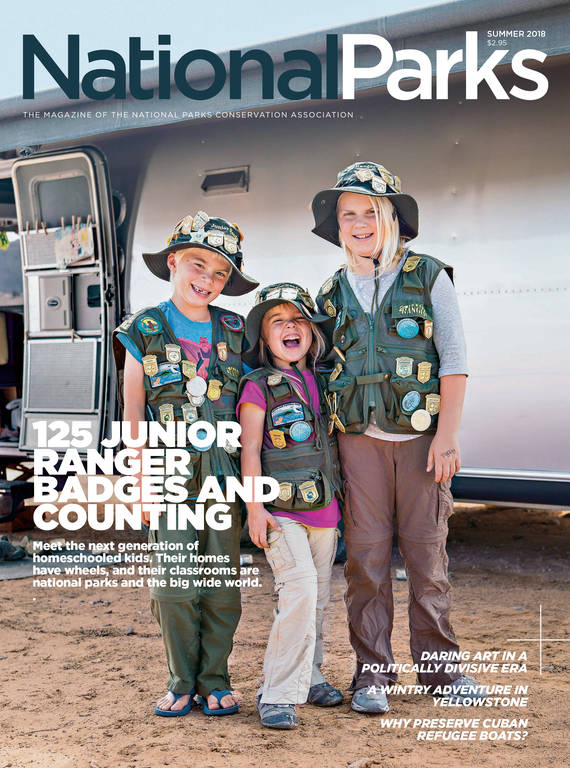

Summer 2018

The Meaning of the Chug

For years, abandoned Cuban refugee boats were considered trash. Now the Park Service and others are preserving the chugs and their stories.

The seven tiny islands of Dry Tortugas National Park, most no more than a swath of white sand, interrupt the 200-mile stretch of open ocean between Havana, Cuba, and mainland Florida. Here in the park, tropical waters are the main draw, but curious visitors can find a different kind of attraction tucked under the archway of a Civil War-era fort: an unassuming piece of aluminum bent into the shape of a boat hull. The vessel, reinforced with fiberglass patches and sealed with hand-smeared tar, helped keep 29 people afloat on a journey from Cuba to the park.

Kelly Clark, the park’s cultural resources specialist, picked up a rough-hewn wooden oar that was resting inside the boat, known as a chug. She noticed a bit of Sharpie scribble on the handle indicating the date it was found, July 4, 2007.

“Hah!” she said. “That’s the dog day!”

She remembers it well. A Cuban chug landed at the campground, which made for “some exciting camping stories” for park patrons. Those aboard the chug included a couple with a dog. When the Coast Guard arrived to transport the refugees off the island, the guardsmen refused to take the pet. The woman wept inconsolably as she and two dozen others boarded a cutter. After the boat pulled away, Clark was left with a small, growling mutt that had escaped its tether.

Clark caught, comforted and fed the dog before sending it by seaplane to Key West. Eventually, she tracked down one of the couple’s relatives, who drove down to pick up the dog and reunite it with its owners.

“I feel like I earned my merit badge that day,” Clark said.

Every chug is full of such stories — of determination, survival, redemption — but for decades, the abandoned boats were disregarded. The vessels, which frequently contained unused oil and gas, were considered a threat to marine navigation and sensitive ecological areas. Often teeming with biohazards, including human waste, they also posed a health risk to park crews and others tasked with disposing of them. The Coast Guard would usually sink or burn the boats, and the parks would dismantle them and haul away the pieces. Some were blown into mangroves, where kayakers and hikers would discover them. The more unusual ones might end up as decoration in someone’s front yard, but even that was rare.

“To lots of folks in the Keys, they were seen as eyesores and treated like day-to-day trash,” said Josh Marano, archaeological technician at Biscayne National Park.

Now that’s starting to change. In recent years, Clark, Marano and other preservationists have begun to save, document, study and exhibit the boats and artifacts found on board. It’s important, they say, because the vessels — and items from medicine to children’s backpacks — offer rare insights into the lives of refugees and the social and economic conditions in Cuba.

“You start to get an idea of how desperate they must have been, to decide to cross with 20 people crammed into a boat the size of a Honda Civic,” Marano said. “Not a lot of people really want to talk about that horrendous journey, but these vessels are now tools for discussion.”

Starting in the 1960s, after the Cuban revolution, thousands began crossing the Florida Strait, seeking an escape from persecution and poverty. At first, a few attempted the journey aboard stolen fishing boats, but most simply took their chances on inner tubes.

“They rode anything that floated,” said Jorge Duany, director of the Cuban Research Institute in Miami. “It was a very treacherous journey. We don’t know how many have died, but it’s thousands.”

At the mercy of the tides, waves and wind, refugees also had to contend with sharks, Portuguese men-of-war and blistering sunshine. Innovation sprang from desperation. People began to add wood planks on top of inner tubes and then attached handmade sails. By the 1990s, many were crossing atop hulls propelled by modified car engines and crafted from blue tarps and expanding foam. One family even set their ’51 Chevy truck afloat by securing it to steel drums. (They eventually made it into the country, but not on that trip.)

Then someone engineered the chug. Named for the noise the small, air-cooled engines made, the vessels were outfitted with handcrafted rudders, an engine near the center, and raised sidewalls to accommodate the weight of many passengers. The hulls, built out of aluminum, copper or fiberglass, were typically 20 to 25 feet long.

“This is pretty peak technological advancement for a chug,” Clark said about the one at Dry Tortugas. “When someone figured out this design, it became the prototype. First one showed up, then within a year or two, it was the standard.”

U.S. immigration policy played a major role in the Cuban exodus and the rise of the chugs. In 1994, after then-President Fidel Castro announced it was no longer a crime for Cubans to flee their country, the number of annual Coast Guard interceptions at sea jumped from a few thousand to more than 37,000. In response to the rafter crisis, the U.S. government revised the Cuban Adjustment Act of 1966, creating a new policy that became known as “wet-foot, dry-foot.” The program more or less granted Cubans who made it to shore the legal right to stay.

By dint of their location, Clark and her colleagues working in Florida’s coastal national parks were the first line of humanitarian aid to thousands who had just survived harrowing days at sea. In one season, hundreds of people landed on and around one 14-acre island in Dry Tortugas.

“There were some days when weather conditions were just right, it’s like, ‘We’d better take a nap now because they’re going to be here,’” Clark said.

During her 15 years at the park, Clark rescued a lot of people, some of whom had misjudged their swimming abilities and ended up a mile or two from land. Most were in need of first aid, food and water, and their clothes often reeked from fumes and were covered in oil. At the remote Tortugas, where it could take more than 24 hours for the Coast Guard to arrive, park staff distributed scrubs, feminine hygiene products, diapers and food that had been provided by a local donor. Though refugees were frequently exhausted, sick or traumatized by the dangerous journey, their spirits were usually high. “Everyone was pretty dang happy and kissing the ground,” Clark said.

Once the refugees made it to shore, the boats quickly turned from vital links to freedom into a cumbersome problem. “We’d often have discussions about where they might fit into the scope of collections,” Clark said. “But this is modern history, and there’s a fine line between hugely important cultural material and abandoned property.”

Eventually, a few years ago, Marano began developing a chug database in partnership with the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary and the Florida Public Archaeology Network. Professional researchers and the general public were invited to submit chug details and photographs. It was an exciting step, but the timing was unfortunate. They unveiled the program at the beginning of 2017, less than a week before the U.S. government rescinded the “wet-foot, dry-foot” policy.

“Literally, it just ended overnight,” Clark said.

Immigration by sea came to an abrupt halt. Chugs were suddenly a finite resource and about to become more so. In March of that year, 31 chugs were destroyed as part of a multi-agency effort to clean up turtle nesting grounds on the Marquesas Keys near Key West. A small group of archaeologists raced ahead of the wrecking boat on foot, snapping pictures and gathering data about each vessel. Six months later, Hurricane Irma wiped out most chugs lingering in the mangroves and many that were on display in public areas.

“I wish in hindsight I would have documented them more thoroughly,” Clark said. “They are definitive of a time that might not exist anymore.”

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Now, the handful of chugs that are still around are particularly valuable. In addition to the chug in Dry Tortugas, park visitors can inspect boats on several islands in Biscayne National Park, and chugs are on display at HistoryMiami Museum, Florida Keys History & Discovery Center, the Key West Tropical Forest & Botanical Garden, and the Mel Fisher Maritime Museum in Key West, where an exhibit of artifacts salvaged from chugs during the last 15 years opened in May.

On a recent afternoon, Corey Malcom, the museum’s archaeology director, pulled out a few items including a handmade snorkel, compass and school papers with English lessons.

“I don’t think anybody can look at these and not be moved,” Malcom said.

Just outside, a small group of curious tourists were looking at the chug that’s on display there. A couple in flip flops and swimsuits sipped from Corona beer bottles while examining the boat from all angles.

“So 24 people were on that boat,” the woman said. “Wow.”

About the author

-

Karuna Eberl Contributor

Karuna Eberl ContributorKaruna Eberl writes about wildlife, history and adventure from the sandbars of the Florida Keys and the high country of Colorado.