Over the summer, NPCA presented its Marjory Stoneman Douglas Award to Japanese American civil rights activist Barbara Takei for her efforts to protect the Tule Lake Unit of WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument. We spoke with this inspiring advocate to learn more about her work and what moves her to preserve this part of American history.

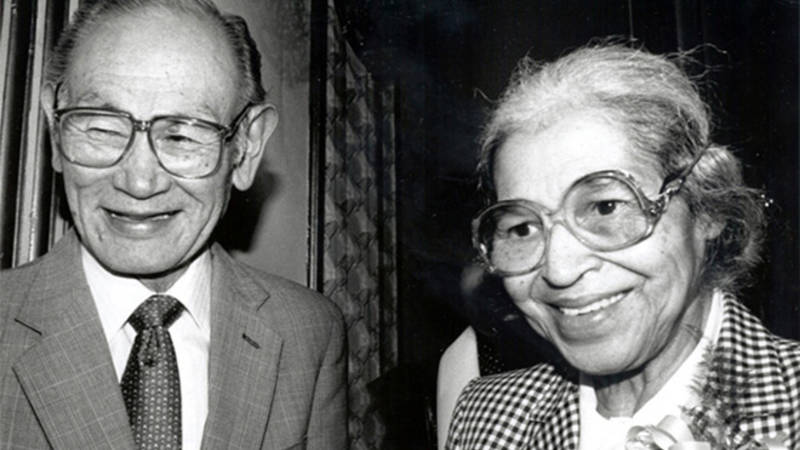

Earlier this summer, I was honored to present NPCA’s Marjory Stoneman Douglas Award to Japanese American civil rights advocate Barbara Takei at the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a national park site she has been working for years to preserve. A board member of the Tule Lake Committee, Takei has been a driving force in gaining recognition for this unit of the WWII Valor in the Pacific National Monument in California. Barbara has worked tirelessly to save historic structures at the site and has successfully advocated for increased federal financial support. Barbara has also helped raise more than $800,000 in funding, matching grants and in-kind donations to protect and help interpret the site’s resources.

A Glimpse into a Dark Part of America’s History

A traveling park lover takes his mom into a windy desert landscape to try to imagine what life was like behind the barbed wire fences of a war relocation center…

See more ›Tule Lake is one of four incarceration camps in the National Park System that the federal government used during World War II to imprison people in the name of military defense. The military overwhelmingly used this power against Japanese and Japanese Americans for the offense of having “foreign enemy ancestry.” Tule Lake had the distinction of being a segregation center where the government incarcerated people it viewed as disloyal troublemakers, who came to be known as “no-nos.”

In 1943, the War Department and the War Relocation Authority developed a “loyalty questionnaire” administered to all adults in its incarceration camps. Two of the questions addressed whether people incarcerated in these camps would be willing to serve on military combat duty and swear allegiance to the United States instead of Japan. People who — for multiple reasons, including protest against the injustice of wartime removal and incarceration — answered no or refused to answer these questions, were segregated to Tule Lake and defamed as “traitors.” Takei has dedicated herself to helping the Park Service share the stories of the stigmatized survivors known as “no-nos.”

On a personal note, I was able to give Takei this award last July as part of an annual pilgrimage that survivors and descendants make to the site each year. It was a heart-stopping experience to see 500 people respond with a sustained standing ovation, recognizing the impact of her achievements. Presenting this award was one of the top highlights of my career at NPCA.

Q: You have been a strong and consistent advocate for the Tule Lake Segregation Center for over a decade. How did you get started and what motivates you to continue your advocacy?

A: Growing up during the civil rights movement, I felt profoundly uncomfortable with the Japanese American stereotype — the one about us being quiet and obedient as we marched into concentration camps without a complaint. It just seemed so unreal that people could be treated so badly and not resist the mistreatment.

It wasn’t until 1999 when I began a book project on Tule Lake that I realized much of the prevailing story of Japanese American passivity was a lie. There was mass, grassroots protest during the incarceration, but government propaganda defined dissenters as disloyal troublemakers and segregated them to Tule Lake, which became a maximum-security prison used to punish the protesters. Tragically, over 12,000 who peacefully resisted the government’s injustice were stigmatized and scorned over most of their lifetimes.

Much of my work in preserving Tule Lake is done to validate and honor those who took enormous risks to resist the injustice, and to ensure this hugely significant civil rights story is included in the Japanese American historical narrative. It’s an incredible history about those who stood up and resisted the injustice of the government. The tragedy is that most of the people who showed great moral and political courage died without ever being acknowledged.

Q: Were your parents among the over 110,000 Japanese American residents imprisoned in camps during the World War II era? Did they talk about their experience?

A: Both my mother’s family and my father’s family lived in California and were incarcerated during WWII. My father was drafted into the Army in February 1941, nearly a year before Pearl Harbor. After the Japanese attack, even though he had already finished his basic training, his weapons were taken away and he was imprisoned in a POW camp in Los Angeles. He was then sent to another Army detention facility in Texas, where he spent almost a year before being sent to Camp Shelby, Mississippi, to join the segregated all-Nisei 522nd Field Artillery Battalion (a unit of the 442 Regimental combat team). Ironically, the 522nd liberated Dachau, while the soldiers’ families were imprisoned in American concentration camps.

The Mysteries of the Panama Hotel

What treasures did Japanese-Americans abandon when they left for internment camps?

See more ›My father rarely talked about his military experience, although a few times he said how traumatic it was to see the prisoners in Dachau, remembering them as “living skeletons” wearing “filthy rags,” and so weak they were “barely able to move.” It’s another story that we don’t hear much about because the Army didn’t want it known that Japanese Americans were liberating European concentration camps while their own families were behind barbed wire, imprisoned in America’s concentration camps.

I learned about the incarceration when I was about 10 years old, reading a book someone had given my parents — “Citizen Number 13660.” The book was sort of like today’s graphic novels, with drawings and text. It was written by a Nisei woman artist named Mine Okubo and seemed so unbelievable when I read it.

When I asked my parents about it, my mother’s explanation was that camp was “fun.” Later on, I learned that it was not uncommon for camp survivors to frame the humiliating experience in a positive way, so they would not put a burden on their children. It wasn’t until I went to college that I started looking for more books on the topic of the Japanese American incarceration, but at the time, in the mid-1960s, there was little to be found. Learning about Tule Lake’s story of dissent came much later. It’s only been in the past decade, since Tule Lake became a national monument and part of NPS that survivors realized their experience didn’t need to be treated as something to be ashamed of.

Q: What are your top concerns right now for the Tule Lake site?

A: We want to get the jail restoration done. Right now, we’ve completed all the architectural planning and the jail is “shovel-ready.” We are hoping the National Park Service will complete the project before most of the survivors of the incarceration are dead.

We want NPS to complete the general management planning process so it can begin work to preserve the Tule Lake site — again, before survivors of the incarceration are gone. As part preserving the site, we also hope that it will be renamed as the Tule Lake National Historic Site to elevate it and make its naming consistent with Manzanar and Minidoka National Historic Sites. As an administrative issue, it should be separated from the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument and become an independent NPS site.

We are very concerned about Modoc County’s plans to build a gigantic fence around the airstrip that sits in the middle of the Tule Lake site, plus plans to widen and lengthen that airstrip. A 3-mile-long, 8-foot-high fence topped with barbed wire, plus a widening and lengthening of the airstrip would destroy the historic fabric and the look and feel of the vast expanse that imprisoned over 18,000 people. We believe the airstrip can and should be moved to another site, rather than destroying the historically significant Tule Lake concentration camp site.

Q: What was the Tule Lake Committee’s role in getting the site designated as unit of the WWII Valor in the Pacific Monument?

A: The Tule Lake Committee began meeting with NPS in 2000, trying to figure out how we could best preserve the historic site. We met with NPS staff, state parks staff, historic preservationists and the California Department of Transportation to explore preservation options for the Tule Lake site, including as a state park, a privately operated historic site or as a national park site. The support of the Pacific West Region of NPS, especially Jon Jarvis who was the regional director, Stephanie Toothman who was regional cultural resources director and David Look who was the NPS cultural resources person who reached out to the Tule Lake Committee, all contributed greatly to examining alternatives to preserve Tule Lake and helped guide its designation, first as a national historic landmark and then as a national monument.

Q: Has the Park Service presence made a big difference?

The Legacy of Fred Korematsu

He fought against his forced imprisonment, all the way to the Supreme Court. Today, the National Park Service helps interpret the dark history behind World War II incarceration camps.

See more ›A: The Park Service presence made a huge difference in Tule Lake’s preservation. In 2006, thanks to the support of the Pacific West Regional office, Tule Lake was designated as a national historic landmark. That designation began to lift the shame and stigma the Japanese American community has, for more than 60 years, associated with Tule Lake, making it more acceptable for someone to admit they were a “no-no” segregated at Tule Lake. People began realizing how government propaganda labeled protest as “troublemaking” and protesters as “disloyal pro-Japan fanatics” as a strategy to demonize dissent. The NPS presence has helped to validate Tule Lake’s story of dissent. It encouraged Japanese Americans who lived through this experience to begin talking about it, and helped their descendants to develop an appreciation for the long-silenced voice of civil rights protest. The Japanese American and larger community is learning that segregation — the unjust division of the community into categories of good and bad, loyal or disloyal — is an important American story about how racism and fear and political opportunism led to the failure of our treasured national values.

Q: Where do you see the Tule Lake Segregation Center 10 years from now?

A: I trust that in 10 years we will have a site comparable to the Manzanar National Historic Site with most of the site preserved and served by a fully staffed visitor center that will interpret the complicated and important story of Tule Lake’s role in punishing dissenters during the wartime incarceration.

I trust that the airport will be moved, relocated in another part of the Tulelake basin that is not historically or culturally significant to the Modoc people, and that the homesteaders will begin to appreciate the national historic site in their midst as an economic and cultural asset that contributes to a revitalized local economy.

Once moved, the relocated Tulelake also needs a new improved runway, security fencing, larger and more secure airplane hangars, and other amenities that will serve the local community.

Q: Can you talk about experiences you and the committee have had with younger generations?

The Art of Gaman

Bearing the seemingly unbearable with patience and dignity.

See more ›A: This past pilgrimage attracted more families and young adults than ever, who are discovering the civil rights piece of the Japanese American narrative at Tule Lake. Several were energized to communicate what they learned in videos, music and even a week-long college conference modeled on the pilgrimage. We are encouraged that the post 9-11 generations are making powerful connections with Tule Lake’s story, recognizing how propaganda and fear destroyed so many lives, and the lie of Japanese American passivity and obedience in response to injustice. At our pilgrimages, we hope to inspire stewardship toward the Tule Lake site, ensuring it will be supported and sustained by future generations.

Q: Is there anything you would like to mention that we have not touched on?

A: Working with NPCA to advance the Tule Lake site has been really wonderful. You’ve been a terrific partner, and we thank you for being with us on this journey to preserve one of America’s special places.

Stay On Top of News

Want more great national park stories and news? Join our email list and get them delivered to your inbox.

About the author

-

Ron Sundergill Former Senior Regional Director

Ron Sundergill Former Senior Regional DirectorRon joined NPCA in 2005. He is the Senior Regional Director for the Pacific office, overseeing the work of the regional office and its four field offices.

-

General

-

- NPCA Region:

- Pacific

-

Issues