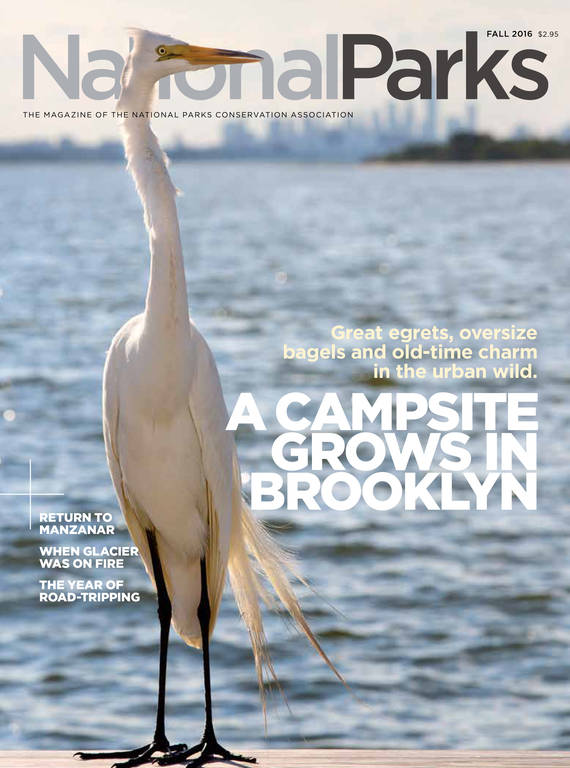

Fall 2016

Fire on the Mountain

A dozen family members gathered in Glacier for a vacation and birthday celebration. Then the perfect storm of fire approached.

For my family, Glacier National Park is a landscape of fire, not ice.

The summer of 2003 is known as “the pinnacle year of fire” in the history of Glacier: 26 fires burned in the park, consuming more than 145,000 acres in three months and breaking all records. It was also the summer the Tempests decided to take a family vacation to celebrate our father’s 70th birthday.

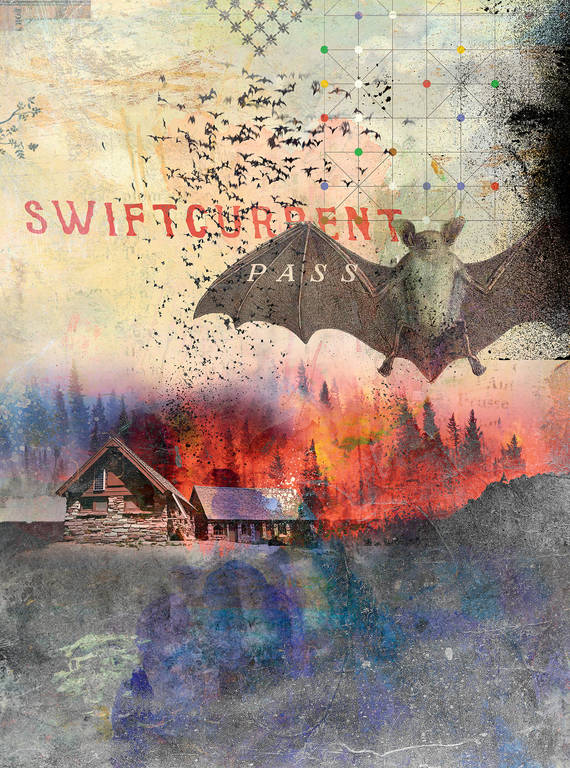

On July 23, 2003, we had reservations for 12 at the Granite Park Chalet for one night. We would stay at the Sperry Chalet our last night and had campsites reserved in between. My father wanted to replicate the backpacking trip we made in 1982, when we hiked 66 miles in six days from the Sperry Chalet to Many Glacier Hotel, stopping at the Granite Park Chalet and crossing Swiftcurrent Pass. This time we were hiking the route in reverse, beginning with the Highline Trail.

More than any other park I know, Glacier embodies the majesty of alpine landscapes — rock castles surrounded by slow-moving rivers of ice and secret lakes the color of turquoise. The hike to Granite Park Chalet, beginning at Logan Pass, is a glory of wildflowers: red paintbrush, sticky geranium, larkspur and flowering stalks of bear’s grass appearing as white globes lighting up the meadows. Our family spaced themselves evenly along the narrow trail beneath the cliff face known as the Garden Wall, with the strongest hikers in front, led by my brother Steve and his wife, Ann. They were followed by their family: Callie and Andrew (newly married), Sara and Diane. My father and his companion, Jan, walked with them; my brother Dan and his wife, Thalo, followed behind. And my husband, Brooke, perhaps the strongest among us, stayed in the rear with me, gathering bones.

There is something soul-satisfying about carrying what you need on your back: water; food; a cook stove; a sleeping bag, pad, and tent; rain gear; a down vest or parka; a hat; gloves; a change of clothes; camp shoes; sunglasses; sunscreen; bug dope; a first-aid kit; a good book and headlamp to read by; a journal; pens; binoculars; camera. And then, with a topo map in hand, you chart your course and walk.

Some of the miles you may talk to your hiking partner, some of the miles you remain quiet, observant to the world embracing you. And there are other miles when your mind not only wanders through a labyrinth of thoughts but climbs the steep hills of obsession, be it love or loss or laments. “Walking it off” is not just a phrase but a form of reverie in the religion of self-reliance, where every mile is registered in the strength of calf muscles.

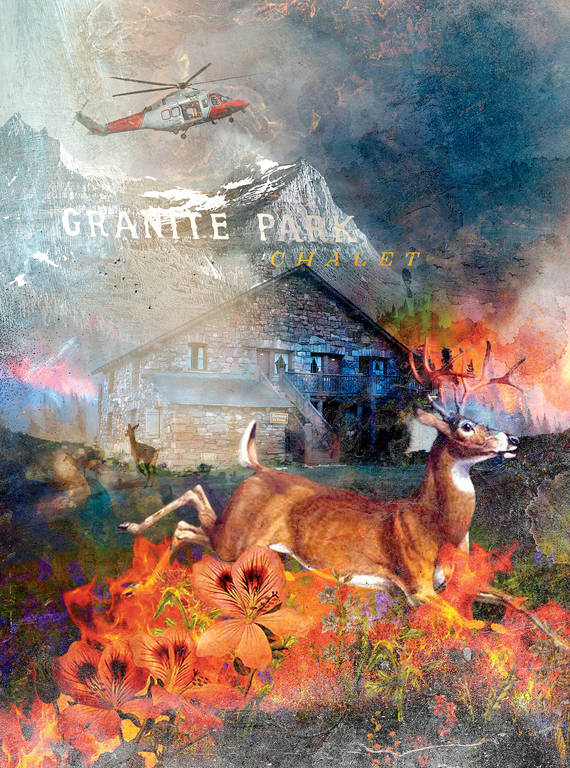

Eight miles later, Granite Park Chalet greeted us with an opaque view of Heavens Peak. Visibility was obscured due to the smoke. The Robert Fire was raging in a far-off drainage that we could see with our binoculars, and the Trapper Fire, with plumes of smoke visible to our naked eyes, had begun earlier in the week. But we had been assured by rangers at Lake McDonald, who carefully checked our itinerary, that the current fires would pose no threat to us.

The Granite Park Chalet is full of alpine charm, a largely stone building that sits at the base of Swiftcurrent Pass with the Grinnell Glacier Overlook just a short, steep hike above. The chalet was built by the Great Northern Railway, between 1914 and 1915 to attract more American tourists with a hut-to-hut trail system like those found in Europe. Of the nine alpine chalets that were built in that era, two remain.

We settled into our designated cabins, furnished with a set of bunk beds that we completed with our sleeping bags. Half the party stayed at the chalet, while the other half hiked up Ahern Pass for a wider view.

My brother Dan and I sat at the picnic table on the chalet’s porch and talked about Jim Harrison’s novella “Legends of the Fall,” set in Montana.

“Do you think fathers and sons are fated to destroy each other?” Dan asked.

“I can’t answer that,” I said, “but I remember hearing a psychologist talk at a conference on boys.

He said, ‘If you want to see a man cry, ask him about his father.’”

Our conversation changed to our mother.

“Do you think we’d all be different if Mother had lived?” Dan asked.

“No question.”

“How?”

And that conversation carried us into the late afternoon.

We all cooked dinner together inside the chalet, having been warned by a large handwritten sign not to touch the shrimp in the freezer. Rumor had it the shrimp had been flown in as a special surprise for First Lady Laura Bush, who, with some of her girlfriends, was arriving at the Granite Park Chalet toward the end of the week.

We watched the sun burn through the smoke and stare at us like the red eye of a demon. And then a blue haze settled on the valley.

That night, I dreamed that a spiral of bats flew out of the forest followed by flames. I woke up anxious.

The next morning, we all noticed the smoke had thickened. As we ate breakfast on the porch of the chalet, fire was on everyone’s mind. Chris Burke, a Park Service employee, appeared anxious as well, his worry heightened by the discovery that the water pump at the chalet was broken. He hiked out to meet a maintenance worker on the trail to get a new part as a safety measure.

About midday on July 24, the flames from the Robert Fire appeared to be coming closer. Dad walked down to the edge of the chasm, a sizable rock-faced cliff that separated us from the forest, to calculate the distance from the fires to the Granite Park Chalet.

“It’s a fair distance,” he said. “But if the winds change, we could be in trouble.”

Just then, a helicopter hovered above us and landed on flat ground. To our surprise, a captain from the smoke jumpers, stationed in Los Angeles, stepped out of the chopper looking like Cool Hand Luke. He had been instructed to stay with us in case the fires escalated. He found a canvas director’s chair, carried it to the top of the knoll, sat down and crossed his legs as he gazed toward the burning horizon, offering us a relaxed image, the epitome of calm.

The other guests at the chalet began to gather, also alarmed by the smoke and the fires that seemed to be advancing. Chris installed the new part needed for the water pump and, with the help of Brooke and Steve, quickly began wetting down the roof of the chalet.

Suddenly a spiral of bats flew out of the forest, just as in my dream. They rose in a black column of wings against the gray sky and then disappeared. My heart began to race. I looked at my watch: 4:30 p.m. The smoke was increasing. The fire was escalating, with spot fires gaining momentum ahead of the blaze, igniting all around us. The captain stood up from his chair. Several deer emerged from the trees and ran behind the chalet. Chris was on his cellphone, talking to the fire lookout. What we didn’t hear from the woman on the other end of his conversation was this: “We can’t calm the beast of Trapper Fire … It looks like it’s making a run for the Granite Park Chalet!”

Chris and the fire captain called us together.

“We seem to be at the center of a perfect storm,” the fire captain said. “The Robert Fire, the Trapper Fire and a new fire unnamed seem to have merged into one crown fire they’re calling the ‘Mountain Man Complex.’ It’s all blown up in the last four hours — and it appears to be heading in our direction.”

“We must prepare ourselves,” Chris added. “Keeping the chalet wet will help, and we need to get rid of whatever could burn on the porch. I could use some help.”

Brooke, Steve and Andrew worked with Chris, throwing the picnic tables and chairs off the porch and down the hillside so there would be nothing burnable next to the stone walls of the historic chalet.

The propane tank nearby was a concern. The winds were picking up dramatically; it was increasingly hard to hear. Chris and the captain passed out particle masks. We stood on the porch bathed in an eerie orange glow, watching in disbelief as firs and pines exploded into flames and pieces of charred bark rained down on us. We could feel the waves of heat as the flames roared from all directions.

Thalo and Dan ran down to their cabin and returned with their backpacks strapped on.

“We’re leaving,” Dan said. “Does anyone want to come with us?”

“I’m gettin’ the hell out of here, before we burn up!” Thalo said, her blue eyes bloodshot and frantic. “I saw what happened to the people who listened to the authorities inside the World Trade Center on September 11th and thought they’d be rescued.”

“You’re better off staying here with the rest of us,” Chris said. “Don’t panic — I don’t think you’ll make it up to Grinnell, the fire’s moving too fast.”

Thalo was already gone.

“I’m going with Thalo,” Dan said. And we watched them walk toward the Grinnell Glacier Overlook, a steep mile and a half away, and disappear into the smoke.

“Do something, John,” the fire captain said to my father.

“He’s a grown man, he’s going to do what he’s going to do,” Dad said. “I can’t stop him.”

“The next person who leaves is under arrest,” the captain said. “Everyone needs to put on their hiking boots and make sure you have your personal ID with you. Go — now — hurry! I want to see everyone inside the chalet as fast as you can get there.”

Flocks of birds were flying helter-skelter into the chaos of the crosswinds. More deer were running out of the woods ahead of the burn. Heat singed my eyelashes. Our eyes were red, and our faces were flushed. Everyone wore masks. I had two extra and put one on each breast for comic relief. Sara and Diane laughed.

Dad, Jan and I rushed down to our cabin to get our necessary gear, fear accelerating with the advancing fire. Chris had run down to the campground and brought other hikers back to the chalet for safety. He mentioned that two former Bureau of Land Management employees from Alaska who had registered at the chalet earlier in the day had disappeared.

Walking briskly back to the chalet with the heat chasing us, I kept looking up the mountain to see whether I could spot Dan and Thalo, but it was consumed in black smoke. The spot fires increased as flames jumped over trees; the wind howled. I turned to see the blaze, now an inferno, racing up the mountain toward us.

Ann was inside the chalet with the girls. Callie and Andrew were standing on the side porch, watching the flames behind us. Brooke and Steve were still working with Chris, getting rid of other flammables and trying to move the propane tank farther away from the building. And then, with long white canvas hoses screwed together, they continued spraying down the roof and porch of the chalet until the very last minute.

“Everybody inside, now!” the fire captain yelled.

A couple had been playing Scrabble. They quickly put away their game. Two women held each other’s hands, crying. A young man in the corner, seeming a bit dazed or drugged, continued playing his guitar, quietly singing, “Come on, baby, light my fire,” until Chris put a hand on his shoulder to get him to stop. I stared out the windows. All I could think of was my brother and his wife in the middle of the firestorm.

Chris made a quick count and turned to the captain. “Two others besides the two that left are unaccounted for. Everyone else is here.”

Thirty-five of us stood in the center of the chalet, most of us coughing. “Okay, everybody, listen up: I want the children sitting in the center. Everyone else sits in a circle around them. The fire is going to reach us in minutes. Stay calm — low to the floor. You’re going to hear a loud roar coming closer and closer. It’s going to get hot, real hot. The windows will shatter. The oxygen’s going to be sucked out of the room — temporarily — and then, hopefully, the fire will quickly move over us and shoot up Swiftcurrent Pass, and we’ll all be just fine. The Park Service knows we’re here. Any questions?” No one said a word. We just sat on the floor, children in the center, holding each other, waiting … some with their eyes closed, praying.

We would later learn that we had been taken for dead by the Park Service. Miraculously, we survived — as did Dan and Thalo, who watched the fire come within 200 feet of the historic Granite Park Chalet, split around us, then rejoin, gather force and roar up Swiftcurrent Pass. The windows didn’t blow out, nor did the oxygen get sucked out of the room. The fire missed us. We were alive.

In Chris’ words: “We could see that the crown fire that had been coming our way had arced around and above us, burning through Swiftcurrent Pass with 200- to-300-foot flame lengths … At sunset, the flames surrounding us lit up the chalet with an orange-pink glow, and spot fires continued to burn above and around.” The two former employees of the BLM who had disappeared reemerged before dark from the latrines, where they had positioned themselves next to the pit toilets, ready to jump in the dark, nasty holes if necessary.

National Parks

You can read this and other stories about history, nature, culture, art, conservation, travel, science and more in National Parks magazine. Your tax-deductible membership donation of $25 or more entitles…

See more ›Our family stayed up all night and, from the porch of the Granite Park Chalet, we watched the fires burn. The intensity of our focus must have been tied to a delusional belief that if we just kept our eyes on the flames, we could keep them at bay. This kind of magical thinking soothed us, even though we all knew it was only the luck of the winds changing direction that had allowed the flames to split and burn around us instead of through us — leaving behind a charred heap of bodies, a circle of ash.

Early the next morning we “escaped” the continuing fires by hiking out the way we had hiked in — single file on the Highline Trail. Only this time, we were led by Chris, with the fire captain bringing up the rear. Three grizzlies walked out with us, slightly below the Garden Wall ledge, having also survived the historic Trapper Fire of 2003.

This essay was excerpted from Terry Tempest Williams’ new book, “The Hour of Land: A Personal Topography of America’s National Parks,” published by Sarah Crichton Books, an imprint of Farrar, Straus and Giroux, LLC. Copyright © 2016 by Terry Tempest Williams. All rights reserved.

About the author

-

Terry Tempest Williams Contributor

Terry Tempest Williams ContributorTERRY TEMPEST WILLIAMS is the award-winning author of 14 books including the environmental literature classic, “Refuge: An Unnatural History of Family and Place.” Her writing has appeared in The New Yorker, The New York Times, Orion Magazine and elsewhere.