Spring 2017

Sandbox in the Sky

High-altitude play at Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve.

The day I set out to climb the tallest sand dune in North America began with a gift from above. As I slithered from my warm sleeping bag before daybreak, a light suddenly shone onto my tent. I unzipped the door, poked my head out, looked left, looked right. Then I peered upward. The heavy clouds had shifted to reveal a brilliant crescent moon.

The campground at Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve in southern Colorado was quiet as I fumbled around, shivering, dressing in what I supposed would be appropriate sand-hiking attire. Wearing gloves, I packed gorp and four bottles of water. A faraway owl cried, “Hoo-hoo!” Outside, the dark dunes stretched out, inviting me closer. The moon lit my path. It was going to be a good day.

When I planned a trip to Colorado for a reprieve from D.C.’s steamy summer weather, I wasn’t picturing spending time in a landscape straight out of Lawrence of Arabia. I imagined mountain hikes and bike rides, rocky terrain and picturesque forests. And that’s what it was like for several weeks last August, when I explored the Rocky Mountains. Then, a friend in Boulder told me about her family’s trip to see the giant sand dunes at a little-known national park just north of the New Mexico border.

TRAVEL ESSENTIALS

“Great Sand Dunes is super fun,” she emailed, attaching a picture of her family jumping down a steep dune, airborne. “It turns adults into kids again. And the sand makes a farting sound when you land — how can you not smile?”

I couldn’t. I packed my car and headed south for some super fun.

Large sand dunes and I share some history. Years ago, I loved hang gliding off dunes in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Then there was the assignment in Qatar, where I went “dune bashing,” as the locals call it, and became so carsick that after only a few ups and downs in our SUV, the driver insisted on turning back.

On the mid-Atlantic coast of the U.S., I — like most beach-goers — am conditioned to stay off the dunes, which are home to many plants and animals and protect the coast from storms. But at the giant sandbox known as Great Sand Dunes, visitors are encouraged to walk, jump, sled, roll and draw as they wish.

“This is one of the few parks where we tell people, ‘Go ahead and write your name in 15-foot letters on the sand dunes,’” said Fred Bunch, the park’s chief of resource management. Rather than remind visitors to stay on the trails, he encourages them to make their own. In his 28 years at the park, Bunch has seen a few wedding proposals written in sand, and then, like the shake of an Etch A Sketch, the next wind erases it all. “Here,” he said, “prints from human activity never last very long.”

It was late afternoon when I first drove toward the park the day before my hike. From a distance, the dunes looked like ant hills next to the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. Jumbo clouds hovered low, grazing mountain peaks as though dangling from the ceiling in a school play.

I stopped by the visitor center for an art class with a young ranger and artist named Graham Oden. In a room with bay windows looking out to the dunes, he handed out watercolor paper, junior ranger pencils and tempera paints.

“The dunes are very amorphous forms,” Oden told us. “Start off with a brush and water, and move it across the paper where you want your crests. Then add pigment.” He painted alongside us, making light brushstrokes with indigo and maroon. I looked out to the dunes and back to my decidedly abstract painting. As a final touch, I sprinkled flecks of yellow on the bottom of the page, for flowers on the high desert valley floor.

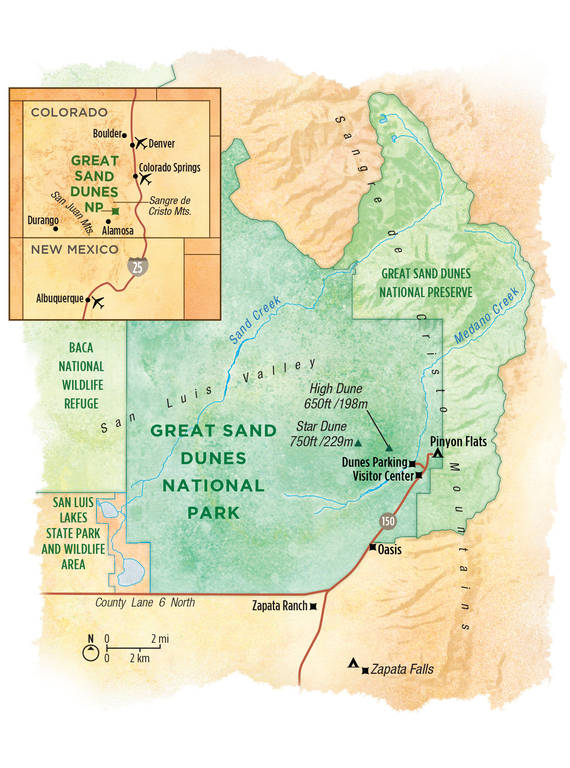

Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve covers about 150,000 acres in all. The dunes account for only a fraction of that, yet they’re the focal point for day visitors and provide an exquisite backdrop for overnighters. After art class, I drove to the park’s campground, which sits 8,200 feet above sea level. I found a corner site with an unobstructed view of the dunes and asked my neighbor, Richard, if he had dune-hiking advice. He suggested climbing the tallest one, Star Dune: “Pick the least steep slope and go!” He told me to carry a walking stick and take rain gear because afternoon storms are common. “Batten down the hatches,” he hollered as I pitched my tent.

The sun set behind the dunes in a purple sky, and I strolled through camp, chatting with a man from Texas who had built his own teardrop trailer. He was inspired to visit the park after seeing a CBS News segment about the park’s acoustics (to which my Boulder friend had charmingly referred), a rare phenomenon called booming sands. In certain conditions, small human- or wind-generated avalanches will make the dunes sing in a very low tone that some compare to the sound of a cello.

The next morning, the crescent moon lit my path out of the campground and toward the dunes. The sky was a dark gray, but the south horizon glowed baby blue. Birds began their morning chatter. Thirty square miles of dunes stretched before me, and I felt like running. I took my first step onto the sand.

Millions of years ago, the San Luis Valley was a lake. Nomadic Paleo-Indians hunted mammoths and prehistoric bison here more than 10,000 years before Spanish explorers arrived. Through the ages, the dunes have swelled and receded in an endless cycle: Erosion of the San Juan and Sangre de Cristo Mountains creates sediment; snowmelt feeds springtime streams, which carry the sand into the valley like a conveyer belt; and opposing winds blow the grains of sand into dunes and push the piles skyward. With every wind storm and flash flood, the landscape changes.

High Dune, which rises to around 700 feet, is the most popular destination in the park, partly because it’s relatively easy to access from the parking lot. Star Dune, with four distinct ridges, is the tallest on the continent, at 750 feet. That was where I was headed.

SIDE TRIP

I walked along the ephemeral Medano Creek. Typically, the water has disappeared by August, but unexpected rains yielded a late summer stream with strands that twisted together like a bundle of nerves. As the water moved over the sand, it babbled softly. A black-billed magpie called from a tree. Wild sunflowers glowed from pockets of sand.

The previous day, a ranger had told me that if I walked to the end of the creek, Star Dune’s distinctive ridges would be in plain sight. They were. I began up a face of the dune, the first footprints of the day.

Walking was exhausting. My calves ached, my feet sank deep and my boots filled with sand. Though I’d been acclimating to the altitude for several weeks, ascending Star Dune took my breath away.

Soon, I righted myself atop the ridgeline, spoiling the perfect pointy edge with each step. Sun rose above the mountains, and I contorted my body to make shadow shapes on adjacent dunes. I was feeling like a kid already! Stopping for a water break, I turned around and sat, stretching out one leg on each side of the ridge. One slope was soft and perfectly flat; the other was firm, rippled by the wind.

Dune climbing is very different from hiking in the mountains. Here, I wasn’t worried about perilous climbs, hard falls, poisonous plants, large animals or losing my bearings. Though I was alone in the wide-open dunefield with no map or compass, I felt invincible. I could see the campsite far below, and the only bad thing that could happen, it seemed, was that I’d drop my camera or notebook, and it would tumble hundreds of feet down the dune.

Two hours and five miles after I left my tent, I summited. The dunes below were now so far away and so small, they reminded me of the pinched edges of pie crust. I sat at the top of the soft mountain, the sound of my breath muted by the wind.

Bounding down the dune made for a quick descent. With each step on the ridge, sand tumbled down the sides in mini-avalanches. I stopped to look at what were probably coyote tracks, and I crouched down to examine a lively circus beetle, one of seven insects found only at this park.

After lunch, I headed to the often overlooked side of Great Sand Dunes — the preserve. This section used to belong to the U.S. Forest Service, and hunting and fishing are permitted there. I hiked a 3.5-mile trail to Mosca Pass, high in the Sangre de Cristos. The partially shaded path follows a stream and winds through forests of aspen and evergreens. I passed purple and red wildflowers, and as I made my way back, I could see a sliver of dunes framed by the colors of the forest.

Early the next morning, I met a British woman, Wendy, in the campground bathroom, and we exchanged bleary-eyed pleasantries. Shortly after, she and her family stood near my campsite to watch the sun rise, and we chatted until the air warmed. I ran into them again in the dunefield, after we’d all rented sleds and hiked up the slopes. At the rental shop just outside the park, a gray-haired man had warned me about sledders reaching speeds of 40 miles an hour. “We say, ‘start off slow,’” he said. He handed me a puck of wax for the bottom of the wooden sled.

Sandboarding is a very popular activity; visitors can rent boards and sleds just outside the park.

© MORGAN HEIMGreat Sand Dunes Superintendent Lisa Carrico told me that 90 percent of the park’s visitors come to play in the creek and on the closest dunes. She grew up in the park in the 1970s; her dad was superintendent of what was then a national monument, and her family lived in a house that today serves as park headquarters. The site officially became a national park and preserve in 2004, but she said otherwise, the place hasn’t changed much.

“It’s Colorado’s high-altitude seashore,” Carrico said. “People set up canopies and bring coolers, dogs play in the creek. In the summer, close your eyes, and it sounds like a beach.”

My first few runs on the sled weren’t pretty — picture doughnuts, tumbling and pockets full of sand. The sporty British family suggested I drag my fingers behind me, like rudders, to stay on a straight path, which made all the difference. They’d made a competition of it, drawing a line where their sleds stopped at the bottom. Wendy quickly surpassed them all, and soon the family moved on to steeper slopes.

The dunes looked like a neighborhood hill on a snow day — kids somersaulted and squealed, grown-ups huffed and puffed as they shuffled back to the top, and tracks crisscrossed the sand. The sand was still cool, so I kicked off my boots and took a few more exhilarating runs, perfecting my technique until I sledded — smugly — straight past the Brits’ lines. On my way back to the parking lot, I walked through the gentle creek, running warm. Kids played with inflatable toys, and dogs splashed. I closed my eyes. Carrico was right.

The San Luis Valley, in many ways, is like a slice of West Texas. Big skies dominate the horizon, John Deeres dot the landscape, mariachi bands play on the car radio and oncoming vehicles are scarce. That afternoon, sand still in my ears from sledding, I drove into the closest town, Alamosa. The farmers market sold large sacks of green chilies and roasted pinon nuts by the bag.

In the evening, my British pals invited me to their campsite. While the kids made s’mores, the parents handed me a microbrew they’d picked up in Durango. “To sand sledding,” I toasted. We agreed it felt wonderful to be physically exhausted and lamented our departure the next day. After going to hear a bluegrass concert at the amphitheater, we said goodbye and talked about meeting at another park one day. We hugged like old friends.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›On my final morning, I tried to stretch out the minutes before leaving. Perhaps one more day of sledding, I thought, would ease the transition back to adult responsibilities. But it wasn’t possible — as soon as the day had begun, I was back on a schedule. While I was mourning the end of what felt like a three-day recess, a pack of coyotes howled. I scrambled out of my tent, hoping to see them in the dunes. Instead, I saw four mule deer walking alongside my campsite. A bunny the size of a grapefruit scampered by and stopped for a moment next to my tent. I tried to hold the coyote song in my head.

Back home, I wrote an email to my mom. Occasionally, when I send her photos, she paints them, so I attached a few shots of the dunes under a pastel sky. In one image, radiant sunflowers stood in the foreground. For a moment, I paused to remember the thrill of speeding down a dune. I’d had sand in my ears and hadn’t even cared.

I wished I were sledding.

I hit send.

About the author

-

Melanie D.G. Kaplan Author

Melanie D.G. Kaplan AuthorMelanie D.G. Kaplan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer. Her book, "LAB DOG: A Beagle and His Human Investigate the Surprising World of Animal Research," will be published by Hachette in 2025.