadn’t planned for was a late spring forecast that showed seven shades of gray and images of raindrops morphing into flurries. The day before Gaston and I were set to drive to the parks, I received an email from North, 63, an experienced local climber and park volunteer who had offered to help us climb. “The forecast looks terrible, I’m afraid,” she wrote. “Not only too wet to climb but also too cold.” She asked if we could reschedule, but our trip was sandwiched between firm deadlines and other travel commitments. Plus, North, who is fighting stage 4 lung cancer and doesn’t always feel well enough to climb, was having a good week — another reason to stick to our plan. Things will work out, I assured myself; it can’t possibly rain all weekend.

Tucked into the southern Albion Mountains, the City, as it’s called, and Castle Rocks are located at a “biogeographic crossroads” where three distinct ecosystems intersect, and the parks feature a great diversity of plants and animals ranging from yellow-bellied marmots to moose and even mountain lions. The City is a relatively new national park site, designated only 30 years ago after decades as a National Historic Landmark and National Natural Landmark. The two parks have an unusual partnership: They are both managed by the Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation, and they share a superintendent and visitor center.

The land here has a rich history: It has been home to the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes for centuries, and it’s estimated that around 240,000 pioneers traveling west along the California Trail in the 1800s set up camp at what is today City of Rocks. But the park, with elevations that reach almost 9,000 feet in places, is perhaps best known for its granite, some of the best in the United States for rock climbing.

Climbers began establishing routes at City of Rocks in the 1960s, and in the late 1980s and early ’90s, it was an international hot spot on the climber road trip circuit. The 14,400-acre park was the place for cragging, a fun-in-the-sun, carefree kind of climbing that involves shorter distances, less gear and fewer potential dangers than climbs on bigger cliffs or ice-climbing. Enthusiasts say they like the fact that they don’t have to worry about falling rock or avalanches, for example, and can focus more on choreographing movements up the rock.

As gear became more sophisticated and climbers mastered increasingly difficult climbs, the City came to be seen as what one old-timer described as “passé.” But today, with 600 to nearly 1,000 routes (depending on whom you ask), it’s recognized as a great place for beginner and intermediate climbing. It’s also known as a family-friendly park: Experienced climbers often return to teach their children.

On a Friday afternoon, Gaston and I headed toward the ranching community of Almo, just north of the Utah state line. The scenery was all farmland, and then, suddenly, the granite contours appeared, rising haphazardly across the landscape. At the visitor center, in the middle of town, we ran into Brad Shilling, who retired in 2015 after 20 years as City of Rocks’ lone climbing ranger. I was scheduled to take the park’s introductory climbing class that afternoon, but it had already started raining — and snowing at higher elevations in the park. Since it was too dangerous to climb, Shilling, a compact man with bright blue eyes and white scruff on his cheeks, offered instead to show us around Castle Rocks.

A wagon at the City of Rocks Visitor Center. An estimated 240,000 pioneers traveling west along the California Trail in the 1800s set up camp at what is today City of Rocks.

© GASTON LACOMBEWe stepped out of our vehicles at the park and cinched our hoods against the cold rain. Shilling explained that the parks are home to two types of granite. Most of it is Almo pluton, a 28-million-year-old light gray rock that climbers love because of the way it has eroded to create holds and cracks. “They call it ego granite,” Shilling said, “because it’s so good for your ego.”

A private ranch until 2001, Castle Rocks is still in pristine condition, Shilling said, and it isn’t unusual to find artifacts from Native Americans. He picked up a fragment of obsidian, volcanic glass the size of a corn kernel, which he said had splintered off a prehistoric tool. (The Shoshone-Bannock Tribes still live in the area. Wallace Keck, the superintendent of both parks, later told me about the tension between climbers, who want to scale anything scalable, and Native Americans, who believe the rocks are sacred. Keck has met with tribal representatives to talk about their concerns, an ongoing process. One change he has made is to institute a more selective system for approving permits for new bolts that climbers can clip into.)

SIDE TRIP

A thick blanket of clouds hovered overhead. We walked through a mist of tiny raindrops and snowflakes, circling the park’s namesake rock, a gumdrop-shaped formation with more than 100 climbing routes and 1,200 permanent bolts.

“Brrr, it’s gnarly out there,” Shilling said as we stepped into a small protected rock area. He talked about how the first climber to navigate a new route gets to name it. “First ascents are the thing,” he said, seeming to bounce a little with excitement. “I have close to 100 in Castle Rocks and the City.” He tossed out a few route names he likes: Homeland Insecurity, Patina Turner, Scream Cheese and Just Another Pretty Face.

Without question, rock climbing is an adrenaline sport, he said, but he doesn’t enjoy feeling like he’s truly about to die. The right amount of risk, without a guaranteed outcome, he said, can be exhilarating. “Especially if it’s close, if you have to fight for it,” he added. “When it works out and you survive it, you’re grinning for days.”

Chilled to the bone, Gaston and I hit Durfee Hot Springs — three pools surrounded by a chain-link fence in the center of Almo, a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it kind of a town. It was just what we needed. With steam rising around our faces, we chatted comfortably, and before long, the rain stopped. Sun broke through the clouds, dousing us in warm, radiant sunshine.

Eventually, we drove to our home for the night, a secluded and glampy yurt in Castle Rocks, complete with a giant skylight and electric fireplace. Gaston and I kicked off our boots, switched on the space heaters and popped open locally brewed beer named after a blue-footed booby. I flipped through the guest book as the rain began again with a vengeance. “Inconvenient weather makes great memories and better stories,” one person had written.

Those words were still lingering in my mind when we awoke the next morning. The park looked like a scene from a scary fable: ominous skies sagged over dark, jagged formations. The fog was so thick that Castle Rock — on our front “lawn” — had completely disappeared. The thermometer hovered just above freezing.

Climbing was out, but the birds were chirping vigorously, so Keck led his planned daylong tour for International Migratory Bird Day. Keck is a former climber who grew up in the Ozarks and loves the wide-open spaces, dry air and smell of sagebrush in the West. “It is all about breathing, stretching, freedom and creativity,” he told me.

Keck calls himself an “old school naturalist.” He can talk for hours about the land and can rattle off most of the 400-plus plant, 173 bird and 68 mammal species found in the reserve and Castle Rocks. Before he’d even left the visitor center parking lot that morning, he’d spied a Cassin’s finch, ring-necked pheasant, black-billed magpie, Brewer’s blackbird and common raven.

Our small group of birders caravanned south on a dirt road, briefly stopping every half-mile or so for sightings. Each time we stepped out of our cars into freezing rain, Keck seemed to be straining his senses. “Oooh, hear that?” he asked. “That may be our Brewer’s sparrow.” He pointed out a short-eared owl slowly flapping its wings and a golden eagle, a permanent resident.

After a couple of hours of shaking droplets from our jackets and blasting heat in the car, Gaston and I succumbed to the weather. I told Keck we were going to peel off, but before he acknowledged our departure, he concentrated on a faraway obscure sound. He called out a bird name, and the birders promptly marked it on their checklists. Later that day, while we were talking to some local climbers at the visitor center, he walked in and reported that they’d spotted a grand total of 52 bird species.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

Sunday morning, the air was crisp. Cows mooed outside the yurt, and I drew in the fragrance of wet sagebrush. Gaston and I decided to take advantage of a break in the weather and explore the City. After days of rain, the dirt roads were thick as chocolate frosting, and mud caked our car and pants.

The reserve landscape is dotted with shrubs, grasses and short trees. We scrambled up a large boulder across from Bath Rock (a hub for climbers, where they can read park updates or leave notes for one another on a message board) and looked out over Circle Creek Basin, a giant bowl of granite outcroppings.

Before noon, it was raining yet again, silver-dollar-sized raindrops. When it stopped, we geared up to climb, only to watch another storm roll in. Gaston lamented the dearth of sunlight for his shots, and I wondered if the granite would dry for my climbing class — ever.

That evening, we accepted a movie and dinner invitation to North’s house, which she and her husband, Tom Harper, built on 40 acres adjacent to Castle Rocks. North, still wearing a hat and layers, welcomed us inside, and we gathered in front of the TV on reclining lawn chairs to watch “Dirtbag: The Legend of Fred Beckey,” a documentary about the celebrated climber who died last year at age 94.

Afterward, as we ate spaghetti, hail tapped on the roof and North talked about her own climbing history. The daughter of a marine biologist, she grew up in San Diego and experienced terrible seasickness whenever she was on the water. “All I wanted was to be in a landlocked state,” she told us. She’s now climbed for 33 years, and she and Harper moved here a decade ago after she’d left a management job at HP. She was diagnosed with cancer in 2017. By the time we visited, she’d already lived longer than her doctors expected. They had encouraged her to climb and hike — and she was thankful she’d had another season to do so. “I think the serenity of the outdoors helps provide a personal peacefulness to cope with what’s coming,” she told me later in an email.

Back at the yurt that night, the angry skies cleared and unveiled a flood of stars. Gaston and I stepped onto the wraparound deck. It was our final night there, and the next day was our last chance to climb. We made a plea to Mother Nature for a dry day — we needed just one — before crawling into our beds.

She obliged. As we packed our bags the next morning, we were giddy with excitement over brilliant sun — at last! North picked us up at the visitor center, and we drove together into the City, through the mud, over cattle guards, up to 6,370 feet. “Oh, there’s still lenticular clouds,” she said, pointing. “They usually portend worse weather.” I glanced at Gaston.

We parked at Practice Rock, which looked to me very much like the real thing, and met up with the park’s climbing ranger, Roberta Andruska. The previous day, she had outfitted me with a harness, helmet and climbing shoes. North, ever gentle and patient, showed me how to run her thick nylon rope through my harness and make a knot. Standing at the base of a vertical wall, she instructed me to say, “OK, ready to climb,” and then she responded, “Climb on.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›I took my first step and quickly realized the shoes, with a sticky rubber sole, gave me a superpower of grabbiness. I worked my way up the rock face, slowly finding new holds and ledges, occasionally dipping my fingers into granite pockets filled with icy water. With one foot wedged into a crack and my fingers raw from the cold, I told North I was afraid to lift my foot. I imagined losing my footing and swinging into the granite, shattering bones. “That’s what climbing’s about,” she said, “managing your fear.”

With each slow step and tiny ascent, my heart cheered. I was climbing! I looked out over my shoulder to see Elephant Rock, a popular climbing spot, and the shrubs below. Soon I was nearly 40 feet off the ground, and only inches from the permanent chains at the top of the wall. My chest pounding, I tried to muster the oomph for my next move. But my legs weren’t budging. That’s when I decided I was far enough outside my comfort zone. I rappelled down and set two feet safely on the ground.

About the Photographer

Gaston and I drove out of Almo under puffy cumulus clouds, and within moments, the City’s rocks had disappeared behind us. The sun glowed on snow-covered peaks up ahead and in our wake. Clumps of mud dropped from the car, making thudding sounds.

I thought of what one climber had told me about the desire to do something new and different, to go somewhere no one has gone. Then I remembered Shilling’s description of how exhilarating it was to climb without a guaranteed outcome. Now I understood what he’d meant: I’d felt such a rush on the granite, not knowing if I’d make it up or down the wall in one piece. I grinned, just as he’d said I would, and kept grinning as we drove in silence under sunny skies.

About the author

-

Melanie D.G. Kaplan Author

Melanie D.G. Kaplan AuthorMelanie D.G. Kaplan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer. Her book, "LAB DOG: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research," will be published by Hachette in 2025.