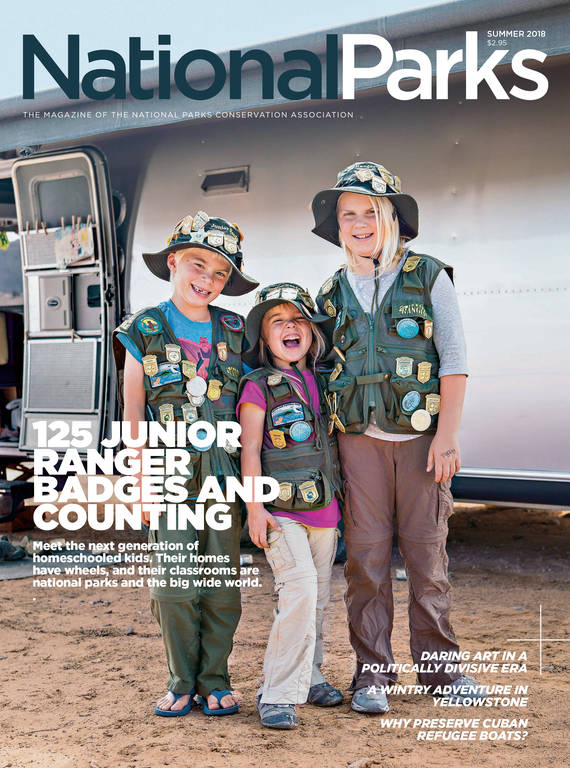

Summer 2018

'Harsh is Truth'

In this divisive political era, is it possible for the Park Service to support contemporary art that grapples with hot-button issues from immigration to climate change?

At these parks, the answer is yes.

A sculpture made of scissors at an old military base. Leaps and turns at a former detention center. Provocative words on the wall of a Colonial meeting house.

This is contemporary art at our national parks.

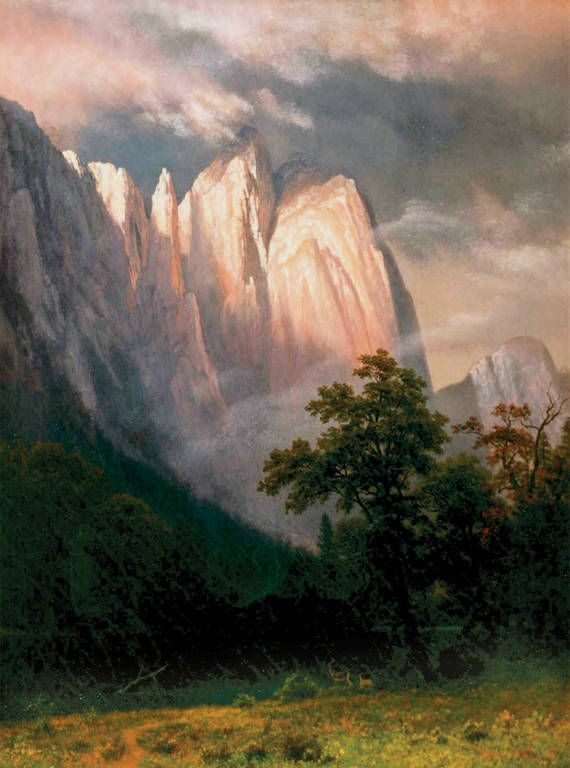

Artists have found inspiration in the country’s parks and wild places since before the U.S. established its first national park in 1872. The depictions of the American West by Hudson River School painters and by photographers such as Carleton Watkins and Ansel Adams helped define the landscape, contributed to the formation and growth of the conservation movement, and played a significant role in the creation of new parks.

The relationship has long been reciprocal: The National Park Service has displayed art in public spaces, commissioned works and cultivated artists. Last year, the agency offered about 60 artist-in-residence programs across the country for painters, sculptors, dancers, potters, videographers, writers, composers and photographers.

Albert Bierstadt’s 1870 oil painting “Cathedral Rocks, Yosemite”

© NPSSome of the artists who have recently won residencies or shown their work in parks use familiar media: watercolors, oil paint, photographs. Others are departing from those sorts of traditional visual practices. They are incorporating surprising materials and art forms, showcasing provocative texts, grappling with weighty topics — from climate change to social justice — and unapologetically presenting their perspectives.

“In the last year, we’ve received so many more requests from artists all over the country to do things in parks,” said Charles Tracy, arts partnership specialist for the Park Service and superintendent of the New England National Scenic Trail. “I think a lot of it may be in response to the political climate. Artists feel like it’s even more important to work in these nationally significant public spaces.”

Some park managers do, too. A growing number understand the value of art in advancing civic dialogue and engagement, Tracy said, and are breaking with tradition and looking beyond plein air painting and landscape photography. Because the Park Service doesn’t have a centralized system of artist residencies or exhibit opportunities, Tracy handles requests on an individual basis, working with funders, artists and parks.

Linda Cook, superintendent at Weir Farm National Historic Site in Connecticut, which is dedicated to American impressionist painting, is the Park Service’s de facto arts superintendent, keeping track of arts programs across the country and promoting arts activities. “Sometimes artists will tackle issues in the parks that don’t fall within our purview,” she said. “They add to the interpretation that parks can provide. We usually engage visitors in words and text, but art is often a far more personal connection.”

From coast to coast and at sites as varied as a historic military park and a remote fire lookout, contemporary art projects at national park sites are touching on political themes, provoking conversations and drawing crowds. Read about five recent works below.

Home Land Security

Several years ago, curator Cheryl Haines traveled to Iran to visit an artist. When she returned and began describing the experience to friends and colleagues, she was struck by the questions they posed. “Were you afraid?” people asked. “Were you in danger?” It seemed to her that the questions stemmed from a fundamental misunderstanding.

“Even the most well-educated and seemingly sophisticated people in our community don’t really have an understanding of different cultures,” said Haines, executive director of the FOR-SITE Foundation, a Bay Area arts nonprofit. It was this sentiment, combined with the U.S. political climate and conversations about barriers between nations and people, that inspired “Home Land Security.” The 2016 exhibition showcased contemporary works by 18 artists and collectives from around the world in former military structures in the Presidio of San Francisco, which is part of Golden Gate National Recreation Area. The works, including sculpture, video, painting and performance art, explored the theme of national security, challenging visitors to consider the physical and psychological borders people create, protect and cross. Haines, who previously had curated a popular show on Alcatraz Island of work by Chinese artist Ai Weiwei, collaborated with the Park Service, the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy and the Presidio Trust on the exhibition.

Haines said the large number of artists and compelling physical space — the military bunkers and other buildings hadn’t previously been open to the public — presented an enormous but interesting curatorial challenge. Each artist was carefully selected, she said, “to illuminate the social and national history of a place and bring it alive with their artistic voice.”

“Home Land Security” opened a few months after the Brexit vote and ran through the U.S. presidential election. In the chilling installation, “2487,” the artist, Luz Maria Sanchez, reads the names of the 2,487 people known to have lost their lives crossing the U.S.-Mexico border between 1993 and 2006. Other works included “Some/One,” a larger-than-life suit of armor that Do Ho Suh crafted out of thousands of military identification tags representing individual soldiers; “Encirclement,” Michele Pred’s sculpture made of objects confiscated by the Transportation Security Administration such as scissors, pocket knives and lighters; and “34,000 Pillows,” which two artists collectively known as Diaz Lewis created in response to the congressional mandate that every day, Immigration and Customs Enforcement fill 34,000 beds in their facilities with immigrant detainees. More than 200 visitors participated in pillow-making.

Artist Do Ho Suh used stainless steel military dog tags to construct “Some/One.” The piece was part of “Home Land Security,” a 2016 exhibit of contemporary works by 18 artists and collectives from around the world.

© ROBERT DIVERS HERRICKBuilding on the success of the exhibit, the Presidio Trust followed up with “Exclusion: The Presidio’s Role in World War II Japanese American Incarceration,” in 2017. Running until next spring, the show opened 75 years after the signing of the 108 civilian exclusion orders, which forced Japanese Americans from areas of the West Coast and held them in incarceration camps during the war. “Exclusion” invites visitors to explore the decisions — ostensibly in the name of national security — that led to these orders, which were signed at the Presidio. One installation shows the names of all 120,000 detainees.

Visitors learn how some Americans spoke against the incarceration, but most were silent. Stations throughout the exhibit encourage people to leave notes about free speech and about the tension between national security and civil liberties. To date, more than 2,000 visitors have left comments, which are on display.

“My grandfather was interned at Manzanar, and through his experience he never stopped fighting for his rights and was a big social justice advocate,” one visitor wrote. “Finding his name on the wall behind me made me feel a responsibility to others who don’t have a voice, and to stand up and make my voice heard.”

Within These Walls

Between 1922 and 1940, three of Lenora Lee’s grandparents immigrated to the United States from China and were processed on Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay. Their experiences — and those of the estimated 170,000 Chinese who, along with many others, were interrogated and detained on the island in the first part of the 20th century — inspired Lee’s most recent work. “Within These Walls,” an immersive, multimedia performance by her company, Lenora Lee Dance, premiered last September at the Angel Island Immigration Station. The show marked an ignominious date: the 135th anniversary of the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, the first federal law preventing a specific ethnic group from immigrating to the U.S.

“I feel like performance is an opportunity to speak,” said Lee, who has been using dance to reflect on the experience of Chinese Americans and other Asian Americans in the San Francisco area for 20 years. “Because of what’s going on politically now, this is an opportunity to engage in that conversation in a creative way, to share from an inside perspective how families were torn apart.”

Now part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area, Angel Island Immigration Station had been slated for demolition until the discovery of 200 Chinese poems — about heartache, longing and freedom — on the walls of the barracks, where some people were detained for months. Visitors reach the island by ferry, then walk or take a shuttle to the station, a journey Lee described as a kind of “pilgrimage” that set the stage for “Within These Walls.” She created the performance to reflect daily life at the station, with 14 dancers and unsuspecting audience members playing the roles of new detainees. When people arrived for each performance, two cast members addressed everyone, including fellow dancers, as though it were 1927. “I’m sure you’ve all been anxiously awaiting your arrival here after your long journey by boat,” said Eric Koziol, who played the inspector.

Audiences traveled through a labyrinth of rooms in the two-story barracks as the dancers moved around them, original music played, and video was projected on the walls. During the 65-minute performance, Lee wore a headset and directed complex, simultaneous scenes in a variety of settings including shower rooms, interrogation areas, dormitories, the office and the beach. The dances are based on real accounts. One, for example, showed an invasive medical examination; another depicted a mess hall riot. Audience members were so drawn into the performances that some reflexively reached out to comfort dancers (some of whom are dealing with their own immigration issues today).

Lee began working with the Park Service to showcase her large-scale dance pieces in 2015, with a performance about veterans called “Fire of Freedom” at Fort Mason, the Golden Gate National Recreation Area headquarters. The next year, she worked with longtime collaborator and composer Francis Wong of San Francisco-based Asian Improv aRts to premiere “Double Victory” at Fort Point National Historic Site in San Francisco. That live performance, commissioned by the Park Service and the Golden Gate National Parks Conservancy, honored Chinese Americans who fought for the U.S. in World War II, despite racist treatment at home.

“Within These Walls,” which ran for two weeks and will return with a sequel in 2019, is Lee’s most complex work to date. After the performances, she talked about the Exclusion Act and connected it to present-day immigration issues. Some audience members came out of the performance crying or angry.

Matthew Spangler, professor of performance studies at San Jose State University, described the performance as moving and beautifully rendered. “And, of course, so timely given the global dialogue around immigration,” he said. “I was there with my 7-year-old son, and the piece made a big impression on him.”

Lee said witnessing some of the scenes can be intense for members of the audience. “People were put in situations where they feel how real these experiences are,” she said. “We can hear the news about immigrant experiences, but to see it in front of you is really powerful.”

A Poet in the Park

Last autumn, Chicana poet and activist Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo, who said a national park residency was on her “writerly bucket list,” became the first participant in the Poets in the Park program at Gettysburg National Military Park.

Poet Xochitl-Julisa Bermejo, the first participant in the Poets in the Park program, was an artist-in-residence at Gettysburg National Military Park in 2017

© LAUREN BARRY FAIRCHILD“In her application, she approached poetry with empathy and feelings that related both to Gettysburg and our current time,” said Tanya Ortega, who heads the National Parks Arts Foundation, the nonprofit that works with the Poetry Foundation to fund the residency. “She wrote about giving a voice to underserved populations.”

Los Angeles-based Bermejo, who calls John Muir a hero and whose first book of poetry focused on borders, said she approached her three-week stint in Pennsylvania as a way to shake off the malaise and shock she was experiencing as a result of the political climate. Encouraged by park staff, she initially planned to explore what she described as “the deep sense of melancholia that has taken over our collective American psyche since the last presidential election.” But she switched course once she began exploring the park. Other visitors looked at her suspiciously, and she saw how her presence — a Mexican American woman walking alone in a park she described as “very white” — was controversial in itself. “My first few days, I was like, ‘What am I doing here, a woman of color in this Civil War place, having to look at Confederate flags and monuments every day?’” she said. “Just being there was its own form of resistance.”

Her discomfort ended up fueling the creative process. She learned that the Mexican-American War was a catalyst for the Civil War, which made her feel connected to this park’s history. Every day, she wrote poetry and walked the battlefield at sunset. The poetry inspired by her residency will explore heroism — especially as it relates to Mexican Americans. “I’m tired of people from my community feeling like outsiders when we have hundreds of years of history here,” she said. “The president likes to say Mexicans are murderers and rapists and drug lords. I’m trying to bring out other images.”

The Edge Effect

At a time when skepticism about climate change is widespread, it’s more important than ever that federal, state, local and tribal agencies gather scientific research and work together, said installation artist Shawn Skabelund. That’s the persistent message in a piece of art that he and photographer Kathleen Brennan created inside a historic fire lookout at New Mexico’s Bandelier National Monument. “The Edge Effect: re-Imagining the East Jemez Landscape,” which was on view from late April through early May, was inspired by the devastating wildfires in the Jemez Mountains over the last 40 years.

Skabelund said climate change, fire suppression, livestock overgrazing (which affects vegetation and alters the path of wildfire) and other human activities have contributed to fires that have drastically changed the landscape and the fabric of the local communities. The artwork featured an abstract map showing the geographic topography and watersheds surrounding the park. Skabelund also created a “vortex form” with 192 pieces of filament. He explained that the fishing line ran from an old circular fire spotter — an instrument used to find the coordinates of a fire — to the ceiling, symbolizing the boundaries that have fractured the landscape.

“Our piece is all about the lines,” Skabelund said, “and a landscape that through time has been demarcated with lines and boundaries. Because of all these boundaries, we no longer have a community that’s concerned with the environment as a whole. Yet fire knows no boundaries.”

Skabelund was an artist-in-residence at Bandelier in 2015, and Jeremy Sweat, the park’s chief of resource management, invited him back after hearing about “Fires of Change,” an exhibition Skabelund curated at the Coconino Center for the Arts in Flagstaff, Arizona. Sweat described the collaboration as a new type of residency — one that uses art to tell stories and to bring more people, including those who aren’t especially science-oriented, into the conversation. “These are their lands, and we manage them on their behalf,” he said. “If the art is a little edgy or makes them a little uncomfortable, that’s a good thing.” (Sweat emphasized that staff selected Skabelund because of his experience working on “Fires of Change” and that hosting the artist was not an endorsement of his political views or other activities.)

Skabelund began displaying his art at national parks in 2012, thanks to an arts residency coordinator at Grand Canyon National Park who took a risk in supporting his overtly political work. He created an installation that addressed uranium mining within the park, an issue he’s even more concerned about today, in light of the current administration’s push to allow uranium mining in areas adjacent to the park.

Skabelund’s views (for example, he’s outraged about President Donald Trump’s decision to shrink Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monuments) sometimes make it difficult to find homes for his art. “I think most parks play it way too safe,” he said. “I find it challenging as a conceptual, political and social artist to find parks accepting of this type of work.”

Talking Truth

The voice of Frederick Douglass rang through a cavernous, nearly 300-year-old meeting house in Boston last year. “If there is no struggle,” he said in a recording of an 1857 speech, “there is no progress.” As the famous abolitionist, orator and social reformer spoke, his words were projected on a two-story wall, and musicians played the marimba and mbira, an African thumb piano.

The performance was part of “Harsh is Truth,” a sound and video projection installation created by Masary Studios, a trio of Boston artists. The name of the work, which explored the definition of “truth,” was inspired by William Lloyd Garrison’s promise to be “harsh as truth” in The Liberator, the abolitionist paper he edited. The artists presented the piece at the Old South Meeting House, a site along the Freedom Trail in Boston National Historical Park.

“We were commissioned to create art and not censor ourselves,” said composer and percussionist Maria Finkelmeier. “We were allowed to be controversial, and that’s very powerful.”

After the white supremacist rally in Charlottesville last summer and counter-protests in Boston, Finkelmeier recorded pedestrians at Boston’s Faneuil Hall talking about how to define truth, and whether there should be a limit to free speech. “It was a difficult project because we were trying to give a lot of people a voice, and it’s a politically charged environment,” she said.

The heart of the installation was a 40-minute piece of original music and site-specific animation that supported the pedestrian recordings and the words of Douglass, Jesse Jackson, and poet and musician Gil Scott-Heron, which were simultaneously performed and projected onto the wall. The location was carefully chosen: The meeting house has served as a space to protest and debate since colonists demonstrated against the tea tax and abolitionists debated slave owners.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Commissioned by “Art on the Trails to Freedom,” the piece was a collaborative effort between the Park Service and New England Foundation for the Arts, a Boston-based arts organization. Charles Tracy, the arts specialist, said he selected Masary because of the group’s experience creating site-specific work and willingness to take risks. “We challenged them to explore contemporary connections with the Freedom Trail’s history of civic discourse, dissent, resistance and revolution,” he said.

Finkelmeier encountered some pushback from pedestrians she interviewed, who questioned the purpose of the recordings, but she feels strongly that art can play a critical role in the debate about truth. “In this administration, where people don’t always converse, using art and human connection is really important,” she said. “We have to keep creating.”

About the author

-

Melanie D.G. Kaplan Author

Melanie D.G. Kaplan AuthorMelanie D.G. Kaplan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer. Her book, "LAB DOG: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research," will be published by Hachette in 2025.